Vaccination

Definition

Vaccination introduces a vaccine into the body to produce immunity and prevent specific diseases.

Description

Many diseases that once caused widespread illness, disability, and death are now prevented by vaccines in developed countries. Vaccines are medicines that contain weakened or dead bacteria or viruses. When a child receives a vaccine, his or her immune system responds by producing antibodies, substances that weaken or destroy disease-causing organisms. When the child comes in contact with live bacteria or viruses of the same kind that are in the vaccine, the antibodies prevent those organisms from making the child sick. Vaccines also stimulate the cellular immune system. In other words, the child becomes immune to the disease the organisms normally cause. Building immunity by using a vaccine is called immunization. Childhood immunizations are safe and remain the most effective way to prevent disease.

Vaccines contain antigens (weakened or dead viruses, bacteria, and fungi that cause disease and infection). When introduced into the body, the antigens stimulate the immune system response by instructing B cells to produce antibodies, with assistance from T-cells. The antibodies are produced to fight the weakened or dead viruses in the vaccine. The antibodies "practice" on the weakened viruses, preparing the immune system to destroy real and stronger viruses in the future. When new antigens enter the body, white blood cells (called macrophages) engulf them, process the information contained in the antigens, and send it to the T-cells so that an immune system response can be mobilized.

General use

In the early 2000s, children in the United States and in other developed countries routinely have a series of vaccinations that begins at birth. Vaccinations in children began about 1900 with the smallpox vaccine. In 1960 there were only five vaccines in eight shots. The number of vaccinations children receive has steadily increased since that time. As of 2004, children receive 11 different vaccines given in up to 20 shots by age two years. Given according to a specific schedule, these vaccinations protect against hepatitis B ; diphtheria , tetanus , pertussis ( whooping cough ) (DTP); measles , mumps , rubella (German measles); varicella ( chickenpox ); polio ; pneumococcus; and Haemophilus influenza type B (Hib disease, a major cause of spinal meningitis ) and, in some states, hepatitis A . This series of vaccinations is recommended by the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is a requirement in all states before children can enter school. States make exceptions for children who have medical conditions such as cancer that prevent them from having vaccinations, and some states also make exceptions for children whose parents object for religious or other reasons.

Several vaccines are delivered in one injection, such as the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) combinations.

Vaccines are used in several ways. Some vaccines, such as the rabies vaccine , are given only when a child comes in contact with the virus that causes the disease, such as through a dog bite.

Recommendations for other vaccines and immunobiologic medicines depend on the child's health status or area of world where the family might travel. Such treatments are vaccine or immune globulin for hepatitis A, typhoid, meningitis, Japanese encephalitis , and rabies .

In addition the uses discussed above, vaccines are available for preventing anthrax, cholera, plague, tuberculosis , and yellow fever. Most vaccines are given as injections, but a few are taken orally.

The administration of vaccines to meet travel requirements should not interfere with or postpone any

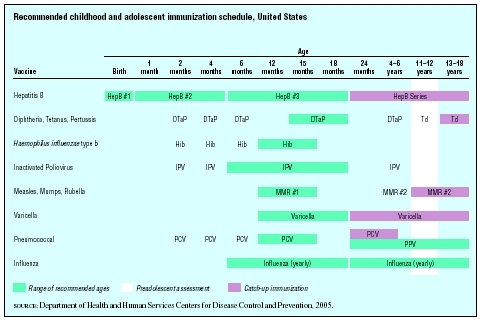

| Age | ||||||||||||

| Vaccine | Birth | 1 month | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | 12 months | 15 months | 18 months | 24 months | 4–6 years | 11–12 years | 13–18 years |

| Range of recommended ages Preadolescent assessment Catch-up immunization | ||||||||||||

| SOURCE : Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005. | ||||||||||||

| Hepatitis B | HepB #1 | HepB #2 | HepB #3 | HepB Series | ||||||||

| Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis | DTaP | DTaP | DTaP | DTaP | DTaP | Td | Td | |||||

| Haemophilus influenzae type b | Hib | Hib | Hib | Hib | ||||||||

| Inactivated Poliovirus | IPV | IPV | IPV | IPV | ||||||||

| Measles, Mumps, Rubella | MMR #1 | MMR #2 | MMR #2 | |||||||||

| Varicella | Varicella | Varicella | ||||||||||

| Pneumococcal | PCV | PCV | PCV | PCV | PCV | |||||||

| PPV | ||||||||||||

| Influenza | Influenza (yearly) | Influenza (yearly) | ||||||||||

of the routine childhood immunizations. If necessary, the routine immunization schedule can be accelerated to give as many vaccines as possible before departure. Decisions about vaccinations for children with chronic illnesses are made with the child's doctor.

Parents who are planning to travel with children to another country should find out what vaccinations are needed. Some vaccinations may be needed 12 weeks before the trip, so getting this information early is important. Many major hospitals and medical centers have travel clinics that provide this information. The traveler's health section of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has information on vaccination requirements.

A vaccination health record helps parents and healthcare providers keep track of a child's vaccinations. The record should start when the child has his or her first vaccination and should be kept up-to-date with each added vaccination. While most doctors follow the recommended vaccination schedule, some flexibility is allowed. For example, vaccinations scheduled for age two months may be given anytime between six to ten weeks. Slight departures from the schedule do not keep the child from developing immunity, as long as all the vaccinations are received close to the right times.

Precautions

Vaccines are not always effective, and there is no way to predict whether a vaccine will "take" in any particular child. To be most effective, vaccination programs depend on the whole community participating. An increase in the number of vaccines given to children and the increased percentage of children receiving vaccines has resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of vaccine-preventable diseases. In the United States, most young parents as of 2004 had never seen many of diseases that vaccines prevent. Even people who do not develop immunity through vaccination are safer because their friends, neighbors, children, and coworkers are immunized.

Factors influencing recommendations for childhood vaccination include age-specific risks of disease and complications, the ability of a given age group to respond to the vaccine, and the potential interference with the immune response to transferred maternal antibody. There are vaccines for the youngest age group at risk for developing the disease and known to develop a satisfactory antibody response to the vaccination.

Like most medical procedures, vaccination has risks as well as great benefits. When children receive a vaccine, parents should be told about both. Questions or concerns should be discussed with a doctor or other healthcare provider. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, located in Atlanta, Georgia, is also a good resource for information.

Vaccines may cause problems for children with certain allergies . Children who are allergic to the antibiotics neomycin or polymyxin B should not take rubella vaccine, measles vaccine, mumps vaccine, or the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. Children who have had a severe allergic reaction to baker's yeast should not take the hepatitis B vaccine . Patients who are allergic to antibiotics such as gentamicin sulfate, streptomycin sulfate, or other amino glycosides should check with their doctors before the taking influenza vaccine, as some influenza vaccines contain small amounts of these drugs. Also, some vaccines, including those for influenza, measles, and mumps, are grown in the laboratory in fluids of chick embryos, and should not be given to children who are allergic to eggs. In general, parents of children who have had an unusual reaction to a vaccine in the past should report the reaction to the doctor before taking the same vaccine again. Doctors need to know about allergies to foods, medicines, preservatives, or other substances.

Children with other medical conditions should be given vaccines with caution. Influenza vaccine may reactivate Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) in patients who have had it before. This vaccine also may worsen illnesses that involve the lungs, such as bronchitis or pneumonia . Vaccines that cause fever as a side effect may trigger seizures in people who have a history of seizures caused by fever.

Certain vaccines are not recommended during pregnancy. However, women who are at risk of getting specific disease such as polio may receive the vaccine to prevent medical problems in their babies. Vaccinating a pregnant woman with tetanus toxoid can prevent tetanus in the baby at birth.

Women should avoid becoming pregnant for three months after taking rubella vaccine, measles vaccine, mumps vaccine, or the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) as these vaccines may cause problems in the unborn baby.

Women who are breastfeeding should check with their doctors before taking any vaccine.

Side effects

Most side effects from vaccines are minor and easily treated. The most common are pain , redness, and swelling at the injection site. Some children may also develop a fever or a rash. Rarely, vaccines may cause severe allergic reactions, swelling of the brain, or seizures. Unusual reaction after receiving a vaccine should be reported to the doctor right away.

Interactions

Vaccines may interact with other medicines and medical treatments. When this happens, the effects of the vaccine or the other medicine may change or the risk of side effects may be greater. Radiation therapy and cancer drugs may reduce the effectiveness of many vaccines or may increase the chance of side effects. Parents should let the doctor know of all medicines taken by the child and learn whether the possible interactions could interfere with the therapeutic effects of the vaccine or the other medicines.

Parental concerns

All vaccines used for routine child vaccinations in the United States may be given simultaneously. There is no evidence that simultaneous administration of vaccines either reduces vaccine effectiveness or increases the risk of adverse events. The only vaccines which should not be given at the same time are cholera and yellow fever vaccines.

Some vaccines are mixed in one solution, such as measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) combination. A survey of the literature as of 2004 indicated no evidence supporting the idea that multiple vaccines in any way overwhelm or weaken the immune system. Most young infants have strong immune systems that are capable of responding to all the recommended vaccines. The protection from bacterial and viral infections provided by vaccines preserves the infant's immune systems to fight off other infections.

Most doctors follow the recommended vaccination schedule, with some flexibility. For example, vaccinations that are scheduled for age two months may be given anytime between six to 10 weeks. Slight departures from the schedule will not stop the child from developing immunity, as long as the child gets all the vaccinations close the right times.

KEY TERMS

Anthrax —A bacterial infection, primarily of livestock, that can be spread to humans. In humans it affects the skin, intestines, or lungs.

Antibody —A special protein made by the body's immune system as a defense against foreign material (bacteria, viruses, etc.) that enters the body. It is uniquely designed to attack and neutralize the specific antigen that triggered the immune response.

Bacteria —Singluar, bacterium; tiny, one-celled forms of life that cause many diseases and infections.

Cholera —An infection of the small intestine caused by a type of bacterium. The disease is spread by drinking water or eating foods that have been contaminated with the feces of infected people. It occurs in parts of Asia, Africa, Latin America, India, and the Middle East. Symptoms include watery diarrhea and exhaustion.

Encephalitis —Inflammation of the brain, usually caused by a virus. The inflammation may interfere with normal brain function and may cause seizures, sleepiness, confusion, personality changes, weakness in one or more parts of the body, and even coma.

Feces —The solid waste, also called stool, that is left after food is digested. Feces form in the intestines and pass out of the body through the anus.

Guillain-Barré syndrome —Progressive and usually reversible paralysis or weakness of multiple muscles usually starting in the lower extremities and often ascending to the muscles involved in respiration. The syndrome is due to inflammation and loss of the myelin covering of the nerve fibers, often associated with an acute infection. Also called acute idiopathic polyneuritis.

Immune system —The system of specialized organs, lymph nodes, and blood cells throughout the body that work together to defend the body against foreign invaders (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.).

Immunization —A process or procedure that protects the body against an infectious disease by stimulating the production of antibodies. A vaccination is a type of immunization.

Inflammation —Pain, redness, swelling, and heat that develop in response to tissue irritation or injury. It usually is caused by the immune system's response to the body's contact with a foreign substance, such as an allergen or pathogen.

Meningitis —An infection or inflammation of the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. It is usually caused by bacteria or a virus.

Microorganism —An organism that is too small to be seen with the naked eye, such as a bacterium, virus, or fungus.

Organism —A single, independent unit of life, such as a bacterium, a plant, or an animal.

Plague —A serious, potentially life-threatening infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis . The disease is usually transmitted to humans by the bites of infected rodent fleas. There are three major types: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic.

Seizure —A sudden attack, spasm, or convulsion.

Tuberculosis —Tuberculosis (TB) is a potentially fatal contagious disease that can affect almost any part of the body, but is mainly an infection of the lungs. It is caused by a bacterial microorganism, the tubercle bacillus or Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Symptoms include fever, weight loss, and coughing up blood.

Typhoid fever —A severe infection caused by a bacterium, Salmonella typhi . People with this disease have a lingering fever and feel depressed and exhausted. Diarrhea and rose-colored spots on the chest and abdomen are other symptoms. The disease is spread through poor sanitation.

Virus —A small infectious agent consisting of a core of genetic material (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a shell of protein. A virus needs a living cell to reproduce.

Yellow fever —An infectious disease caused by a virus. The disease, which is spread by mosquitoes, is most common in Central and South America and Central Africa. Symptoms include high fever, jaundice (yellow eyes and skin) and dark-colored vomit, a sign of internal bleeding. Yellow fever can be fatal.

Immunizations are not given when a child has signs of an acute illness. An interrupted primary series of immunizations need not started again but may simply continue after the child recovers. The child's doctor is the best person to decide when each vaccination should be given.

The eventual goal in child care is to reduce stress. Parents should try to increase the child's feeling of security and well-being by close involvement with the immunization process. Providing explanations of the immunization plan, special tests, and procedures suitable to the child's age is helpful. Infants and toddlers are not likely to understand verbal explanations, but they have a strong parental attachment and need affection to ease fears. Small children also have an urgent need for their mothers to defend them during medical treatments. Older children may even protest or despair in getting an injection but are usually accepting of reasonable explanations.

The health-care professional reviews the immunization record and the health status of the child at each visit. If necessary the nurse or doctor helps the parent correctly position the child and exposure of the injection site. Parents should hold a small child on their laps securely for the injection; older children may be put on the examination table in the doctor's office. After the injection, parents can give the child immediate comfort to control crying and then leave the treatment room.

Resources

BOOKS

Institute of Medicine Staff, et al. Immunization Safety Review: Multiple Immunizations and Immune Dysfunction. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2002.

Kassianos, George C., et al. Immunization: Childhood and Travel Health. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Inc., 2001.

Parents Guide to Childhood Immunization. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2001.

Studor, Hans-Peter, et al. Vaccination: A Guide for Making Personal Choices. Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris Books, 2004.

WEB SITES

Centers for Disease Control National Immunization Program. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/nip (accessed December 3, 2004).

"Vaccination Recommendations for Infants and Children." CDC Travelers' Health: Health Information for International Travel, 2003–2004. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/travel/child-vax.htm (accessed December 3, 2004).

Aliene S. Linwood, RN, DPA, FACHE

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: