Atrial septal defect

Definition

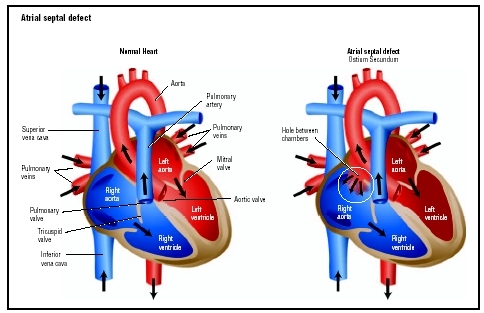

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is an abnormal opening in the muscular wall separating the left and right upper chambers (atria) of the heart.

Description

During normal development of the fetal heart, there is an opening in the wall (septum) separating the left and right upper chambers of the heart. Normally, the opening closes before birth, but if it does not, the child is born with a hole between the left and right atria. This abnormal opening is called an atrial septal defect and causes blood from the left atrium to flow (or "shunt") across the hole into the right atrium.

Different types of atrial septal defects occur, and they are classified according to where in the separating wall they are found. The most commonly found atrial septal defect, called secundum atrial septal defect, occurs in the middle of the atrial septum and accounts for about 70 percent of all atrial septal defects.

Abnormal openings also form in the upper part of the atrial septum (called sinus venosus ASD) where the superior vena cava and right atrium join, and lower parts of the atrial septum (called primum ASD). A sinus venosus ASD usually involves the right upper pulmonary vein, while a primum ASD often occurs along with an abnormality in the mitral valve and/or tricuspid valve, and causes some blood leakage (regurgitation) back through the valves.

Atrial septal defects can occur alone or in combination with other congenital heart disorders, such as ventricular septal defect. They can be as small as a pinpoint or as large as the space where the entire septum should be located.

Demographics

Atrial and ventricular septal defects are the most common congenital heart defects. Atrial septal defect accounts for 4–10 percent of all cases of congenital heart disease in the United States. Abnormal openings in the atrial septum are twice as common in females as in males.

Causes and symptoms

Causes

Abnormal openings in the atrial septum occur during fetal development. These abnormalities can go unnoticed if the opening is small and produces no abnormal symptoms. If the defect is large, oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium flows back into the right atrium and gets pumped back to the lungs again, causing more work for the heart and lungs. The right atrium may swell or enlarge to hold the extra blood.

In some cases, an atrial septal defect can allow blood clots from the body to enter the brain and cause a stroke . Untreated atrial septal defect can lead to pulmonary hypertension , chest infection, Eisenmenger's syndrome, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, stroke, or right-sided heart failure.

Symptoms

A person born with an atrial septal defect may have no symptoms in childhood, and the condition may go undetected into adulthood. Stunted growth may be a symptom of atrial septal defect. Other symptoms that might develop over time include:

- shortness of breath

- fainting

- irregular heart beats or palpitations (abnormal heart beats that feel like fluttering in the chest)

- inability to exercise without becoming over-tired

- difficulty breathing with exercise or activity

By age 50, most people with atrial septal defects experience symptoms that interfere with activities of daily living.

When to call the doctor

The parent or caregiver should call the child's pediatrician or cardiologist when the child has these symptoms or conditions:

- swelling in the ankles or feet

- swollen abdomen

- poor exercise tolerance

- recurrent chest colds and respiratory infections

- abnormal blood pressure

- signs of infection, including sore throat , general body aches, or fever

The parent or caregiver should seek emergency treatment by calling 911 in most areas when the child has these symptoms or conditions:

- breathing difficulties or rapid breathing

- dizziness or fainting

- uncontrolled coughing or coughing with blood

- bluish skin tone or bluish coloration around the lips, fingernail beds, and tongue

- irregular heart beats or palpitations (abnormal heart beats that feel like fluttering in the chest)

- chest pain (rare in children)

Diagnosis

The medical and family history help the physician determine if the child has any conditions or disorders that might contribute to or cause the heart defect. A family history of heart defects may suggest a genetic predisposition to the condition.

During the physical exam, the child's blood pressure is measured, and a stethoscope is used to listen to sounds made by the heart and blood flowing through the arteries. Some heart murmurs (abnormal heart sounds) can indicate an atrial septal defect. The child's pulse, reflexes, height, and weight are checked and recorded. The child's blood oxygen level can be measured using a pulse oximeter, a sensor placed on the fingertip or earlobe. Internal organs are palpated, or felt, to determine if they are enlarged.

A chest x ray, electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG), echocardiogram (echo), or magnetic resonance imaging MRI) can confirm the presence of an atrial septal defect. A chest x ray evaluates the size, shape, and location of the heart and lungs.

An electrocardiogram helps the physician evaluate the electrical activity of the heart. During an EKG, small electrode patches are attached to the skin on the chest. The electrodes are connected to a computer that measures the heart's electrical impulses and records them in a zigzag patter on a moving strip of paper.

An echocardiogram uses ultrasound, or high-frequency sound waves, to display an image of the heart's internal structures. It can detect valve and other heart problems. A Doppler echo uses sound waves to measure blood flow.

Magnetic resonance imaging is a scanning method that uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create three-dimensional images of the heart, which reveal how blood flows through the heart and how the heart is working.

In some cases, cardiac catheterization, a more invasive diagnostic procedure, may be performed to diagnose atrial septal defect. This procedure should be performed by a specially trained physician and diagnostic team in a well-equipped heart center. During the procedure, a long, slender tube called a catheter is inserted into a vein or artery and slowly directed to the heart, using x ray guidance. To better view the heart and blood vessels, contrast material (dye) is injected through the catheter and viewed and recorded on an x ray video as it moves through the heart. This imaging technique is called angiography. The catheter measures the amount of oxygen present in the blood within the heart. If the heart has an opening between the atria, oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium enters the right atrium. The cardiac catheterization can help doctors detect the higher-than-normal amount of oxygen in the heart's right atrium and right ventricle, and in the large blood vessels that carry blood to the lungs, where the blood would normally collect its oxygen.

Treatment

Twenty percent of atrial septal defects in children correct themselves without medical treatments by the time a child is two years old. If the opening does not close on its own, it needs to be repaired to prevent the pulmonary arteries from becoming thickened and blocked due to increased blood flow. If this condition (pulmonary vascular obstructive disease) is left untreated, it can increase the risk of death by 25 percent.

Treatment should be provided by a pediatric cardiologist, a specialist trained to diagnose and treat congenital heart disease. Surgery should be performed by a pediatric cardiovascular surgeon. A catheter-based cardiac implant should be done by an interventional cardiologist skilled in performing this procedure on children.

Surgery

There are two types of surgical repair for atrial septal defects: primary closure in which the opening is repaired with sutures alone if the defect is small; or secondary closure in which a patch closes the opening if the defect is large. The secondary closure may involve sewing a synthetic patch made of Dacron material over the opening, or wrapping the patient's own tissue (often from the fluid-filled sac around the heart called the pericardium) to close the opening.

During traditional atrial septal defect surgery, the heart is exposed through an incision made in the chest or between the ribs. A heart-lung bypass machine pumps blood for the heart while the heart is stopped and the wall defect is being repaired. Recuperation from surgery involves three to five days in the hospital and four to six weeks recovering at home. When possible, minimally-invasive surgical techniques that use smaller incisions (3–4 inches [7–10 cm]) may be performed, depending on the size and location of the defect. Minimally invasive surgery results in a much shorter hospital stay, reduced scarring, and a faster recovery than traditional surgery.

Surgical repair in asymptomatic children is usually recommended before the child begins grade school. Earlier surgical treatment is recommended when the child develops symptoms or has stunted growth.

Catheter-based cardiac implant procedure

A catheter-based cardiac implant procedure is less invasive than surgical repair, requires smaller incisions, does not require a heart-lung bypass machine, and results in a much shorter hospital stay, reduced scarring, and a more rapid recovery. The child usually stays in the hospital less than 24 hours after the procedure and returns to normal activities within one to two weeks.

The catheter-based cardiac implant procedure involves the implantation of a closure device that seals the defect. Closure devices cannot be used to treat all atrial septal defects, especially if the defect is large, if it is not centrally located within the atrial septum, or if there is not enough nearby tissue to adequately support the closure device. Other situations that prevent the use of a closure device include: very narrow blood vessels that will not allow the catheter-based system to be inserted; abnormalities of the heart valves; venous drainage from the lungs; and the presence of blood clots, bleeding disorders, active infections, or aspirin intolerance.

The procedure starts with a cardiac catheterization to determine the size and location of the defect. If the cardiac catheterization indicates that a closure device would be an effective treatment, an anticoagulant medication, is given intravenously to reduce the risk of blood clot. The closure device is placed through a specially designed catheter and guided to the location of the heart wall defect. The closure device stays in place permanently to stop the abnormal flow of blood between the atria. Over time, the heart tissue grows over the implanted closure device, becoming part of the heart. Although the device remains the same size, the heart tissue covering the device grows with the child.

Within 24 hours after the closure device implant procedure, a chest x ray, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram are performed to ensure that the device is properly placed.

Medications

Patients who undergo the cardiac implant procedure take a daily anticoagulant medication such as aspirin or warfarin (Coumadin) for three to six months after the procedure. This medication reduces the risk of blood clot formation around the closure device.

Diuretics may be prescribed if the atrial septal defect was diagnosed later in life and is causing fluid build-up. Diuretics aid the excretion of water and salts and help remove excess fluid from tissues. A potassium supplement may be prescribed with some diuretics to remove potassium from the body along with excess fluid. Other medications include Digoxin, which strengthens the contraction of the heart, slows the heartbeat, and removes fluid from tissues, and antihypertensive medications that treat high blood pressure.

Nutritional concerns

Infants and children with atrial septal defects may gain weight more slowly. The most common reason for poor growth is inadequate caloric or nutrient intake. Other factors that may interfere with growth include:

- rapid heart beat and increased breathing rate

- poor appetite

- decreased food intake due to rapid breathing and fatigue

- frequent respiratory infections

- poor absorption of nutrients from the digestive tract

- decreased oxygen in the blood

Babies with atrial septal defects tire quickly when they eat, making frequent feedings necessary. Feedings should be on-demand and may need to be as often as every two hours in the first few months. Some babies have difficulty feeding from a regular bottle nipple; parents may need to try different brands. If medications are prescribed, they should be given before a feeding. Medications should not be mixed in the formula or breast milk unless the doctor advises otherwise.

The pediatrician will advise when to introduce solid foods, usually around six months of age. Fat should not be restricted in the diet, especially in the first two years. High-calorie foods and snacks can play an important role in providing good nutrition and helping the child grow at a healthy rate.

In children older than two years of age, the following low-fat dietary guidelines are recommended:

- total fat intake should comprise 30 percent or less of total calories consumed per day

- calories consumed as saturated fat should equal no more than 8–10 percent of total calories consumed per day

- total cholesterol intake should be less than 300 mg/dl per day

A gradual transition to a heart-healthy diet can help decrease a child's adulthood risk of coronary artery disease and other health conditions. Foods high in fat should be replaced by grains, vegetables, fruits, lean meat, and other foods low in fat and high in complex carbohydrates and protein. Salt should not be added to foods while cooking; highly processed foods, which are usually high in sodium should be avoided. These items include fast foods, canned foods, boxed mixes, and frozen meals.

Follow-up care

Children with atrial septal defects require lifelong monitoring, even after a successful surgery or procedure to close the defect. Along with routine medical care and standard immunizations, periodic heart check-ups are necessary. Usually, heart check-up appointments are scheduled more frequently just after the diagnosis or following the treatment procedure. Additional immunizations, such as the influenza vaccine, may be recommended.

Medical identification

In case of emergency, a medical identification bracelet or necklace should be worn to alert all health care providers of the child's heart condition.

Prognosis

The outlook for children with atrial septal defects has improved markedly in the past two decades. Individuals with small defects can live a normal life, but larger defects require surgical correction. Less than 1 percent of people younger than age 45 die from corrective surgery. Five to ten percent of patients can die from the surgery if they are older than 40 and have other heart-related problems. There is a 25 percent lifetime risk of death if the atrial septal defect is not repaired. When an atrial septal defect is corrected within the first 20 years of life, there is an excellent chance for the child to live a normal and productive life.

Prevention

Atrial septal defects cannot be prevented. However, to protect patients with atrial septal defects and those with implanted closure devices from heart infections (endocarditis), the American Heart Association recommends regular dental check-ups to prevent infections of the mouth, as well as the preventive use of antibiotics . Preventive antibiotics should be taken before surgery, invasive tests or procedures, and all routine dental cleanings and procedures. A 2003 study reported that preventive antibiotics are underused in people with congenital heart conditions, possibly because they do not understand their increased risk of developing bacterial endocarditis.

Parental concerns

If the child needs surgery or a catheter-based cardiac implant, it is important for him or her to be as healthy as possible for the procedure. If the child has a fever, cough , or cold, the parent should inform the medical team to determine whether the procedure should be delayed. The medical team can help parents prepare the child for the procedure, and can instruct them on how to explain the procedure based on the child's age, ability to understand, and emotions. Once an atrial septal defect has been closed, it is unlikely that more surgery will be needed. Rarely, a patient may have a residual hole that may require further treatment, depending upon its size.

Most children with atrial septal defects can be fully active and are encouraged to exercise. An American Heart Association scientific statement advises children and teens with genetic heart conditions to seek advice from their doctors about the types of physical activities that are safe. The statement was intended to help doctors counsel patients who have an increased risk of sudden cardiac death during physical activity. Certain athletic activities such as competitive sports may be limited, depending on the child's type of defect and medical condition. A child with an atrial septal defect may tire more easily than other children; frequent breaks and rest periods should be encouraged as needed during activities. Parents should obtain a doctor's note to explain their child's specific exercise limitations to teachers and coaches.

A child with an atrial septal defect has a greater risk of having a child with a heart defect. The frequency of the condition increases from less than 1 percent in the general population to 2–20 percent when a parent is affected. Genetic counseling and further testing, such as chromosome analysis before pregnancy, or amniocentesis during pregnancy, may be recommended in adults with atrial septal defects.

Treatment and care for a child with an atrial septal defect can be costly, and some health insurance plans may not cover all expenses associated with a child's hospitalization or surgery. Help is available to cover medical expenses. The parents can discuss financial aid with the hospital. Some organizations, including The Heart of a Child Foundation and Little Hearts on the Mend Fund, provide financial assistance to children in need of heart surgery.

KEY TERMS

Atrial —Referring to the upper chambers of the heart.

Atrial fibrillation —A type of heart arrhythmia in which the upper chamber of the heart quivers instead of pumping in an organized way. In this condition, the upper chambers (atria) of the heart do not completely empty when the heart beats, which can allow blood clots to form.

Cardiac catheterization —A procedure to passes a catheter through a large vein into the heart and its vessels for the purpose of diagnosing coronary artery disease, assessing injury or disease of the aorta, or evaluating cardiac function.

Congenital —Present at birth.

Dacron —A synthetic polyester fiber used to surgically repair damaged sections of heart muscle and blood vessel walls.

Echocardiogram —A record of the internal structures of the heart obtained from beams of ultrasonic waves directed through the wall of the chest.

Eisenmenger's syndrome —A condition in which high pressures in the pulmonary arteries cause them to thicken. To compensate, the right side of the heart works harder, causing it to stretch and weaken. Eisenmenger's syndrome is a serious condition that leads to heart failure and can result in death by age 40 if left untreated.

Electrocardiagram (ECG, EKG) —A record of the electrical activity of the heart, with each wave being labeled as P, Q, R, S, and T waves. It is often used in the diagnosis of cases of abnormal cardiac rhythm and myocardial damage.

Heart failure —A condition in which the heart is unable to pump enough blood to supply the needs of the body

Pericardium —The thin, sac-like membrane that surrounds the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers: the inner, serous (or visceral) pericardium and the outer, fibrous (or parietal) pericardium.

Pulmonary hypertension —A disorder in which the pressure in the blood vessels of the lungs is abnormally high.

Septal —Relating to the septum, the thin muscle wall dividing the right and left sides of the heart. Holes in the septum are called septal defects.

Septum —A wall or partition. Often refers to the muscular wall dividing the left and right heart chambers or the partition in the nose that separates the two nostrils. Also refers to an abnormal fold of tissue down that center of the uterus that can cause infertility.

Ventricles —The lower pumping chambers of the heart. The ventricles push blood to the lungs and the rest of the body.

Caring for a child with an atrial septal defect is demanding. Support groups are available to help parents and caregivers cope with the challenges of providing care for children with special medical needs. It is important for parents to take care of themselves, too, by eating properly, exercising regularly, maintaining personal hygiene, keeping in contact with friends and family members for support, and managing stress by practicing relaxation techniques.

See also Congenital heart disease .

Resources

BOOKS

Bellenir, Karen, and Peter D. Dresser, eds. "If Your Child Has A Congenital Heart Defect" In Heart Diseases and Disorders Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Detroit, MI: Omnigraphics, Inc., 2000.

Friedman, William F., and John S. Child. "Disorders of the Cardiovascular System." In Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Dennis L. Kasper, et al., eds. New York: McGraw Hill, 2004.

McGoon, Michael D., ed. and Bernard J. Gersh, M.D. Mayo Clinic Heart Book: The Ultimate Guide to Heart Health. 2nd ed. New York: William Morrow and Co., Inc., 2000.

Topol, Eric J., M.D. "Pediatric and Congenital Heart Diseases." In Cleveland Clinic Heart Book: The Definitive Guide for the Entire Family from the Nation's Leading Heart Center. New York: Hyperion, 2000.

Trout, Darrell, and Ellen Welch. Surviving with Heart: Taking Charge of Your Heart Care. Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, 2002.

Wild, C. L., and M. J. Neary. Heart Defects in Children: What Every Parent Should Know. Minneapolis, MN: Chronimed Publishing, 2000.

PERIODICALS

"New Insight Offered into the Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease." Heart Disease Weekly (Oct.12, 2003): 3.

ORGANIZATIONS

Adult Congenital Heart Association (ACHA). 1500 Sunday Dr., Suite 102, Raleigh NC 27607-5151. (919) 861-4547. Web site: http://www.achaheart.org.

American College of Cardiology. Heart House. 9111 Old Georgetown Rd., Bethesda, MD 20814-1699. (800) 253-4636 ext. 694 or (301) 897-5400. Web site: http://www.acc.org.

American Heart Association. 7320 Greenville Ave., Dallas, TX 75231-4596. (214) 373-6300 or (800) 242-8721. Web site: http://www.americanheart.org/children.

Children's Heart Services. P.O. Box 8275, Bartlett, IL 60108-8275. (630) 415-0282. Web site: http://www.childrensheartservices.org.

The Cleveland Clinic Heart Center. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. 9500 Euclid Ave., F25, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195. (800) 223-2273 ext. 46697 or (216) 444-6697. Web site: http://www.clevelandclinic.org/heartcenter.

Congenital Heart Disease Information and Resources. 1561 Clark Dr., Yardley, PA 19067. Web site: http://www.tchin.org.

The Heart of a Child Foundation and Little Hearts on the Mend Fund. Provides financial assistance to children in need of heart surgery. 26710 Fond Du Lac Rd., Rancho Palos Verdes, CA 90275. (310) 375-6617. Web sites: http://www.heartofachild.org and http://www.littleheartsonthemend.org .

Heart Support of America. 4873 N. Broadway, Knoxville, TN 37918. Web site: http://www.heartsupport.com.

International Children's Heart Foundation. 1750 Madison, Suite 100, Memphis, TN 38104. (877) 869-4243. Web site: http://www.babyhearts.com.

Mended Little Hearts. Support program for parents of children with heart defects. (888)-HEART99. Web site: http://www.mendedhearts.org/MLH/mlh.htm.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. P.O. Box 30105, Bethesda, MD 20824-0105. (301) 251-1222. Web site: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov.

Texas Heart Institute. Heart Information Service. P.O. Box 20345, Houston, TX 77225-0345. Web site: http://www.tmc.edu/thi.

WEB SITES

HeartCenterOnline. Available online at: http://www.heartcenteronline.com .

The Heart: An Online Exploration. Developed by The Franklin Institute Science Museum with support from Unisys Corporation. The Franklin Institute Science Museum. 222 N. 20th St., Philadelphia, PA, 19103. (215) 448-1200. Available online at: http://www.sln2.fi.edu/biosci/heart.html.

Heart Information Network. Available online at: http://www.heartinfo.org.

Dominic De Bellis, Ph.D. Angela M. Costello

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: