Mental retardation

Definition

Mental retardation is a developmental disability that first appears in children under the age of 18. It is defined as an intellectual functioning level (as measured by standard tests for intelligence quotient) that is well below average and significant limitations in daily living skills (adaptive functioning).

Description

According to statistics made available by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the 1990s, mental retardation occurs in 2.5 to 3 percent of the general population. About 6 to 7.5 million mentally retarded individuals live in the United States alone. Mental retardation begins in childhood or adolescence before the age of 18. In most cases, it persists throughout adulthood. A diagnosis of mental retardation is made if an individual has an intellectual functioning level well below average and significant limitations in two or more adaptive skill areas. Intellectual functioning level is defined by standardized tests that measure the ability to reason in terms of mental age (intelligence quotient or IQ). Mental retardation is defined as IQ score below 70 to 75. Adaptive skills are the skills needed for daily life. Such skills include the ability to produce and understand language (communication); home-living skills; use of community resources; health, safety , leisure, self-care, and social skills; self-direction; functional academic skills (reading, writing, and arithmetic); and work skills.

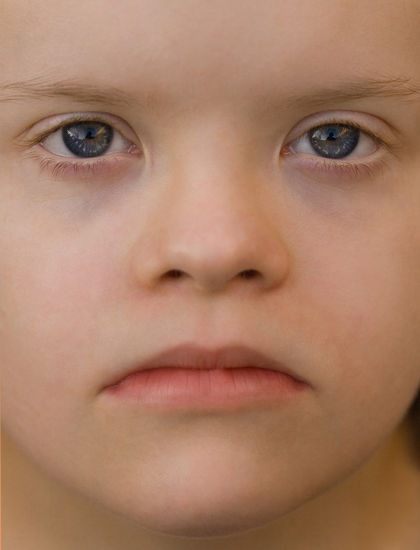

In general, mentally retarded children reach developmental milestones such as walking and talking much later than the general population. Symptoms of mental retardation may appear at birth or later in childhood. Time of onset depends on the suspected cause of the disability. Some cases of mild mental retardation are not diagnosed before the child enters preschool . These children typically have difficulties with social, communication, and functional academic skills. Children who have a neurological disorder or illness such as encephalitis or meningitis may suddenly show signs of cognitive impairment and adaptive difficulties.

Mental retardation varies in severity. There are four different degrees of mental retardation: mild, moderate, severe, and profound. These categories are based on the functioning level of the individual.

Mild mental retardation

Approximately 85 percent of the mentally retarded population is in the mildly retarded category. Their IQ score ranges from 50 to 75, and they can often acquire academic skills up to the sixth grade level. They can become fairly self-sufficient and in some cases live independently, with community and social support.

Moderate mental retardation

About 10 percent of the mentally retarded population is considered moderately retarded. Moderately retarded individuals have IQ scores ranging from 35 to 55. They can carry out work and self-care tasks with moderate supervision. They typically acquire communication skills in childhood and are able to live and function successfully within the community in a supervised environment such as a group home.

Severe mental retardation

About 3 to 4 percent of the mentally retarded population is severely retarded. Severely retarded individuals have IQ scores of 20 to 40. They may master very basic self-care skills and some communication skills. Many severely retarded individuals are able to live in a group home.

Profound mental retardation

Only 1 to 2 percent of the mentally retarded population is classified as profoundly retarded. Profoundly retarded individuals have IQ scores under 20 to 25. They may be able to develop basic self-care and communication skills with appropriate support and training. Their retardation is often caused by an accompanying neurological disorder. The profoundly retarded need a high level of structure and supervision.

The American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR) has developed another widely accepted diagnostic classification system for mental retardation. The AAMR classification system focuses on the capabilities of the retarded individual rather than on the limitations. The categories describe the level of support required. They are: intermittent support, limited support, extensive support, and pervasive support. Intermittent support, for example, is support needed only occasionally, perhaps during times of stress or crisis. It is the type of support typically required for most mildly retarded individuals. At the other end of the spectrum, pervasive support, or life-long, daily support for most adaptive areas, would be required for profoundly retarded individuals.

Demographics

For children, the mental retardation rate is 11.4 per 1,000 and varies approximately nine fold, ranging from 3.2 in New Jersey to 31.4 in Alabama. For adults, the rate is 6.6 and varies approximately six fold, ranging from 2.5 in Alaska to 15.7 in West Virginia. In 42 states, the rate for children is higher than that for adults; in seven states, the rate for adults is higher, and in two states, both rates are similar. The correlation between state-specific rates for children and for adults is 0.66. Overall, 69 percent of the state-specific variation in prevalence rates for adults is accounted for by median household income, the percentage of total births to teenaged mothers, and the percentage of the population with less than a ninth-grade education. Low educational attainment was the most important correlate of mental retardation rates among adults.

Causes and symptoms

Low IQ scores and limitations in adaptive skills are the hallmarks of mental retardation. Aggression, self-injury, and mood disorders are sometimes associated with the disability. The severity of the symptoms and the age at which they first appear depend on the cause. Children who are mentally retarded reach developmental milestones significantly later than expected, if at all. If retardation is caused by chromosomal or other genetic disorders, it is often apparent from infancy. If retardation is caused by childhood illnesses or injuries, learning and adaptive skills that were once easy may suddenly become difficult or impossible to master. In about 35 percent of cases, the cause of mental retardation cannot be found. Biological and environmental factors that can cause mental retardation include genetics, prenatal illnesses and issues, childhood illnesses and injuries, and environmental factors.

Genetics

About 5 percent of mental retardation is caused by hereditary factors. Mental retardation may be caused by an inherited abnormality of the genes, such as fragile X syndrome . Fragile X, a defect in the chromosome that determines sex, is the most common inherited cause of mental retardation. Single gene defects such as phenylketonuria (PKU) and other inborn errors of metabolism may also cause mental retardation if they are not found and treated early. An accident or mutation in genetic development may also cause retardation. Examples of such accidents are development of an extra chromosome 18 (trisomy 18) and Down syndrome . Down syndrome is caused by an abnormality in the development of chromosome 21. It is the most common genetic cause of mental retardation.

Prenatal illnesses and issues

Fetal alcohol syndrome affects one in 600 children in the United States. It is caused by excessive alcohol intake in the first twelve weeks (trimester) of pregnancy. Some studies have shown that even moderate alcohol use during pregnancy may cause learning disabilities in children. Drug abuse and cigarette smoking during pregnancy have also been linked to mental retardation.

Maternal infections and illnesses such as glandular disorders, rubella , toxoplasmosis , and cytomegalovirus infection may cause mental retardation. When the mother has high blood pressure ( hypertension ) or blood poisoning (toxemia), the flow of oxygen to the fetus may be reduced, causing brain damage and mental retardation.

Birth defects that cause physical deformities of the head, brain, and central nervous system frequently cause mental retardation. Neural tube defect, for example, is a birth defect in which the neural tube that forms the spinal cord does not close completely. This defect may cause children to develop an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid on the brain ( hydrocephalus ). By putting pressure on the brain hydrocephalus can cause learning impairment.

Childhood illnesses and injuries

Hyperthyroidism, whooping cough, chickenpox, measles , and Hib disease (a bacterial infection) may cause mental retardation if they are not treated adequately. An infection of the membrane covering the brain (meningitis) or an inflammation of the brain itself (encephalitis) cause swelling that in turn may cause brain damage and mental retardation. Traumatic brain injury caused by a blow or a violent shake to the head may also cause brain damage and mental retardation in children.

Environmental factors

Ignored or neglected infants who are not provided the mental and physical stimulation required for normal development may suffer irreversible learning impairments. Children who live in poverty and suffer from malnutrition , unhealthy living conditions, and improper or inadequate medical care are at a higher risk. Exposure to lead can also cause mental retardation. Many children develop lead poisoning by eating the flaking lead-based paint often found in older buildings.

When to call the doctor

If mental retardation is suspected, a comprehensive physical examination and medical history should be done immediately to discover any organic cause of symptoms. Conditions such as hyperthyroidism and PKU are treatable. If these conditions are discovered early, the progression of retardation can be stopped and, in some cases, partially reversed. If a neurological cause such as brain injury is suspected, the child may be referred to a neurologist or neuropsychologist for testing.

The symptoms of mental retardation are usually evident by a child's first or second year. In the case of Down syndrome, which involves distinctive physical characteristics, a diagnosis can usually be made shortly after birth. Mentally retarded children lag behind their peers in developmental milestones such as smiling, sitting up, walking, and talking. They often demonstrate lower than normal levels of interest in their environment and responsiveness to others, and they are slower than other children in reacting to visual or auditory stimulation. By the time a child reaches the age of two or three, retardation can be determined using physical and psychological tests . Testing is important at this age if a child shows signs of possible retardation because alternate causes, such as impaired hearing, may be found and treated.

Diagnosis

A complete medical, family , social, and educational history is compiled from existing medical and school records (if applicable) and from interviews with parents. Children are given intelligence tests to measure their learning abilities and intellectual functioning. Such tests include the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, the Wechsler Intelligence Scales, the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, and the Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children. For infants, the Bayley Scales of Infant Development may be used to assess motor, language, and problem-solving skills. Interviews with parents or other caregivers are used to assess the child's daily living, muscle control, communication, and social skills. The Woodcock-Johnson Scales of Independent Behavior and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS) are frequently used to test these skills.

Treatment

Federal legislation entitles mentally retarded children to free testing and appropriate, individualized education and skills training within the school system from ages three to 21. For children under the age of three, many states have established early intervention programs that assess, recommend, and begin treatment programs. Many day schools are available to help train retarded children in basic skills such as bathing and feeding themselves. Extracurricular activities and social programs are also important in helping retarded children and adolescents gain self-esteem .

Training in independent living and job skills is often begun in early adulthood. The level of training depends on the degree of retardation. Mildly retarded individuals can often acquire the skills needed to live independently and hold an outside job. Moderate to profoundly retarded individuals usually require supervised community living. Family therapy can help relatives of the mentally retarded develop coping skills. It can also help parents deal with feelings of guilt or anger. A supportive, warm home environment is essential to help the mentally retarded reach their full potential. However, as of 2004, there is no cure for mental retardation.

A promising but controversial treatment for mental retardation involves stem cell research. In the early 2000s scientists are exploring the potential of adult stem cells in treating mental retardation. They have transplanted bone marrow cells into living embryos in the uteri of animals to approach congenital diseases, birth defects, and mental retardation. Stem cells are primitive cells that are capable of forming diverse types of tissue. Because of this remarkable quality, human stem cells hold huge promise for the development of therapies to regenerate damaged organs and heal people who are suffering from terrible diseases. Embryonic stem cells are derived from human embryos. Their use is controversial because such stem cells cannot be used in research without destroying the living embryo. Other sources of stem cells are available, however, and can be harvested from umbilical cord blood as well as from fat, bone marrow, and other adult tissue without harm to the donor. An enormous amount of research involving adult stem cells is going on as of 2004 in laboratories in the United States.

Prognosis

Individuals with mild to moderate mental retardation are frequently able to achieve some self-sufficiency and to lead happy and fulfilling lives. To reach these goals, they need appropriate and consistent educational, community, social, family, and vocational supports. The outlook is less promising for those with severe to profound retardation. Studies have shown that these individuals have a shortened life expectancy. The diseases that are usually associated with severe retardation may cause the shorter life span. People with Down syndrome develop in later life the brain changes that characterize Alzheimer's disease and may develop the clinical symptoms of this disease as well.

Prevention

Immunization against diseases such as measles and Hib prevents many of the illnesses that can cause mental retardation. In addition, all children should undergo routine developmental screening as part of their pediatric care. Screening is particularly critical for those children who may be neglected or undernourished or may live in disease-producing conditions. Newborn screening and immediate treatment for PKU and hyperthyroidism can usually catch these disorders early enough to prevent retardation. Good prenatal care can also help prevent retardation. Pregnant women should be educated about the risks of drinking and the need to maintain good nutrition during pregnancy. Tests such as amniocentesis and ultrasonography can determine whether a fetus is developing normally in the womb.

Parental concerns

All states are required by law to offer early intervention programs for mentally retarded children from the time they are born. The sooner the diagnosis of mental retardation is made, the more the child can be helped. With mentally retarded infants, the treatment emphasis is on sensorimotor development, which can be stimulated by exercises and special types of play . It is required that special education programs be available for retarded children starting at three years of age. These programs concentrate on essential self-care, such as feeding, dressing, and toilet training . There is also specialized help available for language and communication difficulties and physical disabilities. As children grow older, training in daily living skills, as well as academic subjects, is offered.

Counseling and therapy are another important type of treatment for the mentally retarded. Retarded children are prone to behavioral problems caused by short attention span, low tolerance for frustration, and poor impulse control. Behavior therapy with a mental health professional can help combat negative behavior patterns and replace them with more functional ones. A counselor or therapist can also help retarded children cope with the low self-esteem that often results from the realization that they are different from other children, including siblings. Counseling can also be valuable for the family of a retarded child to help parents cope with painful feelings about the child's condition and with the extra time and patience needed for the care and education of a special-needs child. Siblings may need to talk about the pressures they face, such as accepting the extra time and attention their parents must devote to a retarded brother or sister. Sometimes parents have trouble bonding with an infant who is retarded and need professional help and reassurance to establish a close and loving relationship.

Current social and healthcare policies encourage keeping mentally retarded persons in their own homes or in informal group home settings rather than institutions. The variety of social and mental health services available to the mentally retarded, including pre-vocational and vocational training, are geared toward making this possible.

KEY TERMS

Amniocentesis —A procedure performed at 16–18 weeks of pregnancy in which a needle is inserted through a woman's abdomen into her uterus to draw out a small sample of the amniotic fluid from around the baby for analysis. Either the fluid itself or cells from the fluid can be used for a variety of tests to obtain information about genetic disorders and other medical conditions in the fetus.

Developmental delay —The failure of a child to meet certain developmental milestones, such as sitting, walking, and talking, at the average age. Developmental delay may indicate a problem in development of the central nervous system.

Down syndrome —A chromosomal disorder caused by an extra copy or a rearrangement of chromosome 21. Children with Down syndrome have varying degrees of mental retardation and may have heart defects.

Hib disease —An infection caused by Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib). This disease mainly affects children under the age of five. In that age group, it is the leading cause of bacterial meningitis, pneumonia, joint and bone infections, and throat inflammations.

Inborn error of metabolism —One of a group of rare conditions characterized by an inherited defect in an enzyme or other protein. Inborn errors of metabolism can cause brain damage and mental retardation if left untreated. Phenylketonuria, Tay-Sachs disease, and galactosemia are inborn errors of metabolism.

Phenylketonuria (PKU) —A rare, inherited, metabolic disorder in which the enzyme necessary to break down and use phenylalanine, an amino acid necessary for normal growth and development, is lacking. As a result, phenylalanine builds up in the body causing mental retardation and other neurological problems.

Trisomy —An abnormal condition where three copies of one chromosome are present in the cells of an individual's body instead of two, the normal number.

Ultrasonography —A medical test in which sound waves are directed against internal structures in the body. As sound waves bounce off the internal structure, they create an image on a video screen. Ultrasonography is often used to diagnose fetal abnormalities, gallstones, heart defects, and tumors. Also called ultrasound imaging.

Resources

BOOKS

Ainsworth, Patricia, and Pamela Baker. Understanding Mental Retardation. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2004.

Libal, Autumn. My Name Is Not Slow: Youth with Mental Retardation. Broomall, PA: Mason Crest Publishers, 2004.

Wehmeyer, Michael L., et al. Teaching Students with Mental Retardation: Providing Access to the General Curriculum. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Co., 2001.

PERIODICALS

Cinamon, Rachel Gali, and Limor Gifsh. "Conceptions of Work among Adolescents and Young Adults with Mental Retardation." Career Development Quarterly 52 (March 2004): 212–24.

Howard, Barbara J. "Mental Retardation Challenges." Pediatric News 38 (September 2004): 20–1.

Kerker, Bonnie D., et al. "Mental Health Disorders among Individuals with Mental Retardation: Challenges to Accurate Prevalence Estimates." Public Health Reports 119 (August 2004): 409–17.

Ly, Tran M., and Robert M. Hodapp. "Maternal Attribution of Child Noncompliance in Children with Mental Retardation: Down Syndrome versus Other Causes." Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 23 (October 2002): 322–29.

ORGANIZATIONS

American Association on Mental Retardation. 444 North Capitol Street NW, Suite 846, Washington, DC 20001–1512. Web site: http://www.aamr.org.

National Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 3615 Wisconsin Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20016. Web site: http://www.aacap.org.

WEB SITES

"Introduction to Mental Retardation." The Arc , 2004. Available online at http://www.thearc.org/faqs/mrqa.html (accessed November 11, 2004).

"Mental Retardation." National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities , January 2004. Available online at http://www.nichcy.org/pubs/factshe/fs8txt.htm (accessed November 11, 2004).

"Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , January 26, 1996. Available online at http://www.cdc/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00040023.htm (accessed November 11, 2004).

Paula Anne Ford-Martin Ken R. Wells

Tonight she was taking a shower and called me to come in because she needed help with something. She had pushed all the bottles that were along the edge into the tub, I asked her to please pick them up and she told me NO very defiantly, she then told me to get out of the bathroom. She became very irritable and uncontrollable which often happens. It is sometimes very difficult to just walk away. I yelled at her and said things that I know hurt her feelings. I regret saying things like this to her, I'm unsure of how to get her to understand how her behavior affects me, her father and brother. She is getting counseling for an incident that occured last summer and our family is going to learn how to better cope with some of her behavioral issues. Any input? I want to do what is best for my daughter, but know I'm going about it all the wrong way.

Good to read details of about intellectual disability (ID) / Mental Retardation.

Thanks & kind regards