Stroke

Definition

A stroke, also called a cerebral infarction, is a life-threatening condition marked by a sudden disruption in the blood supply to the brain.

Description

A disruption in the blood supply to the brain starves the brain of oxygen-rich blood and causes the nerve cells in that area to become damaged and die within minutes. The body parts controlled by those damaged brain cells lose their ability to function.

Depending on the area of the brain that is affected, a stroke can alter many aspects of a child's functioning such as speech, movement, behavior and learning. A stroke also may cause weakness or paralysis on one side of the body. The loss of function may be mild or severe, temporary or permanent.

If medical treatment begins within hours after symptoms are recognized, brain damage can be limited and the risk of permanent medical effects can be decreased.

Types of stroke

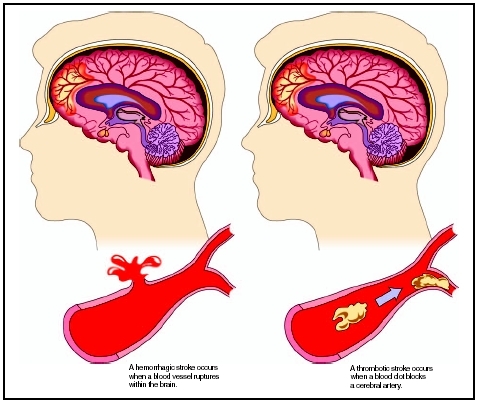

An ischemic stroke—the most common form of stroke in children under age 15—is caused by a blocked or narrowed artery. In children, blockages may be caused by a blood clot, injury to the artery, or rarely in children, atherosclerosis (build-up of fatty deposits on the blood vessel walls). A cerebral thrombosis is a blood clot that develops at the clogged part of the blood vessel. A cerebral embolism is a blood clot that travels to the clogged blood vessel from another location in the circulatory system.

A hemorrhagic stroke—the more common form of stroke in infants and children under age two—occurs when a weakened blood vessel leaks or bursts, causing bleeding in the brain tissue or near the surface of the brain.

Two types of weakened blood vessels usually cause hemorrhagic stroke, including:

- aneurysm: ballooning of a weakened area of a blood vessel

- arteriovenous malformations: cluster of abnormal blood vessels

A transient ischemic attack (TIA), also called a "mini stroke," is characterized by a short-term blood vessel obstruction or clot that tends to resolve itself quickly, usually within 10–20 minutes, or up to 24 hours. A TIA usually does not require intervention. However, a TIA is a strong indicator of an ischemic stroke and should be evaluated in the same way as a stroke to prevent a more serious attack.

In children, strokes can be categorized as:

- prenatal stroke: occurring before birth

- neonatal or perinatal stroke: occurring in infants less than 30 days old

- pediatric or childhood stroke: occurring in children aged 15 and under

Demographics

Childhood stroke is relatively rare, occurring in about two to three of every 100,000 children aged one to 14 per year. In comparison, stroke occurs in about 100 of every 100,000 adults per year. The rate of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke is similar among children aged one to 14.

Stroke occurs more frequently in children under age two, and peaks in the perinatal period. In the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1980-1998, the rate of stroke for infants less than 30 days old (per 100,000 live births per year) was 26.4, with rates of 6.7 for hemorrhagic stroke and 17.8 for ischemic stroke.

More fatal strokes occur in African-American children than white children, mirroring the racial differences of stroke in adults. Compared to the stroke risk of white children, African-American children have an increased relative risk of 2.12, Hispanics a decreased relative risk of 0.76 and Asians have a similar risk. Boys have a 1.28-fold higher risk of stroke than girls and have a higher case-fatality rate for ischemic stroke than girls. The increased risk among African Americans is not explained by the presence of sickle cell disease, nor is the excess risk among boys explained by trauma.

Research conducted by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) indicates a "stroke belt," or geographical area where fatal strokes are more predominant. This stroke belt includes Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. Researchers examined death certificates over a 19-year period and found a 21 percent higher risk of death from stroke in people under age 20 in the stroke belt states had compared with the same age group in other states. During the same period, people over age 25 in the stroke belt region had a 20 percent higher risk of death from stroke. Because the overall rate of stroke in children is low, researchers warn parents in these states not to be too alarmed. However, the findings indicate further investigation is needed.

Causes and symptoms

Causes

The cause of childhood stroke is unknown in one-third of cases, and an underlying medical condition or multiple conditions appear to contribute to over half of the cases. The most common causes of stroke are congenital (present at birth) and acquired heart diseases, and sickle cell anemia .

About 10–15 percent of children with sickle cell disease suffer a stroke, usually ischemic stroke. Sickle cell disease is a blood disorder in which the blood cells cannot carry oxygen to the brain because the blood vessels to the brain are either narrowed or closed.

One rare cause of stroke is an extreme case of the chickenpox virus, which causes a narrowing of blood vessels in the head for some children.

RISK FACTORS Although obesity , high cholesterol , high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and smoking are common stroke risk factors in adults, they rarely contribute to stroke risk in children. Risk factors for childhood stroke include a family history of stroke, cardiovascular disease or diabetes, as well as the presence of the conditions listed below.

Some of the more common congenital heart diseases that increase the risk of childhood stroke include:

- aortic and mitral valve stenosis

- atrial septal defect

- patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

- patent foramen ovale

- inherited blood clotting disorders

- ventricular septal defect

- hypercoagulable states

Some of the acquired heart conditions that increase the risk of childhood stroke include:

- bacterial meningitis

- endocarditis

- arrhythmia and atrial fibrillation

- artificial heart valve

- myocarditis

- cardiomyopathy

- rheumatic heart disease

- embolism

- anoxia

- antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

- encephalitis

- blood vessel disease

- certain blood disorders, such as hemophilia

- inborn errors of metabolism

- illicit drug use

- teenage pregnancy

- teen use of oral contraceptives (birth control pills)

Possible traumas that increase the risk of childhood stroke include birth injury or trauma, child abuse, or other injury or trauma.

Because of the wide range of secondary conditions that contribute to stroke, it is difficult for researchers to assess the relative contribution of each risk factor to the problem of cerebrovascular disease as a whole, according to the Child Neurology Society Ad Hoc Committee on Stroke in Children. In addition, this variability also hinders clinical research.

Symptoms

In infants and very young children, stroke symptoms are sudden and include:

- seizures

- coma

- paralysis on one side of the body

- nausea or vomiting

In older children, stroke symptoms are sudden and include:

- numbness or weakness of the face, arm, or leg, especially on one side of the body

- confusion or difficulty speaking or understanding speech

- vision difficulties, often in one eye

- hearing problems, often in one ear

- difficulty walking, dizziness or loss of balance or coordination

- severe headache

- difficulty swallowing

- nausea or vomiting

- painful or stiff neck

Other stroke signs and symptoms include:

- sudden severe headache with unknown cause

- sudden nausea or vomiting

- warm, flushed, clammy skin

- slow, full pulse

- appearance of unequal pupils

- facial "droop" on one side

- salivary drool

- urinary incontinence

If the child seems to recover quickly from these stroke symptoms, a TIA may have occurred. All neurological symptoms should serve as a stroke "warning sign" and could indicate a pending, more serious attack. The child should receive prompt evaluation so necessary preventive therapies can be initiated.

WHEN TO CALL THE DOCTOR If a child has any of the symptoms listed above, the parent or caregiver should immediately dial 9-1-1 to seek emergency care. It is important not to wait to see if symptoms subside; a stroke is a medical emergency. Until the paramedics arrive, the parent or caregiver should follow these first aid guidelines:

- Make sure the child is in a comfortable posture, lying on his or her side, so the airway does not become obstructed by drool or mucus.

- Talk reassuringly to the child, even if he or she is unconscious.

- Do not leave the child alone—constantly observe the child.

- Cover the child with a blanket or remove clothing as needed to maintain the child's normal body temperature.

- Do not give the child any medication, including aspirin; medication will be given later as needed.

Diagnosis

In most children, the diagnosis of stroke is delayed by more than 24 hours from the onset of symptoms. This delay is thought to occur because there is a lack of general awareness by physicians and families of cerebrovascular disorders in children. However, early recognition and treatment of a stroke could improve management, reduce the risk of brain damage and permanent disability, help prevent a recurrence, and initiate a proper treatment and rehabilitation program to maximize functional recovery.

The diagnosis of pediatric stroke generally occurs in the emergency room and includes:

- personal and family medical history

- review of current medications

- evaluation of other health problems

- physical examination

- brief neurological exam

- diagnostic tests

The medical history helps the physician evaluate the presence of other conditions or disorders that might have caused the stroke. The child's family medical history is evaluated to determine if there is a history of cardiovascular or neurological diseases that might increase the risk of blood clots.

The brief neurological exam includes a review of the patient's mental status, motor and sensory system, deep tendon reflexes, coordination, and walking pattern (gait). The cranial nerve function also will be evaluated and includes a review of the patient's visual function and eye movement, strength of facial muscles, the gag reflex, tongue and lip movements, ability to smell and taste, hearing, and sensation and movement of the face, head, and neck.

Questions about the child's condition may include:

- What symptoms occurred?

- When were the symptoms first noticed?

- How long did the symptoms last?

- What functions were affected?

During the physical exam, the child's pulse, blood pressure, and height and weight are checked and recorded.

Diagnostic tests include:

- Blood tests: Test used to detect the presence of any chemical abnormalities, infection, or blood clotting that may have caused the stroke.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan: An imaging technique that provides a detailed picture of the brain without the use of x rays. MRI uses a large magnet, radio waves and a computer to produce these images.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: An imaging technique that shows the blood vessels in the brain. A CT scan is used to identify the area of the brain affected and to detect signs of swelling.

- Chest x ray: X rays are used to detect an enlarged heart, vascular abnormalities, or lung problems.

- Angiogram: An invasive imaging technique used to examine the blood vessels in the brain. An angiogram is only performed if the CT or MRI scans do not show conclusive results.

- Echocardiogram (echo): A graphic outline of the heart's movement, valves and chambers, used to determine if the stroke was caused by a blood clot traveling from the heart to the brain. Echo is often combined with Doppler ultrasound and color Doppler. During the echo, an ultrasound transducer (hand-held wand placed on the skin of the chest) emits high-frequency sound waves to produce pictures of the heart's valves and chambers.

MRI is more sensitive than CT scanning for the diagnosis of an ischemic stroke within 24 hours. However, the two tests are comparable when used to evaluate the effects of a hemorrhagic stroke.

In rare cases or when carotid artery disease is suspected, additional tests may include a carotid ultrasound or cerebral or carotid angiogram. Other tests to diagnose stroke may include a transcranial Doppler ultrasound and neurosonogram. In a transcranial Doppler ultrasound, sound waves are used to measure blood flow in the vessels of the brain. In a neurosonogram, ultra high frequency sound waves are used to analyze blood flow and possible blockages in the blood vessels in or leading to the brain.

If a pediatric stroke is diagnosed, additional tests may be performed to assess the overall function

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): Electrodes (small, sticky metal patches attached to the scalp) are connected by wires (leads) to an electroencephalograph machine to chart the brain's continuous electrical activity.

- Evoked potentials study: Wires attached to the scalp, neck, and limbs are connected to a computer to measure the electrical activity in certain areas of the brain and spinal cord when specific sensory nerve pathways are stimulated. The brain's electrical response to visual, auditory, and sensual stimulation is recorded.

Treatment

Initial treatment depends on the type of stroke. For an ischemic stroke, initial emergent treatment focuses on restoring blood flow to the brain. For a hemorrhagic stroke, the goal of initial treatment is to control the bleeding. Children with a hemorrhagic stroke may be transferred to a center with neurosurgical facilities so the proper treatment, such as decompression or hydrocephalus drainage, can be provided by skilled specialists.

Emergency-room treatment may include: oxygen to ensure the brain is getting the maximum amount, control of body temperature, assessment and treatment of breathing difficulties, intravenous fluids to prevent or treat dehydration , and medications to control blood pressure and prevent blood clotting. Blood transfusions may be used to treat children with sickle cell disease.

Treatment team

Treatment should be provided by a pediatric neurologist and a multi-disciplinary team of specialists that may include a physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, social worker, and other specialists as needed to meet the child's individual needs.

Medications

Adult stroke patients who receive treatment within three hours after the onset of stroke symptoms may receive a "clot-busting" medication called t-PA. However, the diagnosis of stroke is rarely made within three hours, so the use of this drug in children is uncommon.

Anticoagulant medications, including heparin or warfarin and low-dose aspirin, may be used to reduce the risk of blood clot formation. Although experience with these medications in children suggests they are safe, their use in children remains controversial because of the risk of Reye's syndrome. Sometimes the potential benefits of these medications outweigh the small risk of side effects. Researchers agree that further studies are needed to determine the proper dosage and effectiveness of aspirin and other anticoagulant medications for treating stroke in children.

The most important medication guidelines are: 1) Ensure your child takes all medications exactly as prescribed; 2) Never discontinue any medication without first talking to the child's doctor, even if the medication does not seem to be working or is causing unwanted side effects; and 3) Follow-up with the child's health care provider as recommended to monitor the effects of the medication. Frequent blood tests are required for people taking anticoagulants to evaluate the dosage and effects of the medication.

Other stroke medications that are still being tested in clinical trials include:

- Citicoline as a treatment for ischemic stroke. Studies have shown both acute and long-term neuroprotective properties of citicoline in animal models of stroke and in several human clinical trials.

- Epoetin, a synthetic version of human erythropoietin, as a treatment for ischemic stroke. Epoetin aids the body in producing red blood cells and is currently used to treat anemia associated with kidney disease or caused by some drugs.

- Early administration of magnesium to serve as a potential neuroprotective agent. Studies have shown neuroprotectant properties of magnesium sulfate in animal models of stroke, and improved outcomes following magnesium sulfate treatment in humans have been observed following small pilot studies.

Rehabilitation

After the child's condition has stabilized, rehabilitation is initiated. Rehabilitation includes physical, occupational, and speech therapy. Therapy is usually initiated as soon as possible after a stroke and is often the most intense in the early stages of recovery. Clinicians should work with the child and the parents or caregivers to develop an individual treatment plan. Specific treatment goals will vary from one child to the next but will focus on restoring maximum function and independence, helping the child return to normal activities, and improving the child's quality of life. The child's progress after rehabilitation will depend upon which area of the brain was affected, the cause of stroke, the extent of injury, and the presence of other medical conditions.

Physical therapy includes stretching exercises, muscle group strengthening exercises, and range of motion exercises to preserve flexibility and range of motion. Exercises should be practiced daily, as recommended by the physical therapist. A physical therapist can instruct the patient on proper posture guidelines to maintain proper alignment of the hips and back. Balancing rest and exercise is also important.

Occupational therapy may include splints, casts, or braces on the affected arm or leg to enable proper limb positioning, prevent joint stiffness, and maintain flexibility and range of motion. An occupational therapist can recommend assistive equipment and devices to help the child with activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, and eating. If a walker or wheelchair are needed, an occupational therapist can provide specific instructions.

Physical and occupational therapists can provide guidelines on how to adapt the child's home and school environments to ensure safety and comfort.

Speech therapy will focus on the child's specific needs which may include any or all aspects of language use, such as speaking, reading, writing, and understanding the spoken word. Speech and language problems (aphasia) usually occur when a stroke affects the right side of the body.

Behavioral problems and learning disabilities, such as difficulties with attention or concentration, may become apparent when the child goes to school, so specific treatments and educational assistance may be needed to address these problems. A formal assessment can help parents identify potential behavioral and learning problems.

Surgery

The need for surgical treatment for pediatric stroke will depend on a number of factors, including the type of stroke, extent of damage from stroke, the child's age, and potential benefits and risks. Sometimes urgent surgery is necessary soon after the child is admitted to the emergency room to remove a blood clot and restore oxygen flow to the brain tissue.

Treatment options for hemorrhagic stroke may include surgery, sterotactic radiotherapy, or interventional neuroradiology to treat the underlying aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation.

There are several surgical procedures to repair an aneurysm that may have caused a hemorrhagic stroke. A clip may be placed across the neck of the aneurysm (like a clip at the end of a balloon) to stop the bleeding. A newer approach is to thread a long, thin tube through the artery that leads to the aneurysm. Then a tiny coil is fed through the tube into the aneurysm "balloon" to fill the space and seal off the bleeding.

An interventional procedure called carotid angioplasty may be performed to treat a blockage or blockages in the carotid arteries. During the procedure, a tiny balloon at the end of a long, thin tube (called a catheter) is pushed through the artery to the blockage. When the balloon is inflated, it opens the artery. In addition, a mesh tube (called a stent) may be placed inside the artery to help hold it open.

Carotid endarterectomy is a surgical procedure performed to remove a blockage from the carotid artery. During the operation, the surgeon scrapes away plaque from the wall of the artery so blood can flow freely through the artery to the brain.

Intracranial bypass surgery is a surgical procedure performed to restore blood flow around a blocked blood vessel in the brain. During the surgery, a healthy blood vessel, on the outside of the scalp, is re-routed to the part of the brain that is not getting enough blood flow. This new blood vessel bypasses the blocked vessel and provides an additional blood supply to areas of the brain that were deprived of blood. When blood flow is restored, the brain works normally, and the symptoms disappear. This procedure is not as common as the other surgical treatments listed above to treat pediatric stroke but it may be used to treat recurrent TIAs.

Alternative treatment

Alternative and complementary therapies include approaches that are considered to be outside the mainstream of traditional health care.

Techniques that induce relaxation and reduce stress, such as yoga , Tai Chi, meditation, guided imagery, and relaxation training, may be helpful in controlling blood pressure. Acupuncture and biofeedback training also may help induce relaxation. Before learning or practicing any particular technique, it is important for the parent/caregiver and child to learn about the therapy, its safety and effectiveness, potential side effects, and the expertise and qualifications of the practitioner. Although some practices are beneficial, others may be harmful to certain patients.

Alternative treatments should not be used as a substitute for medical therapies prescribed by a doctor. Parents should discuss these techniques and treatments with the child's doctor to determine the remedies that may be beneficial for the child.

Nutritional concerns

Dietary guidelines are individualized, based on the child's age, diagnosis, overall health, and level of functioning. Specific nutritional problems, such as swallowing or feeding difficulties, may be a concern in some patients and should be managed by a team of specialists including a speech therapist. Early identification, treatment, and correction of specific feeding problems will improve the health and nutritional status of the child.

A child's self-feeding skills can impact his or her health outcome. One study indicated that 90 percent of children with good to fair motor and feeding skills reached adulthood. In contrast, a lack of self-feeding skills was associated with a six-fold increase in mortality (rate of death).

Maintaining a healthy weight is important to prevent the development of chronic diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure ( hypertension ), and heart disease.

Tube feedings may be required in some patients with failure to thrive , aspiration pneumonia , difficulty swallowing, or an inability to ingest adequate calories orally to maintain nutritional status or promote growth.

A well-balanced and carefully planned diet will help maintain general good health for children who have suffered a stroke. In general, children should follow the same low-fat, high fiber diet that is recommended for the general population.

In children older than age two, the following low-fat dietary guidelines are recommended:

- Total fat intake should comprise 30 percent or less of total calories consumed per day.

- Calories consumed as saturated fat should equal no more than 8-10 percent of total calories consumed per day.

- Total cholesterol intake should be less than 300 mg/dl per day.

If the child has high blood pressure, the DASH diet is recommended. The "Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)" study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), showed that elevated blood pressures were reduced by an eating plan that emphasized fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy foods and was low in saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol. The DASH diet includes whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts. Fats, red meats, sodium, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages are limited. Sodium should also be reduced to no more than 1,500 milligrams per day.

Prognosis

Cerebrovascular disorders are among the top 10 causes of death in children, with rates highest in the first year of life. From 1979 to 1998 in the United States, childhood mortality from stroke declined sharply, by 58 percent, with reductions in all major subtypes: ischemic stroke decreased by 19 percent, subarachnoid hemorrhage by 79 percent, and intracerebral hemorrhage by 54 percent.

Some children survive a pediatric stroke with no life-long consequences. In other children, long-term complications of stroke may develop right away or within months to years after a stroke. According to a 2000 study published in the Journal of Child Neurology , the outcome of childhood stroke was a moderate or severe deficit in 42 percent of cases. Adverse outcomes after childhood stroke—including death in 10 percent, recurrence in 20 percent, and neurological deficits in two-thirds of survivors—can be reduced with available stroke treatments.

When a stroke affects a child whose brain is still developing, it is thought that the developing brain may be able to compensate for the functions that were lost as a result of a stroke.

Recovery from stroke is different with each child. Overall, the degree of permanent disability after a stroke is less in children than in adults. Speech and language problems usually improve rapidly in the first year after a stroke. Children may only have minor delays in the development of coordinated movement or in cognitive functioning. Almost all children recover the ability to walk independently after a stroke, unless there is another condition that causes disability. Recovery of function in the affected arm and hand is usually the most significant movement problem after a stroke. Most children who suffer from a stroke can expect to lead independent lives as adults.

Prevention

Despite current treatment, one out of 10 children with ischemic stroke will have a recurrence within five years. Although there is a high risk of repeat strokes in patients with sickle cell anemia, the risk can be reduced with regular blood transfusions. If no cause of the stroke was identified, the risk of a recurrence is low. If a cause was identified, the underlying condition should be treated, and anticoagulant or low-dose aspirin therapy may be initiated, depending on the child's diagnosis.

There is no screening for stroke, but screening exists for many of its risk factors. To prevent stroke, risk factors should be treated and managed by the child's primary care doctor or specialist. The doctor can advise if specific preventive treatment is needed.

Management of high cholesterol—especially high LDL (low-density lipoprotein) levels—high blood pressure and diabetes can help reduce the risk of a stroke.

Nutritional concerns

An adequate intake of folic acid (vitamin B9) has been linked to the prevention of stroke and heart disease by lowering homocysteine, an amino acid related to the early development of cardiovascular disease when high levels are present in the blood. Dietary sources of folic acid include: vegetables, especially green vegetables; potatoes; cereal and cereal products; fruits; and organ meats (liver or kidney). It is best to eat fresh fruits and vegetables whenever possible to get the most vitamins . Recommended daily intake in micrograms (mcg) for folic acid supplements (oral tablets) include: 25–100 mcg in newborns to age three; 75–400 mcg in children aged four to six; 100-400 mcg in children aged seven to 10; and 150–400 mcg in children aged 11 and above.

Vitamin K is an important nutrient needed to regulate normal blood clotting. A diet deficient in vitamin K can cause prolonged blood-clotting time and easy bleeding and bruising. Vitamin K is found in: alfalfa, asparagus, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage cheddar cheese, green tea, green leafy lettuce, liver, seaweed, spinach, and turnip greens. Recommended daily intake for vitamin K supplements (for patients not on anticoagulant therapy) include: 10 mcg in newborns to age three; 20 mcg in children aged four to six; 30 mcg in children aged seven to 14; 65 mcg in boys and 55 mcg in girls aged 15–18; 70–80 mcg for males over age 18 and 60–65 mcg for females over age 18. If the patient is taking anticoagulant medications, vitamin K supplements are not recommended, and foods high in vitamin K are limited, since they counteract the action of the medication.

Vitamin E and beta carotene supplements were once thought to help decrease the risk of stroke and prevent the development of heart disease, but newer studies disprove their effectiveness. Researchers at The Cleveland Clinic Heart Center performed a meta-analysis of seven large randomized trials of vitamin E (given alone or in combination with other antioxidants) and eight of beta carotene. All trials included 1,000 or more patients and follow-up ranged from 1.4 to 12 years. The doses of vitamin E given in these trials ranged from 50–800 international units (IU) and 15–50 milligrams (mg) for beta carotene. The meta-analysis reviewed the effect of these antioxidants on death from cardiovascular disease or from any other cause ("all-cause mortality").

Their findings, published in the June, 2003 issue of The Lancet journal, do not support the continued use of vitamin E supplementation nor the inclusion of vitamin E in further studies. Regardless of the dosage given or the patient population, Vitamin E did not provide any benefit in lowering mortality compared to control treatments, and it did not significantly decrease the risk of cardiovascular death or stroke (cerebrovascular accident). In addition, they recommend that vitamin supplements containing beta carotene be "actively discouraged" because of the small but statistically significant increased risk of death. Researchers discourage further study of beta carotene because of the mortality risk.

Even though studies have demonstrated that vitamin E and beta carotene supplements do not reduce stroke risk, foods rich in antioxidants are still encouraged because they also contain beneficial nutrients such as flavonoids and lycopenes that are not usually included in standard oral vitamin supplements. A diet rich in antioxidant-containing foods, such as fruits, vegetables and whole grains, is linked to a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

Dietary supplements should not be used as a substitute for medical therapies prescribed by a doctor. Parents should discuss these nutrition supplements with the child's doctor to determine the remedies that may be beneficial for the child.

Parental concerns

It is common for a child to feel sad or depressed after a stroke. These emotions may be the result of not knowing what to expect or not being able to do simple tasks without becoming overly tired. Temporary feelings of sadness are normal, and should gradually go away within a few weeks, as the child starts a rehabilitation program and returns to some of his or her normal routines and activities.

When a depressed mood is severe and accompanied by other symptoms that persist every day for two or more weeks, the parent should ask for a referral to a mental health professional who can help the child cope and recover. There are many treatments for depression. A healthy lifestyle including regular exercise, proper sleep , a well-balanced diet, as well as relaxation and stress management techniques can help manage depression. Major depressive disorder may be treated with antidepressants , psychotherapy (supportive counseling or "talk therapy"), or a combination of both.

Regular follow-up visits with the child's health care provider will help identify and manage risk factors and other medical conditions. If the child has a known medical condition that increases the risk of stroke, it is important for parents and caregivers to learn the warning signs and symptoms of stroke in children and infants. If the child experiences any unexpected neurological problem, the parent should have the child evaluated by a physician. Lastly, it is important for parents to carefully follow the child's treatment plan, including following the medication schedule exactly as prescribed.

Resources

BOOKS

Burkman, Kip. The Stroke Recovery Book: A Guide for Patients and Families . Nebraska: Addicus Books, Inc., May, 1998.

Senelick, Richard C., Peter W. Rossi, and Karla Dougherty. Living with Stroke: A Guide For Families: Help and New Hope for All Those Touched by Stroke . New York: McGraw-Hill/Contemporary Books, June, 1999.

Zimmer, Judith and John P. Cooke. The Cardiovascular Cure: How to Strengthen Your Self-Defense Against Heart Attack and Stroke . New York: Broadway Books, August, 2002.

PERIODICALS

Abram, Harry S., MD. "Childhood Strokes: Evaluation and Treatment." Duval County Medical Society. www.dchmsonline.org/jax-medicine/1998journals/november1998/childhoodstrokes.htm.

deVeber, G., ES Roach, AR Riela, and M. Wiznitzer. "Stroke in Children: Recognition, Treatment, and Future Directions." Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 7:4 (December, 2000): 309-317.

deVeber, G., ES Roach, AR Riela, and M. Wiznitzer. "Recognition and Treatment of Stroke in Children." Child Neurology Society Ad Hoc Committee on Stroke in Children. July, 2001.

Kirkham, FJ. "Stroke in Childhood." Archives of Disease in Childhood. 81 (July, 1999): 85-89.

Nicolaides, P. and R.E. Appleton. "Stroke in Children." Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 38:2 (February, 1996): 172-180.

ORGANIZATIONS

American Stroke Foundation. 11902 Lowell, Overland Park, KS 66213. (913) 649-1776. http://www.americanstroke.org .

KEY TERMS

Activities of daily living (ADL) —The activities performed during the course of a normal day, for example, eating, bathing, dressing, toileting, etc.

Aneurysm —A weakened area in the wall of a blood vessel which causes an outpouching or bulge. Aneurysms may be fatal if these weak areas burst, resulting in uncontrollable bleeding.

Anoxia —Lack of oxygen.

Antibody —A special protein made by the body's immune system as a defense against foreign material (bacteria, viruses, etc.) that enters the body. It is uniquely designed to attack and neutralize the specific antigen that triggered the immune response.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome —An immune disorder that occurs when the body recognizes phospholipids (part of a cell's membrane) as foreign and produces abnormal antibodies against them. This syndrome is associated with abnormal blood clotting, low blood platelet counts, and migraine headaches.

Aorta —The main artery located above the heart that pumps oxygenated blood out into the body. The aorta is the largest artery in the body.

Aortic valve —The valve between the heart's left ventricle and ascending aorta that prevents regurgitation of blood back into the left ventricle.

Aortic valve stenosis —Narrowing of the aortic valve.

Aphasia —The loss of the ability to speak, or to understand written or spoken language. A person who cannot speak or understand language is said to be aphasic.

Arteriosclerosis —A chronic condition characterized by thickening, loss of leasticity, and hardening of the arteries and the build-up of plaque on the arterial walls. Arteriosclerosis can slow or impair blood circulation. It includes atherosclerosis, but the two terms are often used synonymously.

Artery —A blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart to the cells, tissues, and organs of the body.

Atrial —Referring to the upper chambers of the heart.

Atrial fibrillation —A type of heart arrhythmia in which the upper chamber of the heart quivers instead of pumping in an organized way. In this condition, the upper chambers (atria) of the heart do not completely empty when the heart beats, which can allow blood clots to form.

Atrial septal defect —An opening between the right and left atria (upper chambers) of the heart.

Cardiologist —A physician who specializes in diagnosing and treating heart diseases.

Central nervous system —Part of the nervous system consisting of the brain, cranial nerves, and spinal cord. The brain is the center of higher processes, such as thought and emotion and is responsible for the coordination and control of bodily activities and the interpretation of information from the senses. The cranial nerves and spinal cord link the brain to the peripheral nervous system, that is the nerves present in the rest of body.

Cerebrospinal fluid —The clear, normally colorless fluid that fills the brain cavities (ventricles), the subarachnoid space around the brain, and the spinal cord and acts as a shock absorber.

Decompression —A decrease in pressure from the surrounding water that occurs with decreasing diving depth.

Dysphagia —Difficulty in swallowing.

Echocardiogram —A record of the internal structures of the heart obtained from beams of ultrasonic waves directed through the wall of the chest.

Electrocardiagram (ECG, EKG) —A record of the electrical activity of the heart, with each wave being labeled as P, Q, R, S, and T waves. It is often used in the diagnosis of cases of abnormal cardiac rhythm and myocardial damage.

Embolus —Plural, emboli. An embolus is something that blocks the blood flow in a blood vessel. It may be a gas bubble, a blood clot, a fat globule, a mass of bacteria, or other foreign body that forms somewhere else and travels through the circulatory system until it gets stuck.

Encephalitis —Inflammation of the brain, usually caused by a virus. The inflammation may interfere with normal brain function and may cause seizures, sleepiness, confusion, personality changes, weakness in one or more parts of the body, and even coma.

Graft —A transplanted organ or other tissue.

Heart attack —Damage that occurs to the heart when one of the coronary arteries becomes narrowed or blocked.

Hemiparesis —Weakness on one side of the body.

Hemiplegia —Paralysis of one side of the body.

Hydrocephalus —An abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid within the brain. This accumulation can be harmful by pressing on brain structures, and damaging them.

Hypercoagulable states —Also called thromboembolic state or thrombophilia. A condition characterized by excess blood clotting.

Hypertension —Abnormally high arterial blood pressure, which if left untreated can lead to heart disease and stroke.

Intracerebral hemorrhage —A cause of some strokes in which vessels within the brain begin bleeding.

Ischemia —A decrease in the blood supply to an area of the body caused by obstruction or constriction of blood vessels.

Mitral valve stenosis —Narrowing of the mitral valve.

Neurologist —A doctor who specializes in disorders of the nervous system, including the brain, spinal cord, and nerves.

Neurosurgeon —Physician who performs surgery on the nervous system.

Occupational therapist —A healthcare provider who specializes in adapting the physical environment to meet a patient's needs. An occupational therapist also assists patients and caregivers with activities of daily living and provide instructions on wheelchair use or other adaptive equipment.

Patent ductus arteriosus —A congenital defect in which the temporary blood vessel connecting the left pulmonary artery to the aorta in the fetus doesn't close after birth.

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) —A congenital heart defect characterized by an open flap that remains between the two upper chambers of the heart (the left and right atria). This opening can allow a blood clot from one part of the body to travel through the flap and up to the brain, causing a stroke.

Physiatrist —A physician who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Physical therapist —A healthcare provider who teaches patients how to perform therapeutic exercises to maintain maximum mobility and range of motion.

Reye's syndrome —A serious, life-threatening illness in children, usually developing after a bout of flu or chickenpox, and often associated with the use of aspirin. Symptoms include uncontrollable vomiting, often with lethargy, memory loss, disorientation, or delirium. Swelling of the brain may cause seizures, coma, and in severe cases, death.

Stent —A slender hollow catheter or rod placed within a vessel or duct to provide support or to keep it open.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage —A collection of blood in the subarachnoid space, the space between the arachnoid and pia mater membranes that surround the brain. This space is normally filled with cerebrospinal fluid. A subarachnoid hemorrhage can lead to stroke, seizures, permanent brain damage, and other complications.

Unilateral neglect —Also called one-sided neglect. A side effect of stroke in which the stroke survivor ignores or forgets the weaker side of the body caused by the stroke.

Vein —A blood vessel that returns blood to the heart from the body. All the veins from the body converge into two major veins that lead to the right atrium of the heart. These veins are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava. The pulmonary vein carries the blood from the right ventricle of the heart into the lungs.

Ventricle septal defect —A hole in the wall (septum) between the lower chambers of the heart.

Ventricles —The lower pumping chambers of the heart. The ventricles push blood to the lungs and the rest of the body.

Ventricles of the brain —The spaces within the brain where cerebrospinal fluid is made.

American Stroke Association, A Division of American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Ave., Dallas, TX 75231. (888) 4-STROKE (787653). E-mail: strokeassociation@heart.org. http://www.strokeassociation.org .

Children's Hemiplegia and Stroke Association. 4101 W. Green Oaks, Ste. 305, PMB 149, Arlington, TX 76016. (817) 492-4325. E-mail: info@chasa.org. http://www.chasa.org .

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. National Institutes of Health, Building 1, 1 Center Dr., Bethesda, MD 20892. E-mail: NHLBIinfo@rover.nhlbi. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov .

National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, U.S. Department of Education, 400 Maryland Ave. S.W., Washington, DC 20202-7100. (202) 245-7640. http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/nidrr/ .

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health. P.O. Box 5801, Bethesda, MD 20824. (800) 352-9424 or (301) 496-5751. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/about_ninds/ .

National Rehabilitation Information Center (NARIC).4200 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 202, Lanham, MD 20700. (800) 346-2742 or (301) 459-5900. http://www.naric.com .

National Stroke Association. 9707 E. Easter Ln., Englewood, CO 80112-3747. (800) STROKES (787-6537) or (303) 649-9299. http://www.stroke.org .

Stroke Clubs International. 805 12th St. Galveston, TX 77550. (409) 762-1022 attn. Ellis Williamson. E-mail: strokeclub@aol.com.

WEB SITES

The Brain Attack Coalition. http://www.stroke-site.org

The Brain Matters , American Academy of Neurology Foundation. http://www.thebrainmatters.org

Different Strokes—A Charity for Younger Stroke Survivors . http://www.differentstrokes.co.uk/

HeartCenterOnline . http://www.heartcenteronline.com

HemiHelp—Information and Support for Children and Young People with Hemiplegia . http://www.hemihelp.org.uk

Pediatric Stroke Network . http://www.pediatricstrokenetwork.com

Angela M. Costello

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: