Food allergies and sensitivities

Definition

A food allergy or sensitivity is a person's immune system reaction to eating a particular food.

Description

The word allergy comes from two Greek words: alos, meaning "other" and argon, meaning "action." When one has an allergy, he or she has a reaction other than the one expected.

Food allergies and sensitivities are the body's reaction to a specific food. In a food allergy or sensitivity, when the child eats a particular food, (such as eggs, for example) usually by the time the eggs reach the stomach or the intestines, the body reads the presence of eggs as an allergen (something harmful). It sends out immunoglobulin E (IgE), an antibody, to destroy the eggs and protect the body, releasing histamines. The body remembers and produces histamines every time the food is eaten. These histamines trigger allergic symptoms that affect many areas of the body, particularly the skin, respiratory system, nervous system, and digestive system. Digestive disorders after eating specific foods are not always allergies. These reactions can be food sensitivities or intolerances. They can also be symptoms of other, more serious digestive diseases and malfunctions.

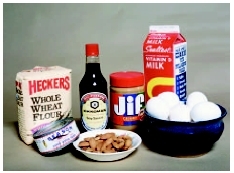

In the United states, 90 percent of all food allergies are caused by wheat, peanuts, nuts, milk, eggs, shellfish, soy, and fish. Many other foods can be at the root of food allergies or sensitivities, especially berries and other fruits, tomatoes, corn, and some meats like pork. Migraine headaches have been associated with sensitivities to chemicals contained in red wine, deli meats, aged cheeses, and the tannins in tea.

Usually, when a child is allergic to one food in a food family, he or she will most likely react to other foods in that food family. For example, if a child is sensitive to one type of fish, he or she also may be sensitive to other types of fish. This is called cross-reactivity.

Demographics

Nearly three million children in the United States have been diagnosed with food allergies. Nearly 600,000 of them have severe allergies to peanuts and possibly twice as many have severe shellfish allergies. Each year about 200 adults and children in the United States die from food-related anaphylaxis , an extreme reaction that causes swelling of the throat and bronchial passages, shock, and a severe drop in blood pressure. Nevertheless, food allergies tend to be under-diagnosed by doctors.

Genetics seems to play a part in food allergies. If one parent has a food allergy, the child's risk of having a food allergy is doubled. If both parents have food allergies, the risk is even higher. The child, however, may be allergic to a completely different food from the one to which the parent has demonstrated sensitivity. There also is increased risk when there are other kinds of allergy-related diseases in the family, such as hay fever or asthma .

Causes and symptoms

Causes

Allergies are caused by the immune system's reaction to a particular food. Usually, a child will have had a prior exposure before IgE or specific histamines are produced.

Food intolerance is often put into the same category as food allergy, even though there may be an entirely different mechanism involved. In these cases, the digestive tract reacts to a specific part of the food; for example, the protein or the sugar in a specific food. The digestive system rebels, resulting in gas, bloating, upset stomach, diarrhea , nausea , or vomiting . Many times, these responses are due to eating food contaminated with bacteria, rather than a true food allergy. In other cases, the child's reaction is due to an underlying digestive disorder such as irritable bowel syndrome , which is a chronic condition that is often triggered by specific types of food.

Gluten intolerance is not an allergy. It is a disease called celiac disease , or gluten-sensitive enteropathy. The body cannot process gluten found in wheat and other grains. Though the immune system is involved, celiac disease does not behave as a true allergy. Its treatment is like many food allergies, namely avoidance of the offending substance, which in this case is gluten.

Some children may lack a specific enzyme needed to metabolize certain foods. About 10 percent of all adults and older children have lactose intolerance . There are two forms of lactose intolerance: inherited and acquired. The inherited form (autosomal recessive) is extremely rare and severe. The acquired type is very common, and occurs in older children (not infants) and adults. It is distressing, but not life-threatening, and occurs with increased frequency in African Americans. Sometimes infants, as well as older children and adults, have a transient lactose deficiency after an episode of diarrhea.

Children with lactose intolerance have a lactase deficiency that keeps them from processing milk and milk products. These children can often drink milk that has had this enzyme introduced into the product. Some children can drink milk that has acidophilus bacteria put into it. This bacteria breaks down the lactose, or milk sugar, in the milk so that the child can tolerate it. Some children with lactose intolerance cannot drink whole milk, but can eat cheese or drink low-fat buttermilk in small quantities. This is different from a true milk allergy where even a small amount of any dairy product will produce a reaction.

Some children may also be intolerant of food colorings, additives, and preservatives. Among these are yellow dye number 5, which can cause hives ; and monosodium glutamate, which produces flushing, headaches, and chest pain . Sulfites, another additive, have been found to cause asthmatic reactions and even anaphylactoid reactions. Sulfites are preservatives used in wines, maraschino cherries, seafood, and soft drinks. They are sometimes put on fresh fruits and lettuce to maintain their fresh appearance, on red meats to prevent brown discoloration, and even in prepared deli foods like crab salad. Sulfites appear on food labels as sodium sulfite, sodium bisulfite, potassium bisulfite, sulfur dioxide, and potassium metabisulfite. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has banned the use of sulfites as a preservative for fruits and vegetables, but they are still in use in some foods.

Symptoms

Food allergies and sensitivities can produce a wide range of symptoms involving the skin, respiratory system, and nervous system. Children may have watery eyes, runny noses, and sneezing.

Skin rashes or hives can range from measles-like rashes to itchy welts. The rashes or welts can appear on a specific part of the body or can be widespread. Some children have swelling of the eyes, lips, and/or tongue.

Symptoms vary among children, even those who are sensitive to the same food. One child's specific reaction to an offending food does not mean that all children react the same. Nut allergies and shellfish, however, seem to be the most documented triggers for anaphylaxis. Nevertheless, anaphylaxis is not limited to those foods. IgE-mediated allergic reactions can progress to other allergic symptoms. For example, a child who has had hives is at risk for angioedema (swelling of the blood vessels) and anaphylaxis.

Symptoms also vary in intensity and by the amount eaten. One child may have a mild rash on the forearms when eating half a dozen strawberries. Another may be covered with a rash after eating only one. This variation is individualized and is a factor in the body's sensitivity to the target food.

Although the time between ingestion and symptoms is somewhat variable for allergic reactions (IgE-mediated), the vast majority occur within minutes. Nearly all occur within two hours. Reactions due to intolerances, like lactose, may occur somewhat later. Symptoms occurring days after a food is ingested are not likely related to the food.

When to call the doctor

Anaphylaxis is an extreme reaction to a food, usually peanuts or nuts. It causes swelling of the throat and bronchial passages, a drop in blood pressure, shock, and even death. A child with anaphylaxis should be taken to the emergency room immediately. If an emergency epinephrine pen is available, it should be administered immediately.

If a child experiences any type of allergy symptoms after eating, the child should be evaluated. Of particular concern are digestive symptoms that keep the child from eating properly or cause the child to lose weight. Equally important are neurological symptoms, especially headaches. Digestive and neurological symptoms could also be an indication of other underlying disorders. Therefore, the child should be seen by a doctor.

Diagnosis

Having a child evaluated as soon as possible will identify the offending food and allow parents to eliminate it from the child's diet. Many allergists, or doctors who specialize in allergies, will do a skin-prick test followed by a blood test. The skin-prick test is a series of pricks on the child's skin with a plastic applicator that contains a single food in concentrated form. A food allergy has been identified if the child's skin reacts by welting or becoming red. The skin-prick test for foods (not for aeroallergens) has a high incidence of false positives; that is, the test may be positive but the child is not truly allergic, or does not have symptoms from the food. This test is not used on a child with severe anaphylactic reactions or on children with widespread eczema, a skin disorder.

The allergist may also do a food challenge in the doctor's office. The child is fed the suspected food in increasing amounts to see what kind of reaction occurs.

One of the tests allergists use is called the RAST (Radio-Allergo-Sorbent Test). It measures the amount of IgE antibody in the blood that is produced for certain known food allergens. Like the skin-prick test, RAST and other antibody tests have a high rate of false positives.

Some doctors will put the child on an elimination diet for one week to 10 days. The basic elimination diet is a series of foods that have proven not to be allergy triggers. This diet consists of foods such as lamb, poultry, rice, vegetables, and all fruits, except citrus and berries. One new food is introduced each week. Parents record the child's reaction to each food. If the child has no reaction, the food is considered safe and can remain in the diet. If there is a reaction, it is noted and the food is removed. The child continues the elimination diet for a few more days, at which time another food is introduced. The elimination diet is often done after skin testing, so there is a logical guide for what to eliminate.

Treatment

The only treatment for IgE-mediated reactions to foods is avoidance. These reactions, as well as intolerances, are not responsive to desensitization. An epi-pen should be kept in the home for all IgE mediated food allergies and all inadvertent reactions should be treated.

It is not unusual for children to crave the very foods to which they are allergic. When the child is placed on an elimination diet, often the body will rebel at not being given the foods that cause it to react and will produce cravings for those foods.

Some doctors will prescribe antihistamines to help manage symptoms. These, however, are for use after an episode and not for an extended period.

Nutritional concerns

Eliminating one food or even one food family from a child's diet will not interfere with his or her nutritional needs, nor will it keep the child from growing properly. There is enough variety in the foods available in the American diet to meet any child's needs. Some foods, however, may be difficult to find sufficient replacements for if the child wants substitutes. Wheat is particularly difficult to replace, although bread, pasta, and pastry products made with oat and rice flours are good substitutes. However, they do not taste or look exactly like risen wheat bread or regular pasta.

Prognosis

Children are known to outgrow milk allergies in most cases, but—for safety purposes—reintroduction in a medical setting is advised. Egg allergy disappearance is not as high as it is for milk allergy. Sensitivities to wheat and soy are also outgrown. Allergies to peanuts, shellfish, and other foods that can produce anaphylaxis usually remain with the child throughout life.

Prevention

If both parents have food allergies, precautions should be taken to minimize the risk of the child having a food allergy, too. Before birth and while breastfeeding, the mother can limit the baby's exposure to allergens by not bingeing on foods known to cause allergies. Breast-feeding delays the onset of allergies, but does not avoid them. The secretory IgA in breast milk fights infection but is not shown to avoid absorption of allergies.

Solid foods are slowly introduced at four to six months of age. The first solid foods should be those that have shown the potential for not producing an allergic reaction, such as fruits (except citrus fruits and berries), vegetables, and rice. Early introduction of highly allergenic foods may predispose a child to reactions, but this is controversial. It is recommended that parents avoid feeding the child highly allergenic foods until three years of age, if possible. The list of highly allergenic foods includes nuts, peanuts, fish, shellfish, and eggs. Whole cow's milk—not cow's milk formula—should be avoided during the first year. Having the child eat a variety of foods will also keep the child from too much exposure to any one particular food family.

KEY TERMS

Allergen —A foreign substance that provokes an immune reaction or allergic response in some sensitive people but not in most others.

Allergists —Doctors who specialize in allergies.

Antibody —A special protein made by the body's immune system as a defense against foreign material (bacteria, viruses, etc.) that enters the body. It is uniquely designed to attack and neutralize the specific antigen that triggered the immune response.

Cross-reaction —A reaction that occurs in blood testing when a disease agent reacts to the specific antibody for another disease agent.

Histamine —A substance released by immune system cells in response to the presence of an allergen. It stimulates widening of blood vessels and increased porousness of blood vessel walls so that fluid and protein leak out from the blood into the surrounding tissue, causing localised inflammation of the tissue.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) —Immunoglobulin type gamma, the most common type found in the blood and tissue fluids.

Lactose —A sugar found in milk and milk products.

Parents should make sure that the baby's first foods and those during the first few years of life are pure, unprocessed foods. Packaged and prepared foods (soups, stews, and toddler dinners, for example) contain many foods mixed together, along with fillers, usually wheat products, and possibly flavorings, sugar, and salt. By feeding a toddler a piece of boneless chicken, some green peas, a few cooked carrots, and a bit of potato instead of a can of chicken stew, parents can identify exactly what foods the child is eating and in what quantities. Therefore, if there is an allergic reaction, it is easier to identify what triggered it.

Parental concerns

Because children can come into contact with food allergens at school and during extracurricular activities , parents should meet with school officials to discuss procedures for keeping their children safe. Parents and school personnel should develop an action plan for dealing with allergens in the school and handling an emergency. Not only should the cafeteria staff be notified about the food allergy, but parents should also ask about snack time, birthdays and holiday celebrations, field trips, and arts and crafts projects. Arrangements should be made to keep medications to treat accidental exposure at the school, and personnel should be trained in their use.

Due to the seriousness of nut allergies and other allergies that can cause anaphylaxis, some school districts have created policies that forbid nuts on school premises and do not allow students to trade food at lunch. Some parents have lobbied school boards for such restrictions.

Avoiding the trigger food may be very problematic, even at home. Parents need to become proficient label readers, especially if the allergen is a nut or other food that may cause anaphylaxis. Understanding what the ingredient names mean is critical to total food avoidance. For example, dairy products can be listed as milk, casein, whey, and sodium caseinate. If a child is allergic to corn, it can be found not only as corn and corn syrup, but also cornstarch, which is a binding agent in a number of medications, including acetaminophen (Tylenol). Consultation with a dietitian can help parents understand food labels.

Peanut allergies in the United States doubled between 1997 and 2002. A controversial British study, reported in 2003, found a peanut/soy link, which is clinically rare. The study reported a link between early use of soy formula and peanut oil baby lotion in the later diagnosis of peanut food allergy. Soy formula may sensitize an infant to legumes, and therefore to peanuts. Peanut oil, known by doctors and nurses as arachis oil, is found in baby lotion and creams, especially those used to treat diaper rash , eczema, and dry skin.

Children who have severe reactions to a trigger food should wear a medical alert bracelet. Parents should also have on hand an emergency epinephrine-filled syringe like those found in bee-sting kits, or an epinephrine pen.

Parents should also notify day-care providers, Girl Scout and Boy Scout leaders, religious education teachers, sports coaches, and parents of their child's friends. They should explain what foods their child is allergic to, how the child reacts to the food, and how adults can help, either by making sure these foods are not served as snacks or by giving emergency care or support during an allergic reaction. In addition, parents can teach their child how to ask for help.

See also Lactose intolerance .

Resources

BOOKS

Barber, Marianne S. The Parent's Guide to Food Allergies: Clear and Complete Advice from the Experts on Raising Your Food-Allergic Child. NY: Owl Books, 2001.

Coss, Linda Marienhoff. What's to Eat? The Milk-Free, Egg-Free, Nut-Free Food Allergy Cookbook. Lake Forest, CA: Plumtree Press, 2000.

Smith, Nicole S. Allie the Allergic Elephant: A Children's Story of Peanut Allergies. San Francisco: Jungle Communications, Inc., 2002.

Weiner, Ellen, and Moss Freedman. Taking Food Allergies to School. Plainville, NY: JayJo Books, 1999.

Young, Michael C. The Peanut Allergy Answer Book. Gloucester, MA: Fair Winds Press, 2001.

PERIODICALS

". . .And It's Easy to Misinterpret Correct Food Labels." Child Health Alert (Oct. 2002): 42–4.

"Origins of Peanut Allergy." Archives of Disease in Childhood. 88, no. 8 (August 2003): 694.

Vander Shaaf, Rachelle. "Is It a Food Allergy?" Parenting XVI, no. 5 (June 1, 2002): 38.

ORGANIZATIONS

Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network. 11781 Lee Jackson Hwy., Suite 160, Fairfax, VA 22033-3309. (800) 929-4040. Web site: http:///www.foodallergy.org.

Janie Franz

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: