Edwards' syndrome

Definition

Edwards' syndrome is caused by an extra (third) copy of chromosome 18. The extra chromosome is lethal for most babies born with this condition. It causes major physical abnormalities and severe mental retardation . Very few children afflicted with this syndrome survive beyond the first year.

Description

Edwards' syndrome is associated with the presence of a third copy of chromosome number 18. Humans normally have 23 pairs of chromosomes. Chromosomes are numbered 1–22, and the 23rd pair is composed of the sex chromosomes, X and Y. A person inherits one set of 23 chromosomes from each parent. Occasionally, a genetic error occurs during egg or sperm cell formation. A child conceived with such an egg or sperm cell may inherit an incorrect number of chromosomes. In the case of Edwards' syndrome, the child inherits three (trisomy), rather than two, copies of chromosome 18. Ninety-five percent of the children are full trisomies, 2 percent are due to translocations, where only part of an extra chromosome is present (this may be hereditary), while 3 percent are mosaic trisomies, where the extra chromosome is present in some but not all of the cells.

Edwards' syndrome is usually fatal, with most babies dying before birth. Of those who do make it to birth, 20–30 percent die within one month. However, a small number of babies (less than 10 percent) live at least one year.

Edwards' syndrome is also referred to as trisomy 18, trisomy E, and trisomy 16–18. It is the second most common trisomy, after trisomy 21 ( Down syndrome ).

Demographics

Edwards' syndrome occurs in approximately one in every 5,000 live births and one in every 5,000 stillborn births; it affects girls more often than boys. Women older than their early thirties have a greater risk of conceiving a child with Edwards' syndrome, but it can also occur with younger mothers.

Causes and symptoms

Most children born with Edwards' syndrome appear weak and fragile, and they are often underweight. The head is unusually small and the back of the head is prominent. The ears are malformed and low-set, and the mouth and jaw are small (micrognathia). The baby may also have a cleft lip or cleft palate . Frequently, the hands are clenched into fists, and the index finger overlaps the other fingers. The child may have clubfeet, and toes may be webbed or fused.

Numerous problems involving the internal organs may be present. Abnormalities often occur in the lungs and diaphragm (the muscle that controls breathing), and blood vessel malformations are common. Various types of congenital heart disease , including ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septic defect (ASD), or PDA ( patent ductus arteriosus ), may be present. The child may have an umbilical or inguinal hernia , malformed kidneys, and abnormalities of the urogenital system, including undescended testicles in a male child (cryptochordism).

When to call the doctor

A child with Edwards' syndrome is likely to have many medical and development needs. Parents should develop good working relationships with their doctor, other specialists, and therapists, and should consult them as needed.

If a woman gives birth to a child with Edwards' syndrome and plans to have another child, a doctor as well as a genetic counselor should be consulted so that prenatal screening and genetic counseling can be conducted.

Diagnosis

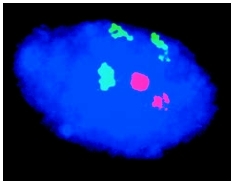

Edwards' syndrome at birth may be diagnosed by the physical abnormalities characteristic to the syndrome. Physical examination of the infant may show arched type finger print patterns, while x rays may reveal a short breast bone (sternum). Definitive diagnosis is achieved through karyotyping, which involves drawing the baby's blood for a microscopic examination of the chromosomes. Using special stains and microscopy, individual chromosomes are identified, and the presence of an extra chromosome 18 is revealed.

Edwards' syndrome can be detected before birth. If a pregnant woman is older than 35, has a family history of genetic abnormalities, has previously conceived a child with a genetic abnormality, or has suffered earlier miscarriages, she may undergo tests to determine whether her child carries genetic abnormalities. Potential tests include maternal serum alpha-fetal protein analysis or screening, ultrasonography, amniocentesis , and chorionic villus sampling.

In addition, a pregnant woman carrying a child with Edwards' syndrome may have an unusually large uterus during pregnancy, due to the presence of extra amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios). An unusually small placenta may be noted during the birth of the child.

Treatment

There is no cure for Edwards' syndrome. Since babies with Edwards' syndrome frequently have major physical abnormalities, doctors and parents face difficult choices regarding treatment. Abnormalities can be treated to a certain degree with surgery, but extreme invasive procedures may not be in the best interests of an infant whose lifespan is measured in days or weeks. Medical therapy often consists of supportive care with the goal of making the infant comfortable, rather than prolonging life.

However, 5–10 percent of children with Edwards' syndrome do survive past the first year of life, and require appropriate treatment for the many chronic effects associated with the syndrome. Problems with muscle tone and nervous system abnormalities will affect the development of motor skills, possibly resulting in scoliosis (curvature of the spine) and esotropia (crossed eyes). Surgical interventions may be limited by child's cardiac health.

Constipation due to poor abdominal muscle tone is often a life-long problem for babies and children with Edwards' syndrome, resulting in fretfulness, discomfort, and feeding problems. Anti-gas medication, special milk formulas, stool softener medicines, laxatives , and suppositories are all possible treatments that the doctor may recommend to ease the discomfort of gas in the bowels or constipation. An enema should not given to the baby or child because it can deplete electrolytes and alter body fluid composition.

Children with Edwards' syndrome will exhibit severe developmental delays, but with early intervention through special education and therapy programs, they can attain some developmental milestones.

Children with Edwards' syndrome appear to have increased risk of developing a Wilms' tumor , a cancer of the kidney that primarily affects children. Therefore, it is recommended that older infants and children with Edwards' syndrome have a routine ultrasound of the abdominal cavity.

Other illnesses that may affect a child with Edwards' syndrome and that may require treatment include congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension , elevated blood pressure, apnea episodes, pneumonias, sinus infections, seizures, urinary tract infections, ear infections, and eye infections. Other abnormalities that may require consideration of medical or surgical intervention include club foot, facial clefts, spina bifida , and hydrocephalus .

Nutritional concerns

Babies with Edwards' syndrome generally have feeding problems related to difficulties in coordination of breathing, sucking, and swallowing. Many have a weak suck and uncoordinated swallow resulting in choking and sometimes vomiting . Gastroesophageal reflux disease , or GERD (the upward movement of small amounts of stomach contents to the esophagus or throat), aspiration (inhalation or trickle of fluids into the lungs), and oral facial clefts may also contribute to feeding difficulties. The baby should be referred to a feeding specialist to help with feeding problems. The specialist can show the parents how to position the baby's head up, in good body alignment, because a baby with Edwards' syndrome may have hyperextension of the head. This is a common condition that occurs before the baby has developed head control. It results in the elongation of throat muscles, making swallowing more difficult. Because of feeding difficulties, many babies with Edwards' syndrome are fed through a tube inserted through the nose or mouth, down through the esophagus, and into the stomach. Some babies eventually progress to bottle or breastfeeding, while others have a gastrostomy (G-tube) placed abdominally to prevent the trauma of tube insertion. Some children are fed both orally and through the tube.

The baby should be fed with pre-softened preemie nipples and given small amounts frequently. To help prevent reflux, the baby's head should be elevated about 30 degrees or more during feeding and for one to two hours after a feeding. If tolerated, high calories formulas or supplements may be fed to help the baby gain weight.

Prognosis

Most children born with Edwards' syndrome die within their first year of life. The average lifespan is less than two months for 50 percent of the children, and 90–95 percent die before their first birthday. The 5–10 percent of children who survive their first year have severe developmental disabilities. They need support to walk, and learning is limited. Verbal communication is also limited, but they can respond to comforting and can learn to recognize, smile, and interact with caregivers and others, and acquire such skills as rolling over and self-feeding. They will have many physical abnormalities that require constant care as doctors and parents work together to prevent and treat various problems.

Prevention

Most cases of Edwards' syndrome are not hereditary and cannot be prevented. However, parents who have had a child with Edwards' syndrome are at increased risk of having another child with the syndrome.

Parental concerns

Following the birth of a child with Edwards' syndrome, families may wish to seek counseling regarding the effects on relationships within the family. Many people respond with guilt, fear , or blame when a genetic disorder is manifested within a family. Support groups are good sources of information about Edwards' syndrome and can offer emotional and psychological support.

KEY TERMS

Amniocentesis —A procedure performed at 16-18 weeks of pregnancy in which a needle is inserted through a woman's abdomen into her uterus to draw out a small sample of the amniotic fluid from around the baby for analysis. Either the fluid itself or cells from the fluid can be used for a variety of tests to obtain information about genetic disorders and other medical conditions in the fetus.

Atrial septal defect —An opening between the right and left atria (upper chambers) of the heart.

Chorionic villus sampling —A procedure performed at 10 to 12 weeks of pregnancy in which a needle is inserted either through the mother's vagina or abdominal wall into the placenta to withdraw a small amount of chorionic membrane from around the early embryo. The amniotic fluid can be examined for signs of chromosome abnormalities or other genetic diseases.

Chromosome —A microscopic thread-like structure found within each cell of the human body and consisting of a complex of proteins and DNA. Humans have 46 chromosomes arranged into 23 pairs. Chromosomes contain the genetic information necessary to direct the development and functioning of all cells and systems in the body. They pass on hereditary traits from parents to child (like eye color) and determine whether the child will be male or female.

Karyotyping —A laboratory test used to study an individual's chromosome make-up. Chromosomes are separated from cells, stained, and arranged in order from largest to smallest so that their number and structure can be studied under a microscope.

Maternal serum analyte screening —A medical procedure in which a pregnant woman's blood is drawn and analyzed for the levels of certain hormones and proteins. These levels can indicate whether there may be an abnormality in the unborn child. This test is not a definitive indicator of a problem and is followed by more specific testing such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling.

Patent ductus arteriosus —A congenital defect in which the temporary blood vessel connecting the left pulmonary artery to the aorta in the fetus doesn't close after birth.

Trisomy —An abnormal condition where three copies of one chromosome are present in the cells of an individual's body instead of two, the normal number.

Ultrasonography —A medical test in which sound waves are directed against internal structures in the body. As sound waves bounce off the internal structure, they create an image on a video screen. Ultrasonography is often used to diagnose fetal abnormalities, gallstones, heart defects, and tumors. Also called ultrasound imaging.

Ventricular septal defect —An opening between the right and left ventricles of the heart.

For those families whose child does survive the first weeks of life, the doctor should review with the parents the expected clinical course of the condition, and prepare a management plan for use when the child goes home. Each case must be considered on an individual basis, and the doctor should acknowledge the personal feelings of the parents, as well as the individual circumstances of each child. The theme of "best interest of the child" helps

See also Atrial septal defect ; Congenital heart disease .

Resources

BOOKS

Barnes, Ann M., and John C. Carey. Care of the Infant and Child with Trisomy 18 and 13: Medical Problems, Reported Treatments, and Milestones. Omaha, NE: Munroes-Meyer Institute for Genetics and Rehabilitation, 2000.

Stenson, Carol M., et al. Trisomy 18: A Guidebook for Families. Omaha, NE: Munroes-Meyer Institute for Genetics and Rehabilitation, 2000.

ORGANIZATIONS

Chromosome 18 Registry & Research Society. 7715 Oakridge Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229. (210) 657-4968. Web site: http://www.chromosome18.org.

Support Organization for Trisomy 18, 13, and Related Disorders (SOFT). 2982 South Union St., Rochester, NY 14624. (800) 716-7638. Web site: http://www.trisomy.org.

WEB SITES

Trisomy 18 Support: Families Caring for Families. Available online at: http://www.trisomy18support.org.

Judith Sims

Julia Barrett