Tay-Sachs disease

Definition

Tay-Sachs disease is a genetic disorder caused by a missing enzyme that results in the accumulation of a fatty substance in the nervous system. This disease causes disability and death.

Description

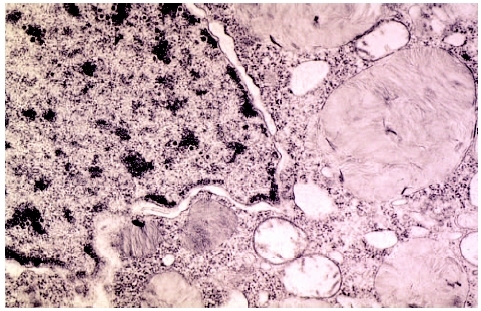

Gangliosides are fatty substances necessary for the proper development of the brain and nerve cells (nervous system). Under normal conditions, gangliosides are continuously broken down, so that an appropriate balance is maintained. In Tay-Sachs disease, the enzyme necessary

Demographics

Tay-Sachs disease is particularly common among Jewish people of Eastern European and Russian (Ashkenazi) origin. About one out of every 2,500 to 3,600 babies born to Ashkenazi Jewish couples have the disease. In the general population about one out of every 320,000 babies born has Tay-Sachs disease. Approximately one in 30 Ashkenazi Jews is a carrier of the gene that causes the disease. Tay-Sachs is also more common among certain French-Canadian, Pennsylvania Dutch, and Cajun families.

Causes and symptoms

Tay-Sachs is caused by a defective gene. Genes are located on chromosomes and serve to direct specific developments and processes within the body. The genetic defect in Tay-Sachs disease results in the lack of an enzyme called hexosaminidase A. Without this enzyme, gangliosides cannot be broken down. They build up within the brain, interfering with nerve functioning. Because Tay-Sachs is a recessive disorder, only people who receive two defective genes (one from the mother and one from the father) will actually have the disease. People who have only one defective gene and one normal gene are called carriers. They carry the defective gene and thus the possibility of passing the gene and/or the disease onto their offspring.

When a carrier and a non-carrier have children, none of their children will actually have Tay-Sachs. The statistical probability is that 50 percent of their children will be carriers themselves. When two carriers have children, their children have a 25 percent chance of having normal genes, a 50 percent chance of being carriers of the defective gene, and a 25 percent chance of having two defective genes. Only the individual with two defective genes actually has the disease.

Classic Tay-Sachs disease strikes infants around the age of six months. Up until this age, the baby appears to develop normally. When Tay-Sachs begins to show itself, the baby stops interacting with other people and develops a staring gaze. Normal levels of noise startle the baby to an abnormal degree. By about one year of age, the baby has very weak, floppy muscles and may be completely blind. The head is quite large. Children with Tay-Sachs also have other symptoms, such as loss of peripheral (side) vision, inability to breathe and swallow, and paralysis as the disorder progresses. Seizures become a problem between ages one and two, and the baby usually dies by about age four.

A few variations from this classical progression of Tay-Sachs disease are possible:

- Juvenile hexosaminidase A deficiency: Symptoms appear between ages two and five; the disease progresses more slowly, with death by about 15 years.

- Chronic hexosaminidase A deficiency: Symptoms may begin around age five or may not occur until between 20 and 30 years of age. The disease is milder. Speech becomes slurred. The individual may have difficulty walking due to weakness, muscle cramps , and decreased coordination of movements. Some individuals develop mental illness. Many have changes in intellect, hearing, or vision.

When to call the doctor

If the child has any noticeable problems that might be associated with Tay-Sachs disease or appears to stop developing normally after a period of normal development, the doctor should be consulted.

Diagnosis

Examination of the eyes of a child with Tay-Sachs disease reveals a characteristic cherry-red spot at the back of the eye in an area called the retina. Tests to determine the presence and quantity of hexosaminidase A can be performed on the blood, specially treated skin cells, or white blood cells. A carrier has about half the normal level of hexosaminidase A present, while an individual with the disease has no hexosaminidase A at all.

Treatment

Providing good, supportive care and treating the symptoms as they arise is the only way to treat Tay-Sachs; there is no way to treat the disease itself.

Prognosis

The prognosis for a child with classic Tay-Sachs disease is death. Because the chronic form of Tay-Sachs was discovered near the end of the 2000s, prognosis for this type of the disease was, as of 2004, not completely known.

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent Tay-Sachs disease. It is, however, possible to identify carriers of the disease and provide them with genetic counseling and appropriate information concerning the chance of their offspring having Tay-Sachs disease. When the levels of hexosaminidase A are half the normal level, a person is a carrier of the defective gene. Blood tests of carriers reveal reduction of hexosaminidase A.

When a woman is already pregnant, tests can be performed on either the cells of the fetus ( amniocentesis ) or the placenta (chorionic villus sampling) to determine whether the baby will have Tay-Sachs disease.

Parental concerns

If parents are thinking of having a child and believe they might be carriers of Tay-Sachs, they should be screened so that they can assess their options. Children born with infantile Tay-Sachs, even with the best available care, usually die before the age of five. Children born with juvenile Tay-Sachs usually die before the age of 15.

KEY TERMS

Ganglioside —A fatty (lipid) substance found within the brain and nerve cells.

Resources

BOOKS

Behrman, Richard E., Robert M. Kliegman, and Hal B. Jenson. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics , 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004.

Desnick, Robert, and Michael M. Kaback, eds. Tay-Sachs Disease. San Diego, CA: Academic, 2001.

ORGANIZATIONS

March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation. 1275 Mamaroneck Avenue, White Plains, NY 10605. Web site: http://www.modimes.org.

National Tay-Sachs and Allied Diseases Association. 2001 Beacon Street, Suite 204, Brighton, MA 02135. Web site: http://www.ntsad.org.

Tish Davidson, A.M.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: