Juvenile arthritis

Definition

Juvenile arthritis (JA) refers to a number of different conditions, all of which strike children and all of which have joint inflammation as their major manifestation. The condition is also referred to as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Description

The skeletal system of the body is made up of different types of the strong, fibrous tissue known as connective tissue. Bone, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons are all forms of connective tissue which have different compositions and different characteristics.

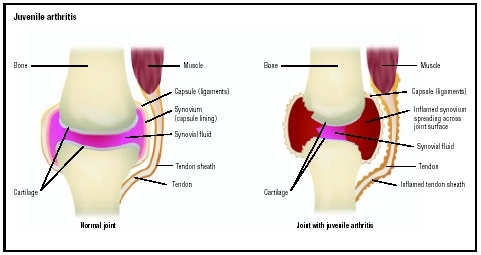

The joints are structures that hold two or more bones together. Some joints (synovial joints) allow for movement between the bones being joined (called articulating bones). The simplest model of a synovial joint involves two bones, separated by a slight gap called the joint cavity. The ends of each articular bone are covered by a layer of cartilage. Both articular bones and the joint cavity are surrounded by a tough tissue called the articular capsule. The articular capsule has two components: the fibrous membrane on the outside and the synovial membrane (or synovium) on the inside. The fibrous membrane may include tough bands of fibrous tissue called ligaments, which are responsible for providing support to the joints. The synovial membrane has special cells and many capillaries (tiny blood vessels). This membrane produces a supply of synovial fluid which fills the joint cavity, lubricates it, and helps the articular bones move smoothly about the joint.

In JA, the synovial membrane becomes intensely inflamed. Usually thin and delicate, the synovium becomes thick and stiff, with numerous infoldings on its surface. The membrane becomes invaded by white blood cells, which produce a variety of destructive chemicals. The cartilage along the articular surfaces of the bones may be attacked and destroyed, and the bone, articular capsule, and ligaments may begin to be worn away (eroded). These processes severely interfere with movement in the joint.

JA specifically refers to chronic arthritic conditions which affect a child under the age of 16 years and which last for a minimum of three to six months. JA is often characterized by a waxing and waning course, with flares separated by periods during which no symptoms are noted (remission). Some literature refers to JA as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, although most types of JA differ significantly from the adult disease called rheumatoid arthritis, in terms of symptoms, progression, and prognosis.

Demographics

Between five and 18 of every 100,000 children develop juvenile rheumatoid arthritis each year; the overall prevalence is approximately 30–150 per 100,000. More than 65,000 young people in the United States develop it each year. It can affect children as young as two years of age.

Causes and symptoms

A number of different causes have been sought to explain the onset of JA. There seems to be some genetic link, based on the fact that the tendency to develop JA sometimes runs in a particular family and based on the fact that certain genetic markers are more frequently found in patients with JA and other related diseases. Many researchers have looked for some infectious cause for JA, but no clear connection to a particular organism had been made as of 2004. JA is considered by some to be an autoimmune disorder. Autoimmune disorders occur when the body's immune system mistakenly identifies the body's own tissue as foreign and goes about attacking those tissues, as if trying to rid the body of an invader (such as a bacteria, virus, or fungi). While an autoimmune mechanism is strongly suspected, certain markers of such a mechanism (such as rheumatoid factor, often present in adults with such disorders) are rarely present in children with JA.

Joint symptoms of arthritis may include stiffness, pain , redness and warmth of the joint, and swelling. Bone in the area of an affected joint may grow too quickly or too slowly resulting in limbs which are of different lengths. When the child tries to avoid moving a painful joint, the muscle may begin to shorten from disuse. This condition is called a contracture.

Symptoms of JA depend on the particular subtype. JA is classified by the symptoms which appear within the first six months of the disorder:

- Pauciarticular JA: The most common and the least severe type of JA affects about 40–60 percent of all JA patients. This type of JA affects fewer than four joints, usually the knee, ankle, wrist, and/or elbow. Other more general (systemic) symptoms are usually absent, and the child's growth usually remains normal. Very few children (fewer than 15 percent) with pauciarticular JA end up with deformed joints. Some children with this form of JA experience painless swelling of the joint. Some children with JA have a serious inflammation of structures within the eye, which if left undiagnosed and untreated could even lead to blindness. While many children have cycles of flares and remissions, in some children the disease completely and permanently resolves within a few years of diagnosis.

-

Polyarticular JA: About 40 percent of all cases of JA are of this type.

More girls than boys are diagnosed with this form of JA, and it is most

common in children up to age three or after the age of ten.

Polyarticular JA affects five or more joints simultaneously. This type

of JA usually affects the small joints of both hands and both feet,

although other large joints may be affected as well. Some patients with

arthritis in their knees will experience a different rate of growth in

each leg. Ultimately, one leg will grow longer than the other. About

half of all patients with polyarticular JA have arthritis of the spine

and/or hip. Some patients with polyarticular JA will have other symptoms

of a systemic illness, including anemia (low red blood cell count),

decreased growth rate, low appetite, low-grade

fever

, and a slight rash. The disease is most severe in those children who

are diagnosed in early

adolescence

. Some of these children test positive for a marker present in other

autoimmune disorders, called rheumatoid factor (RF), which is found in

adults who have rheumatoid

arthritis. Children who are positive for RF tend to have a more severe course, with a disabling form of arthritis that destroys and deforms the joints. This type of arthritis is thought to be the adult form of rheumatoid arthritis occurring at a very early age.

Normal knee joint (left) and one affected by juvenile arthritis, which shows damaged cartilage and inflammation of the synovial fluid and tendon sheath.(Illustration by GGS Information Services.)

Normal knee joint (left) and one affected by juvenile arthritis, which shows damaged cartilage and inflammation of the synovial fluid and tendon sheath.(Illustration by GGS Information Services.) - Systemic onset JA: Sometimes called Still disease (after a physician who originally described it), this type of JA occurs in about 10–20 percent off all patients with JA. Boys and girls are equally affected, and diagnosis is usually made between the ages of five and 10 years. The initial symptoms are not usually related to the joints. Instead, these children have high fevers; a rash; decreased appetite and weight loss; severe joint and muscle pain; swollen lymph nodes, spleen, and liver; and serious anemia. Some children experience other complications, including inflammation of the sac containing the heart (pericarditis); inflammation of the tissue lining the chest cavity and lungs (pleuritis); and inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis). The eye inflammation often seen in pauciarticular JA is uncommon in systemic onset JA. Symptoms of actual arthritis begin later in the course of systemic onset JA, and they often involve the wrists and ankles. Many of these children continue to have periodic flares of fever and systemic symptoms throughout childhood. Some children go on to develop a polyarticular type of JA.

- Spondyloarthropathy: This type of JA most commonly affects boys older than eight years of age. The arthritis occurs in the knees and ankles, moving over time to include the hips and lower spine. Inflammation of the eye may occur occasionally but usually resolves without permanent damage.

- Psoriatic JA: This type of arthritis usually shows up in fewer than four joints but goes on to include multiple joints (appearing similar to polyarticular JA). Hips, back, fingers, and toes are frequently affected. A skin condition called psoriasis accompanies this type of arthritis. Children with this type of JA often have pits or ridges in their fingernails. The arthritis usually progresses to become a serious, disabling problem.

When to call the doctor

A pediatrician, family physician, or other primary care doctor frequently manages the treatment of a child with JA, often with the help of other doctors. Depending on the patient's and parents' wishes and the severity of the disease, the team of doctors may include pediatric rheumatologists (doctors specializing in childhood arthritis), ophthalmologists (eye doctors), orthopaedic surgeons (bone specialists), and physiatrists (rehabilitation specialists), as well as physical and occupational therapists. The main goals of treatment are to preserve a high level of physical and social functioning and maintain a good quality of life. To achieve these goals, doctors recommend treatments to reduce swelling; maintain full movement in the affected joints; relieve pain; and identify, treat, and prevent complications. Most children with JA need medication and physical therapy to reach these goals.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of JA is often made on the basis of the child's collection of symptoms. Laboratory tests often show normal results. Some nonspecific indicators of inflammation may be elevated, including white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a marker called C-reactive protein. As with any chronic disease, anemia may be noted. Children with an extraordinarily early onset of the adult type of rheumatoid arthritis have a positive test for rheumatoid factor.

Treatment

Treating JA involves efforts to decrease the amount of inflammation in order to preserve movement. Medications which can be used for this include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (such as ibuprofen and naproxen). Oral (by mouth) steroid medications are effective but have many serious side effects with long-term use. Injections of steroids into an affected joint can be helpful. Steroid eye drops are used to treat eye inflammation. Other drugs that have been used to treat JA include methotrexate, sulfasalazine, penicillamine, and hydroxychloroquine. Physical therapy and exercises are often recommended in order to improve joint mobility and to strengthen supporting muscles. Occasionally, splints are used to rest painful joints and to try to prevent or reduce deformities.

Alternative treatment

Alternative treatments that have been suggested for arthritis include juice therapy, which can work to detoxify the body, helping to reduce JA symptoms. Some recommended fruits and vegetables to include in the juice are carrots, celery, cabbage, potatoes, cherries, lemons, beets, cucumbers, radishes, and garlic. However, for children with osteoarthritis, citrus fruits and vegetables from the nightshade family, including potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant, should be avoided since they can promote swelling. As an adjunct therapy, aromatherapy preparations use cypress, fennel, and lemon. Massage oils include rosemary, benzoin, chamomile, camphor, juniper, and lavender. Other types of therapy that have been used for JA include acupuncture, acupressure, and bodywork. Nutritional supplements that may be beneficial

Nutritional concerns

When female patients were compared to agematched normals, greater than one serving per week of grilled (broiled) or baked fish (other than tuna) was associated with a decreased risk of disease. This inverse association was stronger than that for omega-3 fatty acid intake alone. In another study, patients with active disease randomly received treatment with or without a diet in which the energy consumption was adjusted to normal standards for body-weight, and the intake of fish and antioxidants was increased. After six months, those following the diet demonstrated significant improvement in the duration of morning stiffness, the number of swollen joints, and pain status.

Several studies, some of which were controlled, have found beneficial effects from a vegetarian or vegan diet. In one study, for example, patients randomly received either an uncooked vegan diet or a control diet for three months. Those on the vegan diet experienced subjective relief of rheumatic stiffness and joint swellings and an improvement in general wellbeing. After returning to the meat diet, these symptoms worsened. The degree of tender joints remained unchanged in controls, but in the diet group their number decreased significantly.

Prognosis

The prognosis for pauciarticular JA is quite good, as is the prognosis for spondyloarthropathy. Polyarticular JA carries a slightly worse prognosis. RF-positive polyarticular JA carries a difficult prognosis, often with progressive, destructive arthritis and joint deformities. Systemic onset JA has a variable prognosis, depending on the organ systems affected and the progression to polyarticular JA. About 1–5 percent of all JA patients die of such complications as infection, inflammation of the heart, or kidney disease.

Prevention

Because so little is known about what causes JA, there are no recommendations available for ways to avoid developing it.

Parental concerns

JA affects the entire family who must cope with the special challenges of this disease. JA can strain a child's participation in social and after-school activities and make schoolwork more difficult. There are several things that family members can do to help the child do well physically and emotionally. These include the following:

KEY TERMS

Articular bones —Two or more bones that are connected to each other via a joint.

Joint —The connection point where two bones meet.

Synovial joint —A fully moveable joint in which a synovial cavity is present between two articulating bones. Also called a diarthrosis.

Synovial membrane —The membrane that lines the inside of the articular capsule of a joint, and produces a lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

- Ensure that the child receives appropriate medical care and follows the doctor's instructions. Many treatment options are available, and because JA is different in each child, what works for one may not work for another. If the medications that the doctor prescribes do not relieve symptoms or if they cause unpleasant side effects, patients and parents should discuss other choices with their doctor. A person with JA can be more active when symptoms are controlled.

- Encourage exercise and physical therapy for the child. For many young people, exercise and physical therapy play important roles in treating JA. Parents can arrange for children to participate in activities that the doctor recommends. During symptom-free periods, many doctors suggest playing team sports or doing other activities to help keep the joints strong and flexible and to provide play time with other children and encourage appropriate social development.

- Work closely with the school to develop a suitable lesson plan for the child and to educate the teacher and the child's classmates about JA. Some children with JA may be absent from school for prolonged periods and need to have the teacher send assignments home. Some minor changes such as an extra set of books or leaving class a few minutes early to get to the next class on time can be a great help. With proper attention, most children progress normally through school.

- Treat the child as normally as possible. Explain to the child that getting JA is nobody's fault. Some children believe that JA is a punishment for something they did. Consider joining a support group. The American Juvenile Arthritis Organization runs support groups for people with JA and their families. Support group meetings provide the chance to talk to other young people and parents of children with JA and may help a child and the family cope with the condition.

Resources

BOOKS

Gray, Susan H., and Serge Bloch. Living with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chanhassen, MN: Child's World, 2002.

The Official Patient's Sourcebook on Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Revised and Updated Directory for the Internet Age. San Diego, CA: Icon Health Publications, 2002.

PERIODICALS

Boschert, Sherry. "Subtle Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis May Be More Common Than Thought." Pediatric News 37 (April 2003): 36.

Brunk, Doug. "When a Limp Signals Something More Serious: Make Sure to Examine the Hips." Family Practice News 34 (May 15, 2004): 50–51.

Labyak, Susan E., et al. "Sleep Quality in Children with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis." Holistic Nursing Practice 17 (July-August 2003): 193–200.

ORGANIZATIONS

American Juvenile Arthritis Organization. 1330 West Peachtree St., Atlanta, GA 30309. Web site: http://www.arthritis.org.

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 1 AMS Circle, Bethesda, MD 20892–3675. Web site: http://www.niams.nih.gov/.

WEB SITES

"Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis." KidsHealth , November 2001. Available online at http://kidshealth.org/parent/medical/arthritis/jra.html (accessed November 10, 2004).

"Types of Juvenile Arthritis." Arthritis Foundation , 2004. Available online at <www.arthritis.org/conditions/DiseaseCenter/typesofJA.asp> (accessed November 10, 2004).

Rosalyn S. Carson-DeWitt Ken R. Wells