Schizophrenia

Definition

Schizophrenia is a mental illness characterized by disordered thinking, delusions, hallucinations, emotional disturbance, and withdrawal from reality.

Description

Some experts view schizophrenia as a group of related illnesses with similar characteristics. Although the term, coined in 1911 by Swiss psychologist Eugene Bleuler (1857–1939), is associated with the idea of a "split" mind, the disorder is different from a "split personality" (dissociative identity disorder), with which it is frequently confused. In the United States, schizophrenics occupy more hospital beds than patients suffering from cancer , heart disease, or diabetes. At any given time, they account for up to half the beds in long-term care facilities and 40 percent of the treatment days.

Demographics

The incidence of childhood schizophrenia is thought to be one in 10,000 births. In comparison, the incidence among adolescents and adults is approximately one in 100. The condition occurs with equal frequency in males and females (although the onset of symptoms is usually earlier in males). At least 2.5 million Americans are thought to be afflicted with schizophrenia, with an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 new cases every year. Schizophrenia is commonly thought to disproportionately affect people in the lowest socioeconomic groups, although some people claim that socially disadvantaged persons with schizophrenia are only more visible than their more privileged counterparts, not more numerous.

Causes and symptoms

While the exact cause of schizophrenia is not known, it is believed to be caused by a combination of physiological and environmental factors. Studies have shown that there is clearly a hereditary component to the disorder. Family members of schizophrenics are ten times more prone to schizophrenia than the general population, and identical twins of schizophrenics have a 46 percent likelihood of having the illness themselves. Relatives of schizophrenics also have a higher incidence of other milder psychological disorders with some of the same symptoms as schizophrenia, such as suspicion, communication problems, and eccentric behavior.

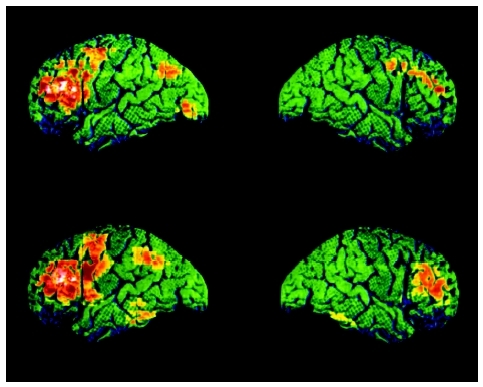

In the years following World War II (1939–45), many doctors blamed schizophrenia on bad parenting. In the latter twentieth century, however, advanced neurological research strengthened the case for a physiological basis for the disease. It has been discovered that the brains of schizophrenics have certain features in common, including smaller volume, reduced blood flow to certain areas, and enlargement of the ventricles (cavities filled with fluid that are found at the brain's center). Much attention has focused on the connection between schizophrenia and neurotransmitters, the chemicals that transmit nerve impulses within the brain. One such chemical, dopamine, has been found to play an especially important role in the disease. Additional research has concentrated on how and when the brain abnormalities that characterize the disorder develop. Some are believed to originate prenatally for a variety of reasons, such as trauma, viral infections, malnutrition during pregnancy, or Rh sensitivity (a reaction caused when the mother lacks a certain blood protein called Rh that the baby has). Environmental factors associated with schizophrenia include birth complications, viral infections during infancy, and head injuries in childhood. While the notion of child-rearing practices causing schizophrenia has been largely discredited, there is evidence that certain family dynamics do contribute to the likelihood of relapse in persons who already have shown symptoms of the disease.

Researchers have found correlations between childhood behavior and the onset of schizophrenia in adulthood. A 30-year longitudinal research project studied over 4,000 people born within a single week in 1946 in order to document any unusual developmental patterns observed in those children who later became schizophrenic. It was found that a disproportionate number of them learned to sit, stand, and walk late. They were also twice as likely as their peers to have speech disorders at the age of six and to have played alone when they were young. Home movies have enabled other researchers to collect information about the childhood characteristics of adult schizophrenics. One study found that the routine physical movements of these children tended to be slightly abnormal in ways that most parents would not suspect were associated with a major mental illness and that the children also tended to show fear and anger to an unusual degree.

The initial symptoms of schizophrenia usually occur between the ages of 16 and 30, with some variation depending on the type. Disorganized schizophrenia tends to begin early, usually in adolescence or young adulthood, while paranoid schizophrenia tends to start later, usually after the age of 25 or 30. The onset of schizophrenia before the age of 13 is rare and is associated with more serious symptoms. The onset of acute symptoms is referred to as the first psychotic break or break from reality. In general, the earlier the onset of symptoms, the more severe the illness is. Before the disease becomes full-blown, schizophrenics may go through a period called the prodromal stage, lasting about a year, when they experience behavioral changes that precede and are less dramatic than those of the acute stage. These may include social withdrawal, trouble concentrating or sleeping, neglect of personal grooming and hygiene, and eccentric behavior.

The prodromal stage is followed by the acute phase of the disease, which usually requires medical intervention. During this stage, three-fourths of schizophrenics experience delusions, illogical and bizarre beliefs that are held despite objections. An example of a delusion is the belief that the afflicted person is under the control of a sinister force located in the sewer system that dictates his every move and thought. Hallucinations are another common symptom of acute schizophrenia. These may be auditory (hearing voices) or tactile (feeling as though worms are crawling over one's skin). The acute phase of schizophrenia is also characterized by incoherent thinking, rambling or discontinuous speech, use of nonsense words, and odd physical behavior, including grimacing, pacing, and unusual postures. Persons in the grip of acute schizophrenia may also become violent, although often this violence is directed at themselves: it is estimated that 15 to 20 percent of schizophrenics commit suicide out of despair over their condition or because the voices they hear "tell" them to do so, and up to 35 percent attempt to take their own lives or seriously consider doing so. In addition, about 25 to 50 percent of people with schizophrenia abuse drugs or alcohol. As the positive symptoms of the acute phase subside, they may give way to what is called residual schizophrenia. Symptoms include flat or inappropriate emotions, an inability to experience pleasure (anhedonia), lack of motivation, reduced attention span, lack of interest in one's surroundings, and social withdrawal.

When to call the doctor

Parents should contact a healthcare professional if their child begins to have auditory or visual hallucinations, has a sudden change in behavior, shows signs of suicide ideation, or exhibits other symptoms of schizophrenia.

Diagnosis

Schizophrenia is generally divided into four types. The most prevalent, found in some 40 percent of affected persons, is paranoid schizophrenia, characterized by delusions and hallucinations centering on persecution, and by feelings of jealousy and grandiosity. Other possible symptoms include argumentativeness, anger, and violence. Catatonic schizophrenia is known primarily for its catatonic state, in which persons retain fixed and sometimes bizarre positions for extended periods of time without moving or speaking. Catatonic schizophrenics may also experience periods of restless movement. In disorganized (hebephrenic) schizophrenia, the patient is incoherent, with flat or inappropriate emotions, disorganized behavior, and bizarre, stereotyped movements and grimaces. Catatonic and disorganized schizophrenia affect far fewer people than paranoid schizophrenia. Most schizophrenics not diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenics fall into the large category of undifferentiated schizophrenia (the fourth type), which consists of variations of the disorder that do not correspond to the criteria of the other three types. Generally, symptoms of any type of schizophrenia must be present for six months before a diagnosis can be made.

Childhood schizophrenia has been known to appear as early as five years of age. Occurring primarily in males, it is characterized by the same symptoms as adult schizophrenia. Diagnosis of schizophrenia in children can be difficult because delusions and hallucinations may be mistaken for childhood fantasies. Other signs of schizophrenia in children include moodiness, problems relating to others, attention difficulties, and difficulty dealing with change. In many cases, children are improperly diagnosed with the disease; one study found as many as 95 percent of children initially diagnosed with childhood-onset schizophrenia did not meet the diagnostic criteria.

It is important for schizophrenia to be diagnosed as early as possible. The longer the symptoms last, the less well afflicted individuals respond to treatment.

Treatment

Even when treated, schizophrenia interferes with normal development in children and adolescents and makes new learning difficult.

Schizophrenia has historically been very difficult to treat, usually requiring hospitalization during its acute stage. In the late 1900s, antipsychotic drugs became the most important component of treatment. These can control delusions and hallucinations, improve thought coherence, and, if taken on a long-term maintenance basis, prevent relapses. However, antipsychotic drugs do not work for all schizophrenics, and their use has been complicated by side effects, such as akathisia (motor restlessness), dystonia (rigidity of the neck muscles), and tardive dyskinesia (uncontrollable repeated movements of the tongue and the muscles of the face and neck). In addition, many schizophrenics resist taking medication, some because of the side effects, others because they may feel better and mistakenly decide they do not need the drugs anymore, or because being dependent on medication in order to function makes them feel bad about themselves. The tendency of schizophrenics to discontinue medication is very harmful. Each time a schizophrenic goes off medication, the symptoms of the disease return with greater severity, and the effectiveness of the drugs is reduced.

Low doses of antipsychotic medication have been used successfully with children and adolescents, especially when administered shortly after the onset of symptoms. Their rate of effectiveness in children between the ages of five and 12 has been found to be as high as 80 percent. Until about 1990, the drugs most often prescribed for schizophrenia were neuroleptics such as Haldol, Prolixin, Thorazine, and Mellaril. A major breakthrough in the treatment of schizophrenia occurred in 1990 with the introduction of the drug clozapine to the U.S. market. Clozapine, which affects the neurotransmitters in the brain (specifically serotonin and dopamine), has been dramatically successful in relieving symptoms of schizophrenia, especially in patients in whom other medications have not been effective. However, even clozapine does not work for all patients. In addition, about 1 percent of those who take it develop agranulocytosis, a potentially fatal blood disease, within the first year of use, and all patients on clozapine must be monitored regularly for this side effect. (Clozapine was first developed in the mid twentieth century but could not be introduced until it became possible to screen for this disorder.) The screening itself is expensive, creating another problem for those using the drug. Risperidone, a subsequent and safer medication that offers benefits similar to those of clozapine, was introduced in 1994 and is as of the early 2000s the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic medication in the United States. Olanzapine, another in the subsequent generation of schizophrenia drugs, received FDA approval in the fall of 1996, and more medications are under development. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT, also called electric shock treatments) has been utilized to relieve symptoms of catatonia and depression in schizophrenics, especially in cases where medication is not effective.

Although medication is an important part of treatment, psychotherapy can also play an important role in helping schizophrenics manage anxiety and deal with interpersonal relationships, and treatment for the disorder usually consists of a combination of medication, therapy, and various types of rehabilitation. Family therapy has worked well for many patients, educating both patients and their families about the nature of schizophrenia and helping them in their cooperative effort to cope with the disorder.

Alternative treatment

Some of the alternative treatments that have been used with varying success to treat children with schizophrenia include biofeedback, acupressure, chiropractic work, massage, and herbal drops.

Nutritional concerns

Some families have reported a benefit to making adjustments to or supplementing the diet of a child with schizophrenia, including reducing the amount of processed sugar consumed and supplementing with vitamins and minerals such as copper, zinc, folic acid , etc.

Prognosis

With the aid of antipsychotic medication to control delusions and hallucinations, about 70 percent of schizophrenics

Prevention

There is no proven way to prevent onset of schizophrenia. Researchers have investigated the possibility of treating schizophrenia during the prodromal stage or even before symptoms start (such as when the likelihood of hereditary transmission is high). Other areas of research include the links between schizophrenia and family stress, drug use, and exposure to certain infectious agents.

Parental concerns

Parents play a key role in the everyday treatment and management of schizophrenia. The affected child should be closely monitored to ensure he or she is taking all prescribed medications. Working with the child's school teachers to formulate a day-to-day schedule can help maintain consistency for the child and address specific developmental delays. Parents should be educated on the signs of relapse and of adverse reactions to the medication, and encourage children in remission to self-report any possible signs of relapse.

Resources

BOOKS

Dalton, Richard, Marc A. Forman, and Neil W. Boris. "Childhood Schizophrenia." In Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics , 17th ed. Edited by Richard E Behrman, Robert M. Kliegman, and Hal B. Jenson. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004.

Moore, David P., and James W. Jefferson, eds. "Schizophrenia." In Handbook of Medical Psychiatry , 2nd ed. New York: Mosby, 2004.

PERIODICALS

Jarbin, Hakan, et al. "Adult Outcome of Social Function in Adolescent-Onset Schizophrenia and Affective Psychosis." Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42, no.2 (February 2003): 176–83.

McClellan, Jon, et al. "Symptom Factors in early-Onset Psychotic Disorders." Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41, no. 7 (July 2002): 791–8.

Schaeffer, John L., and Randal G. Ross. "Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia: Premorbid and Prodromal Diagnostic and Treatment Histories." Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41, no. 5 (May 2002): 538–45.

ORGANIZATIONS

National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. 60 Cutter Mill Rd., Suite 404, Great Neck, NY 11021. Web site: http://www.narsad.org.

National Schizophrenia Foundation. 403 Seymour Ave., Suite 202, Lansing, MI 48933. Web site: http://www.nsfoundation.org.

WEB SITES

Dunn, David W. "Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses." eMedicine , June 17, 2004. Available online at http://www.emedicine.com/ped/topic2057.htm (accessed January 17, 2005).

Stephanie Dionne Sherk

KEY TERMS

Neurotransmitters —Chemicals in the brain that transmit nerve impulses.

Ventricles —Four cavities within the brain that produce and maintain the cerebrospinal fluid that cushions and protects the brain and spinal cord.