Marfan syndrome

Definition

Marfan syndrome is an inherited disorder of the connective tissue that causes abnormalities of a child's eyes, cardiovascular system, and musculoskeletal system. It is named for the French pediatrician, Antoine Marfan (1858-1942), who first described it in 1896.

Description

Marfan syndrome affects three major organ systems of the body: the heart and circulatory system, the bones and muscles, and the eyes. The genetic mutation responsible for Marfan was discovered in 1991. It affects the body's production of fibrillin, which is a protein that is an important part of connective tissue. Fibrillin is the primary component of the microfibrils that allow tissues to stretch repeatedly without weakening. Because the child's fibrillin is abnormal, his or her connective tissues are looser than usual, which weakens or damages the support structures of the entire body.

The most common external signs associated with Marfan syndrome include excessively long arms and legs, with the child's arm span being greater than his or her height. The fingers and toes may be long and slender, with loose joints that can be bent beyond their normal limits. This unusual flexibility is called hypermobility. The child's face may also be long and narrow, and he or she may have a noticeable curvature of the spine. It is important to note, however, that children with Marfan vary widely in the external signs of their disorder and in their severity; even two children from the same family may look quite different. Most of the external features of Marfan syndrome become more pronounced as the child gets older, so that diagnosis of the disorder is often easier in adults than in children. In many cases, the child may have few or very minor outward signs of the disorder, and the diagnosis may be missed until the child develops vision problems or cardiac symptoms.

Marfan syndrome by itself does not affect a child's intelligence or ability to learn. There is, however, some clinical evidence that children with Marfan have a slightly higher rate of hyperactivity and attention-deficit disorder (ADD) than the general population. In addition, a child with undiagnosed nearsightedness related to Marfan may have difficulty seeing the blackboard or reading printed materials, and thus do poorly in school.

Marfan syndrome affects males and females equally, and appears to be distributed equally among all races and ethnic groups. The rate of mutation of the fibrillin gene, however, appears to be related to the age of the child's father; older fathers are more likely to have new mutations appear in chromosome 15.

Marfan syndrome is sometimes called arachnodactyly, which means "spider-like fingers" in Greek, since one of the characteristic signs of the disease is disproportionately long fingers and toes.

Demographics

It is estimated that one person in every 3000-5000 has Marfan syndrome, or about 50,000 people in the United States. Marfan syndrome is one of the more common inheritable disorders.

Causes and symptoms

Marfan syndrome is caused by a single gene for fibrillin on chromosome 15, which is inherited in most cases from an affected parent. Between 15 and 25 percent of cases result from spontaneous mutations. Mutations of the fibrillin gene (FBNI) are unique to each family affected by Marfan, which makes rapid genetic diagnosis impossible, given present technology. The syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder, which means that someone who has it has a 50 percent chance of passing it on to any offspring.

Another important genetic characteristic of Marfan syndrome is variable expression. This term means that the mutated fibrillin gene can produce a variety of symptoms of very different degrees of severity, even in members of the same family.

Cardiac and circulatory abnormalities

The most important complications of Marfan are those affecting the heart and major blood vessels; some are potentially life-threatening. About 90 percent of children with Marfan will develop cardiac complications, including:

- Aortic enlargement. This is the most serious potential complication of Marfan syndrome. Because of the abnormalities of the child's fibrillin, the walls of the aorta (the large blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart) are weaker than normal and tend to stretch and bulge out of shape. This stretching increases the likelihood of an aortic dissection, which is a tear or separation between the layers of tissue that make up the aorta. An aortic dissection usually causes severe pain in the abdomen, back, or chest, depending on the section of the aorta that is affected. Rupture of the aorta is a medical emergency requiring immediate surgery and medication.

- Aortic regurgitation. A weakened and enlarged aorta may allow some blood to leak back into the heart during each heartbeat; this condition is called aortic regurgitation. Aortic regurgitation occasionally causes shortness of breath during normal activity. In serious cases, it causes the left ventricle of the heart to enlarge and may eventually lead to heart failure.

- Mitral valve prolapse. Between 75 and 85% of children with Marfan have loose or "floppy" mitral valves, which are the valves that separate the chambers of the heart. When these valves do not cover the opening between the chambers completely, the condition is called mitral valve prolapse. Complications of mitral valve prolapse include heart murmurs and arrhythmias. In rare cases, mitral valve prolapse can cause sudden death.

- Infective endocarditis. Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endothelium, the tissue that lines the heart. In children with Marfan, it is the abnormal mitral valve that is most likely to become infected.

- Other complications. Some children with Marfan develop cystic disease of the lungs or recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax, which is a condition in which air accumulates in the space around the lungs. Many will also eventually develop emphysema.

Musculoskeletal abnormalities

Marfan syndrome causes an increase in the length of the child's bones, with decreased support from the ligaments that hold the bones together. As a result, the child may develop various deformities of the skeleton or disorders related to the relative looseness of the ligaments.

Disorders of the spine

Children with Marfan syndrome also can experience spinal disorders, including:

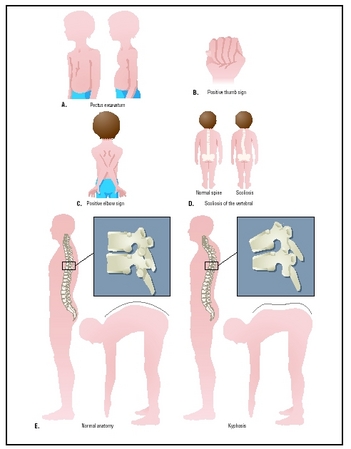

- Scoliosis . Scoliosis, or curvature of the spine, is a disorder in which the vertebrae that make up the spine twist out of line from side to side into an S-shape or a spiral. It is caused by a combination of the rapid growth of children with Marfan, and the looseness of the ligaments that help the spine to keep its shape.

- Kyphosis. Kyphosis is an abnormal outward curvature of the spine at the back, sometimes called hunch back when it occurs in the upper back. Children with Marfan may develop kyphosis either in the upper (thoracic) spine or the lower (lumbar) spine.

- Spondylolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis is the medical term for a forward slippage of one vertebra on the one below it. It produces an ache or stiffness in the lower back.

- Dural ectasia. The dura is the tough, fibrous outermost membrane covering the brain and the spinal cord. The weak dura in a child with Marfan swells or bulges under the pressure of the spinal fluid. This swelling is called ectasia. In most cases, dural ectasia occurs in the lower spine, producing low back ache, a burning feeling, or numbness or weakness in the legs.

Disorders of the chest and lower body

Disorders of the chest and lower body of children with Marfan include:

- Pectus excavatum. Pectus excavatum is a malformation of the chest in which the child's breastbone, or sternum, is sunken inward. It can cause difficulties in breathing, especially if the heart, spine, and lung have been affected by Marfan. It also usually causes concerns about appearance.

- Pectus carinatum. In other children with Marfan, the sternum is pushed outward and narrowed. Although pectus carinatum does not cause breathing difficulties, it can cause embarassment about appearance. A few children with Marfan may have a pectus excavatum on one side of their chest and a pectus carinatum on the other.

- Foot disorders. Children with Marfan are more likely to develop pes planus (flat feet) or so-called "claw" or "hammer" toes than people in the general population. They are also more likely to suffer from chronic pain in their feet.

- Protrusio acetabulae. The acetabulum is the socket of the hip joint. In a child with Marfan, the acetabulum becomes deeper than normal during growth, for reasons that are not yet understood. Although protrusio acetabulae does not cause problems during childhood and adolescence , it can lead to a painful form of arthritis in adult life.

Disorders of the eyes and face

Although the visual problems that are related to Marfan syndrome are rarely life-threatening, they are important in that they may be the child's first indication of the disorder. Eye disorders related to the syndrome include the following:

- Myopia (nearsightedness). Most children with Marfan develop nearsightedness, usually in childhood.

- Ectopia lentis. Ectopia lentis is the medical term for dislocation of the lens of the eye. Between 65 and 75 percent of children with Marfan have dislocated lenses. This condition is an important indication for diagnosis of the syndrome because there are relatively few other disorders that produce it.

- Glaucoma. This condition is much more prevalent in children with Marfan syndrome than in the general population.

- Cataracts. Children with Marfan are more likely to develop cataracts, and to develop them much earlier in life, sometimes as early as 40 years of age.

- Retinal detachment. Children with Marfan are more vulnerable to this disorder because of the weakness of their connective tissues. Untreated retinal detachment can cause blindness. The danger of retinal detachment is an important reason for children to avoid contact sports or other activities that could cause a blow on the head or being knocked to the ground.

- Other facial problems. Children with Marfan sometimes develop dental problems related to crowding of the teeth caused by a high-arched palate and a narrow jaw.

Other disorders

Other disorders associated with Marfan syndrome include:

- Striae. Striae are stretch marks in the skin caused by rapid weight gain or growth; they frequently occur in pregnant women, for example. Children with Marfan often develop striae over the shoulders, hips, and lower back at an early age because of rapid bone growth. Although the child may be self-conscious about the striae, they are not a danger to health.

- Obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea refers to partial obstruction of the airway during sleep, causing irregular breathing and sometimes snoring. In children with Marfan, obstructive sleep apnea is caused by the unusual flexibility of the tissues lining the child's airway. This disturbed breathing pattern increases the risk of aortic dissection.

When to call the doctor

Prospective parents with a family history of Marfan syndrome should check with their doctor concerning genetic counseling. Also a doctor should be called if a child has symptoms suggestive of Marfan syndrome.

Diagnosis

Presently, there is no objective diagnostic test for Marfan syndrome, in part because the disorder does not produce any measurable biochemical changes in the child's blood or body fluids, or cellular changes that can be detected from a tissue sample. Although researchers in molecular biology are currently investigating the FBNI gene through a process called mutational analysis, it is presently not useful as a diagnostic test because there is evidence that there can be mutations in the fibrillin gene that do not produce Marfan. Similarly, there is no reliable prenatal test, although some physicians have used ultrasound to try to determine the length of fetal limbs in at-risk pregnancies.

The diagnosis is made by taking a family history and a thorough examination of the child's eyes, heart, and bone structure. The examination should include an echocardiogram taken by a cardiologist, a slit-lamp eye examination by an ophthalmologist, and a work-up of the child's spinal column by an orthopedic specialist. In terms of the cardiac examination, a standard electrocardiogram (EKG) is not sufficient for diagnosis; only the echocardiogram can detect possible enlargement of the aorta. The importance of the slit-lamp examination is that it allows the doctor to detect a dislocated lens, which is a significant indication of the syndrome.

The symptoms of Marfan syndrome in some children resemble the symptoms of homocystinuria, which is an inherited disorder marked by extremely high levels of homocystine in the child's blood and urine. This possibility can be excluded by a urine test.

In other cases, the diagnosis remains uncertain because of the mildness of the child's symptoms, the absence of a family history of the syndrome, and other variables. These borderline conditions are sometimes referred to as marfanoid syndromes.

Treatment

The treatment and management of Marfan is tailored to the specific symptoms of each child. Some children find that the syndrome has little impact on their overall lifestyle; others have found their lives centered on the disorder.

Cardiovascular system

After a child has been diagnosed with Marfan, he or she should be monitored with an echocardiogram every six months until it is clear that the aorta is not growing larger. After that, he or she should have an echocardiogram once a year. If the echocardiogram does not allow the physician to visualize all portions of the aorta, CT ( computed tomography ) or MRI ( magnetic resonance imaging ) may be used. In cases involving a possible aortic dissection, the child may be given a TEE (transesophageal echocardiogram).

Medications. A child with Marfan may be given drugs called beta-blockers to slow down the rate of aortic enlargement and decrease the risk of dissection by lowering the blood pressure and decreasing the forcefulness of the heartbeat. The most commonly used beta-blockers in chidren with Marfan are propranolol (Inderal) and atenolol (Tenormin). Children who are allergic to beta-blockers may be given a calcium blocker such as verapamil.

Because children with Marfan are at increased risk for infective endocarditis, they must take a prophylactic dose of an antibiotic before having dental work or minor surgery, as these procedures may allow bacteria to enter the bloodstream. Penicillin and amoxicillin are the antibiotics most often used.

Surgical treatment. Surgery may be necessary if the width of the child's aorta increases rapidly or reaches a critical size (about 2 inches [5 cm]). The most common surgical treatment involves replacing the child's aortic valve and several inches of the aorta itself with a composite graft, which is a prosthetic heart valve sewn into one end of a Dacron tube. This surgery has been performed widely since about 1985; most children who have had a composite graft have not needed additional surgery. Children who have had a valve replaced must take an anticoagulant medication, usually warfarin (Coumadin), in order to minimize the possibility of a clot forming on the prosthetic valve.

Musculoskeletal system

Children diagnosed with Marfan should be checked for scoliosis by their pediatricians at each annual physical examination. The doctor simply asks the child to bend forward while the back is examined for changes in the curvature. In addition, the child's spine should be x rayed in order to measure the extent of scoliosis or kyphosis. The curve is measured in degrees by the angle between the vertebrae as seen on the x ray. Curves of 20 degrees or less are not likely to become worse. Curves between 20 and 40

Scoliosis between 20 and 40 degrees in children is usually treated with a back brace. The child must wear this appliance about 23 hours a day until growth is complete. If the spinal curvature increases to 40 or 50 degrees, the child may require surgery in order to prevent lung problems, back pain, and further deformity. Surgical treatment of scoliosis involves straightening the spine with metal rods and fusing the vertebrae in the straightened position.

Spondylolisthesis is treated with a brace in mild cases. If the slippage is more than 30 degrees, the slipped vertebra may require surgical realignment.

Dural ectasia can be distinguished from other causes of back pain on an MRI. Mild cases are usually not treated. Medication or spinal shunting to remove some of the spinal fluid are used to treat severe cases.

Pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum can be treated by surgery. In pectus excavatum, the deformed breastbone and ribs are raised and straightened by a metal bar. After four to six months, the bar is removed in an outpatient procedure.

Protrusio acetabulae may require artificial hip joint surgery in adult life, if the arthritic pains are severe.

Pain in the feet or limbs is usually treated with a mild analgesic such as acetaminophen . Children with Marfan should consider wearing shoes with low heels, special cushions, or orthotic inserts. Foot surgery is rarely necessary.

Visual and dental concerns

Children with Marfan should have a thorough eye examination, including a slit-lamp examination, to test for dislocation of the lens as well as nearsightedness. Dislocation can be treated by a combination of special glasses and daily use of one percent atropine sulfate ophthalmic drops, or by surgery.

Because children with Marfan are at increased risk of glaucoma, they should have the fluid pressure inside the eye measured every year as part of an eye examination. Glaucoma can be treated with medications or with surgery.

Cataracts are treated with increasing success by implant surgery. It is important, however, to seek treatment at medical centers with eye surgeons familiar with the possible complications of cataract surgery in children with Marfan syndrome.

All children with Marfan should be taught to recognize the signs of retinal detachment (sudden blurring of vision in one eye becoming progressively worse without pain or redness) and ask their parents to seek professional help immediately.

Children with Marfan should be evaluated by their dentist at each checkup for crowding of the teeth and possible misalignment and referred to an orthodontist if necessary.

Athletic activities and occupational choice

Children with Marfan should avoid sports or occupations that require heavy weight lifting, rough physical contact, or rapid changes in atmospheric pressure (e.g., scuba diving). Weight lifting increases blood pressure, which in turn may enlarge the aorta. Rough physical contact may cause retinal detachment. Sudden changes in air pressure may produce pneumothorax. Regular noncompetitive physical exercise , however, is beneficial for children with Marfan. Good choices include brisk walking, shooting baskets, and slow-paced tennis.

KEY TERMS

Arachnodactyly —A condition characterized by abnormally long and slender fingers and toes.

Ectopia lentis —Dislocation of the lens of the eye. It is one of the most important single indicators in diagnosing Marfan syndrome.

Fibrillin —A protein that is an important part of the structure of the body's connective tissue. In Marfan's syndrome, the gene responsible for fibrillin has mutated, causing the body to produce a defective protein.

Hypermobility —Unusual flexibility of the joints, allowing them to be bent or moved beyond their normal range of motion.

Kyphosis —An extreme, abnormal outward curvature of the spine, with a hump at the upper back.

Pectus carinatum —An abnormality of the chest in which the sternum (breastbone) is pushed outward. It is sometimes called "pigeon breast."

Pectus excavatum —An abnormality of the chest in which the sternum (breastbone) sinks inward; sometimes called "funnel chest."

Scoliosis —An abnormal, side-to-side curvature of the spine.

Social and lifestyle issues

Smoking is particularly harmful for children and adolescents with Marfan because it increases their risk of emphysema.

Children and adolescents with Marfan may benefit from supportive counseling regarding appearance, particularly if their symptoms are severe enough to cause them to withdraw from social activities.

Prognosis

The prognosis for children with Marfan has improved markedly in recent years. By 1995, the life expectancy of people with the syndrome increased to 72 years, up from 48 years in 1972. This dramatic improvement is attributed to new surgical techniques, improved diagnosis, and new techniques of medical treatment.

The most important single factor in improving the child's prognosis is early diagnosis. The earlier that a child can benefit from the new techniques and lifestyle modifications, the more likely he or she is to have a longer life expectancy.

Prevention

Marfan syndrome that occurs because of spontaneous new mutations (15% to 25% of the cases) cannot be prevented. However, for prospective parents with a family history of Marfan syndrome, genetic counseling is recommended. Also, older fathers are more likely to have new mutations appear in chromosome 15.

Parental concerns

Families may wish to seek counseling regarding the effects of the syndrome on relationships within the family. Many people respond with guilt, fear , or blame when a genetic disorder is diagnosed in the family, or they may overprotect the affected member. Support groups are often good sources of information about Marfan; they can offer helpful suggestions about living with it as well as emotional support.

Resources

BOOKS

Marfan Syndrome: A Medical Dictionary, Bibliography, and Annotated Research Guide to Internet References. San Diego, CA: Icon Health Publications, 2004.

The Official Patient's Sourcebook on Klinefelter Syndrome. San Diego, CA: Icon Health Publications, 2002.

PM Medical Health News. 21st Century Complete Medical Guide to Marfan Syndrome: Authoritative Government Documents, Clinical References, and Practical Information for Patients and Physicians. CD-ROM. Washington, DC: Progressive Management, 2004.

Pyeritz, Reed E., and Cheryll Gasner. The Marfan Syndrome. New York: National Marfan Syndrome, 1999.

Robinson, Peter. Marfan Syndrome. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004.

ORGANIZATIONS

Alliance of Genetic Support Groups, 4301 Connecticut Avenue, Washington, DC, 20008. (202) 652-5553. http://http:www.geneticalliance.org.

National Marfan Foundation, 22 Manhasset Avenue, Port Washington, NY, 11050-2023. (516) 883-8712, (800). 862-7326. http://http:www.marfan.org.

WEB SITES

Marfan Syndrome, National Institutes of Health. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/marfansyndrome.html .

Judith Sims, MS Rebecca J. Frey, PhD

Thank you very much.