Special education

Definition

Special education refers to a range of educational and social services provided by the public school system and other educational institutions to individuals with disabilities who are between three and 21 years of age.

Purpose

Special education is designed to ensure that students with disabilities are provided with an environment that allows them to be educated effectively. Disabilities that qualify for special education include physical disabilities, such as deafness or blindness; mental disabilities, such as Down's syndrome and autism ; medical conditions, such as oxygen dependence or traumatic brain injury; learning deficits, such as dyslexia ; and behavioral disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorders.

In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHCA, PL 94-142) mandated that states provide a "free and appropriate public education" (FAPE) to all students, including those with physical, mental, or behavioral disabilities. This special education must include a comprehensive screening and diagnosis by a multi-disciplinary team and the development of an annual Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for each student, outlining academic and behavioral goals, services to be provided, and methods of evaluation. The student's parents must consent to initial screening and must be invited to participate in all phases of the process.

In 1997, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) expanded special education services by mandating that all children with disabilities—regardless of the type or severity of their disability—between the ages of three and 21 years are entitled to FAPE in the least restrictive environment. That is, children requiring special education must by educated with nondisabled children to the maximum extent possible in an appropriate program to meet their special needs. While the majority of children with disabilities are taught at least parttime in a general classroom setting, many children are segregated, most often due to a lack of staff and resources to support special needs students in general classrooms. This stipulation that special-needs children be educated in the least restrictive environment led to the practice of mainstreaming, which is the policy of placing special education students in regular classrooms as much as possible and using separate resource rooms where the students receive special tutoring, review, and instruction.

Although gifted and talented students are not usually considered candidates for special education and there is no federal mandate to support these students, exceptionally gifted children may also be entitled to receive special education services. Gifted children who are not identified and continue to be taught in a general classroom may develop behavioral issues due to boredom. Specially designed gifted education programs are available in many school districts. In addition, bilingual children may require special education services. Children whose native language is not English may not receive appropriate education due to their language barrier. Bilingual language support services should be provided.

Description

Special education can include a range of support services, depending on the special needs of the student. Support services may involve physical assistance and therapy, counseling and psychotherapy, modified learning environments and assistive learning devices, educational and psychological assessments, and behavioral modification techniques.

According to U.S. Department of Education statistics, approximately 600,000 children aged three to five years were served by special education services in 2001. In preschool children, the most prevalent disability was speech or language impairment. Approximately 5.8 million students aged six to 21 years were served by special education services in 2001. Common disabilities include specific learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia), speech or language impairment, mental retardation , and emotional disturbance.

In order to qualify for special education a child must be diagnosed as having a disability and the disability must be found to "adversely affect educational performance" so as to require special services. Referral and evaluation for special education varies widely. For children with severe disabilities, a physician and the parents usually identify and refer the child to special education. Other disabilities or deficits in the child's developing physical and cognitive abilities may be identified by teacher and parent observation or revealed by academic or developmental tests. Most school districts have standardized programs to screen large numbers of children between kindergarten and third grade. Other disabilities may be subtle or compensated for, such as dyslexia, and may not be discovered until demands on the student increase in college. After referral, a meeting is held to determine whether the child should be assessed or evaluated to determine the type of disability he or she may have. Tests attempt to identify the cognitive (academic), social, or physical tasks that the child has difficulty performing and why the difficulty exists, i.e., what disability or disabilities are present. Tests may include: reading, writing, spelling, and math tests; psychological or intelligence tests; speech and language; vision and hearing tests; or an examination by a physician. Parents must consent to all testing, evaluation, and placement and can appeal most decisions if they disagree with the conclusions.

After disabilities and special needs are identified, an IEP is developed by school staff with input from the parents. The IEP development team is interdisciplinary and usually includes the special education teacher, another regular academic teacher, the parents, a school administrator, a school psychologist, and other school staff (e.g., nurse, coach, counselor). The IEP should be comprehensive and include the following:

- current performance measures based on multiple tests and assessment methods

- educational goals and objectives that define how problems will be addressed in the short and long term

-

definition of how the child's progress will be measured on an ongoing basis

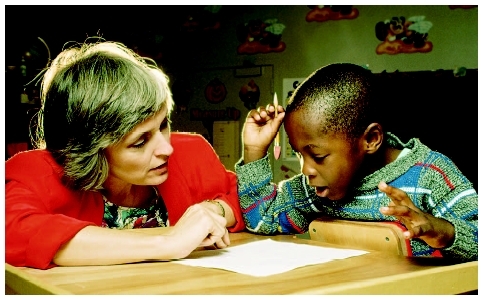

Special education student receiving one-on-one instruction.(© Richard T. Nowitz/Corbis.)

Special education student receiving one-on-one instruction.(© Richard T. Nowitz/Corbis.) - disciplinary methods (especially for children with emotional and behavioral issues)

- an individualized healthcare plan (IHP) for students also requiring special medical attention or medications

IEPs vary widely in length and complexity according to the type of disability. More effective IEPs specifically outline the child's needs; are mutually agreed upon by parents, teachers, and counselors; support activities that are typical of other students in the same age-group; promote school and community membership, and clearly facilitate the student's long-range life goals. Often IEPs do not specifically address how progress is to be measured. An effective IEP clearly defines the types of tests and assessments that are to be given to measure the child's progress. Although subjective assessment by teachers can provide valuable insight, objective tests that specifically measure academic and other skills must be included in the IEP.

After the IEP is developed, the student is placed in the appropriate educational setting. Certified special education teachers deliver programs in separate classrooms using modified educational curricula and specially designed assistive education techniques. Children with physical disabilities are provided with any assistive learning technology or equipment they need to complete educational requirements. Examples of such technology include special computers for speech/hearing/language assistance, modified desks, and writing support devices. Specially trained support staff assist students mainstreamed in general classrooms. When the public school cannot provide the appropriate environment and resources to meet the educational needs of the student, it is obligated to find and pay for an alternative educational setting, such as a day program in a mental/behavioral health facility, home schooling with appropriate medical/mental health support, an alternative school dedicated to serving disabled children, or a private school with special education support services.

Parental concerns

Children with disabilities and their parents have certain legal rights, most importantly, the right to challenge any recommendation made by a school and its staff. Parents who disagree with the school's educational program can hire legal representation, request formal and informal hearings (due process), and obtain additional evaluation from an independent consultant.

Children with emotional disturbances and related behavioral disorders have historically been unrecognized as being eligible for special education services. However, emotional problems can in fact act as a barrier to education. For children with emotional disturbances to qualify for special education, evidence from psychological testing and observation (by teachers or therapists) must demonstrate that the emotional issues significantly affect educational performance. Most public schools do not have the staff and resources to handle children with emotional disturbances, in addition to other children with disabilities. Many alternative schools exist for children with emotional disturbances and behavioral disorders who have average and above-average academic abilities. If the public school cannot adequately provide FAPE for such students, parents can seek legal representation to obtain funding from the public school for their child to attend an appropriate alternative school. Students with emotional disturbances and behavioral disorders should have mental health support services integrated with their IEP.

According to parents, 14 percent of students with disabilities in elementary and middle school had been expelled or suspended at some point in their school careers. And special needs children have a high drop-out rate—approximately 25 percent drop out of school and another 20 percent leave for other reasons. Emotionally disturbed students have the highest drop-out rate (35%), according to Department of Education statistics, while deaf-blind students have the lowest rate (4%). Graduation and employment rates for students with disabilities rose through the two decades that followed the passage of EHCA and IDEA and other disability legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act. Depending on the disability, as many as 45 to 70 percent of disabled adults may remain unemployed. However, some special needs students are quite successful. Students with learning disabilities and speech disorders have the lowest rates of unemployment, usually because they have participated in vocational education programs with a comprehensive vocational assessment, including assessment of independent living skills.

KEY TERMS

Alternative school —An educational setting designed to accommodate educational, behavioral, and/or medical needs of children and adolescents that cannot be adequately addressed in a traditional school environment.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) —A condition in which a person (usually a child) has an unusually high activity level and a short attention span. People with the disorder may act impulsively and may have learning and behavioral problems.

Dyslexia —A type of reading disorder often characterized by reversal of letters or words.

Individualized educational plan (IEP) —A detailed description of the educational goals, assessment methods, behavioral management plan, and educational performance of a student requiring special education services.

Resources

BOOKS

Gargiulo, Richard M. Special Education in Contemporary Society. Florence, KY: Wadsworth Publishing, 2005.

Kaufman, James, et al. Exceptional Learners: Introduction to Special Education. New York: Allyn & Bacon, 2005.

Kunjufu, Jawanza. Keeping Black Boys Out of Special Education. Chicago, IL: African American Images, 2005.

Wright, Peter W., and Pamela Darr Wright. From Emotions to Advocacy: The Special Education Survival Guide. Hartfield, VA: Harbor House Law Press, 2002.

PERIODICALS

Dalton, M. A. "Education Rights and the Special Needs Child." Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinicals of North America 11 (2002): 859–68.

Heller, K. W., and J. Tumlin. "Using expanded individualized health care plans to assist teachers of students with complex health care needs." Journal of School Nursing 20 (June 2004): 150–60.

Weist, Mark D., and Kathleen E. Albus. "Expanded School Mental Health." Behavior Modification 28 (July 2004): 463–71.

ORGANIZATIONS

Council for Exceptional Children. 1110 North Glebe Road, Suite 300, Arlington, VA 22201. Web site: http://www.cec.sped.org/.

MAX Foundation. PO Box 22, Rockville Center, New York, NY 11571. Web site: http://maxfoundation.org/ .

WEB SITES

Internet Special Education Resources. Available online at http://www.iser.com/index.shtml (accessed November 4,2004).

Special Education Resources on the Internet (SERI). Available online at http://www.seriweb.com/ (accessed November 4,2004).

Wright, Peter W., and Pamela Darr Wright. "Your Child's IEP: Practical and Legal Guidance for Parents." Wrightslaw. Available online at http://www.wrightslaw.com/advoc/articles/iep_guidance.html (accessed November 4,2004).

Jennifer E. Sisk, M.A.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: