Depressive disorders

Definition

Depression and depressive disorders (unipolar depression) are mental illnesses characterized by a profound and persistent feeling of sadness or despair and/or a loss of interest in things that once were pleasurable. Disturbance in sleep , appetite, and mental processes are common symptoms of depression.

Description

Everyone experiences feelings of unhappiness and sadness occasionally. However, when these depressed feelings start to dominate everyday life and cause physical and mental deterioration, they become what are known as depressive disorders.

There are two main categories of depressive disorders: major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. Major depressive disorder is a moderate to severe episode of depression lasting two or more weeks. Individuals experiencing this major depressive episode may have trouble sleeping, lose interest in activities they once took pleasure in, experience a change in weight, have difficulty concentrating, feel worthless and hopeless, or have a preoccupation with death or suicide . In children, the major depression may often appear as irritability.

While major depressive episodes may be acute (intense but short-lived), dysthymic disorder is an ongoing, chronic depression that lasts two or more years (one or more years in children) and has an average duration of 16 years. The mild to moderate depression of dysthymic disorder may rise and fall in intensity, and those afflicted with the disorder may experience some periods of normal, non-depressed mood of up to two months in length. Its onset is gradual, and dysthymic patients may not be able to pinpoint exactly when they started feeling depressed. Individuals with dysthymic disorder may experience a change in sleeping and eating patterns, low self-esteem , fatigue, trouble concentrating, and feelings of hopelessness. Parents of children suffering from dysthymic disorder may notice their child experience a fall in grades and a lack of interest in extracurricular activities that were once enjoyable.

Depression also can occur in bipolar disorder , an affective mental illness that causes radical emotional changes and mood swings, from manic highs to depressive lows. The majority of bipolar individuals experience alternating episodes of mania and depression.

Demographics

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) estimates that one out of every 33 children may suffer from depression. Among adults 18 and older, depressive disorders affect an estimated 18.8 million Americans each year. Women are twice as likely to suffer from a depressive disorder than men; approximately 12.4 million American women and 6.4 million men deal with depression. The average age a first depressive episode occurs is in the mid-20s, although the disorder strikes all age groups indiscriminately, from children to the elderly.

According to the U.S. Surgeon General, major depression occurs in about 5 percent of children between age nine and 17, and at any one point in time, 10 to 15 percent of U.S. children and adolescents experience some symptoms of depression.

Causes and symptoms

The causes behind depression are complex and as of 2004 not fully understood. While an imbalance of certain neurotransmitters—the chemicals in the brain that transmit messages between nerve cells—is believed to be key to depression, external factors such as upbringing may be as important. For example, it is speculated that, if an individual is abused and neglected throughout childhood and adolescence , a pattern of low self-esteem and negative thinking may emerge. From that, a lifelong pattern of depression may follow.

Heredity seems to play a role in who develops depressive disorders. Individuals with major depression in their immediate family are up to three times more likely to have the disorder themselves. It would seem that biological and genetic factors may make certain individuals pre-disposed to depressive disorders, but environmental circumstances often may trigger the disorder as well.

External stressors and significant life changes such as chronic medical problems, death of a loved one, or divorce or estrangement of parents also can result in a form of depression known as adjustment disorder. Although periods of adjustment disorder usually resolve themselves, occasionally they may evolve into a major depressive disorder.

Common red flags that children may be experiencing a depressive disorder include a sudden decline in grades and/or disinterest in schoolwork, avoidance of friends, loss of interest in extracurricular activities, and withdrawal from family.

Major depressive episode

Individuals experiencing a major depressive episode have a depressed mood and/or a diminished interest or pleasure in activities. Children experiencing a major depressive episode may appear or feel irritable rather than depressed. In addition, five or more of the following symptoms will occur on an almost daily basis for a period of at least two weeks:

- significant change in weight

- insomnia or hypersomnia (excessive sleep)

- psychomotor agitation or retardation

- fatigue or loss of energy

- feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt

- diminished ability to think or to concentrate, or indecisiveness

- recurrent thoughts of death or suicide and/or suicide attempts

Dysthymic disorder

Dysthymia commonly occurs in tandem with other psychiatric and physical conditions. Up to 70 percent of dysthymic patients have both dysthymic disorder and major depressive disorder, known as double depression. Substance abuse, panic disorders, personality disorders , social phobias , and other psychiatric conditions also are found in many dysthymic patients. Dysthymia is prevalent in patients with certain medical conditions, including multiple sclerosis, AIDS , hypothyroidism , chronic fatigue syndrome, diabetes, and post-cardiac transplantation. The connection between dysthymic disorder and these medical conditions is unclear, but it may be related to the way the medical condition and/or its pharmacological treatment affects neurotransmitters. Dysthymic disorder can lengthen or complicate the recovery of patients also suffering from medical conditions.

Along with an underlying feeling of depression, people with dysthymic disorder experience two or more of the following symptoms on an almost daily basis for a period for two or more years (most suffer for five years) or one year or more for children:

- under-eating or overeating

- insomnia or hypersomnia

- low energy or fatigue

- low self-esteem

- poor concentration or trouble making decisions

- feelings of hopelessness

When to call the doctor

Just like adults, children have days when they are feeling down. But if those blue or bad moods begin to interfere with schoolwork and daily living and start to increase in frequency, parents or caregivers need to seek help from their child's doctor. If a child or teen reveals at any time that they have had recent thoughts of self-injury or suicide, professional assistance from a mental healthcare provider or care facility should be sought immediately.

Diagnosis

In addition to an interview, a clinical inventory or scale such as the Child Depression Inventory (CDI) or the Child Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) may be used to assess a child's mental status and determine the presence of depressive symptoms. Tests may be administered in an outpatient or hospital setting by a pediatrician, general practitioner, social worker, psychiatrist, or psychologist.

Treatment

Major depressive and dysthymic disorders are typically treated with antidepressants or psychosocial therapy. Psychosocial therapy focuses on the personal and interpersonal issues behind depression, while antidepressant medication is prescribed to provide more immediate relief for the symptoms of the disorder. When used together correctly, therapy and antidepressants are a powerful treatment plan for the depressed child or adolescent.

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Zoloft) reduce depression by increasing levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter. Some clinicians prefer SSRIs for treatment of dysthymic disorder. Anxiety , diarrhea , drowsiness, headache , sweating, nausea , and insomnia all are possible side effects of SSRIs. As of 2004, fluoxetine was the only SSRI (and the only antidepressant drug) approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. However, physicians may prescribe other SSRIs in younger patients in an off-label use of these drugs.

In 2004, fluoxetine and nine other antidepressant drugs came under scrutiny when the FDA issued a public health advisory and announced it was requesting the addition of a warning statement in drug labeling that outlined the possibility of worsening depression and increased suicide risk. These developments were the result of several clinical studies that found that some children taking these antidepressants had an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and actions. The FDA announced at the time that the agency would embark on a more extensive analysis of the data from these clinical trials and decide if further regulatory action was necessary.

Older classes of antidepressant drugs—(tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), heterocyclics, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)—do not have any substantial demonstrated effectiveness in pediatric populations and have potentially serious side effects that make them undesirable for child and adolescent use.

For severe depression that does not respond well to antidepressant, mood stabilizer drugs (e.g., lithium, carbamazepine, valproic acid) may be recommended.

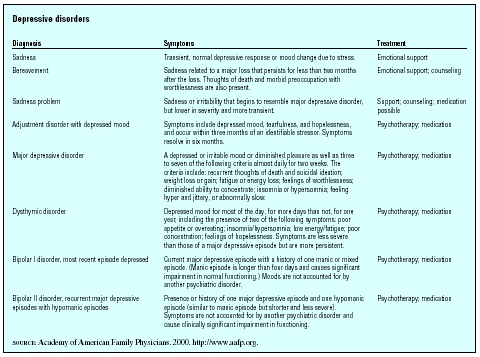

| Diagnosis | Symptoms | Treatment |

| SOURCE : Academy of American Family Physicians. 2000. http://www.aafp.org. | ||

| Sadness | Transient, normal depressive response or mood change due to stress. | Emotional support |

| Bereavement | Sadness related to a major loss that persists for less than two months after the loss. Thoughts of death and morbid preoccupation with worthlessness are also present. | Emotional support; counseling |

| Sadness problem | Sadness or irritability that begins to resemble major depressive disorder, but lower in severity and more transient. | Support; counseling; medication possible |

| Adjustment disorder with depressed mood | Symptoms include depressed mood, tearfulness, and hopelessness, and occur within three months of an identifiable stressor. Symptoms resolve in six months. | Psychotherapy; medication |

| Major depressive disorder | A depressed or irritable mood or diminished pleasure as well as three to seven of the following criteria almost daily for two weeks. The criteria include: recurrent thoughts of death and suicidal ideation; weight loss or gain; fatigue or energy loss; feelings of worthlessness; diminished ability to concentrate; insomnia or hypersomnia; feeling hyper and jittery, or abnormally slow. | Psychotherapy; medication |

| Dysthymic disorder | Depressed mood for most of the day, for more days than not, for one year, including the presence of two of the following symptoms: poor appetite or overeating; insomnia/hypersomnia; low energy/fatigue; poor concentration; feelings of hopelessness. Symptoms are less severe than those of a major depressive episode but are more persistent. | Psychotherapy; medication |

| Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed | Current major depressive episode with a history of one manic or mixed episode. (Manic episode is longer than four days and causes significant impairment in normal functioning.) Moods are not accounted for by another psychiatric disorder. | Psychotherapy; medication |

| Bipolar II disorder, recurrent major depressive episodes with hypomanic episodes | Presence or history of one major depressive episode and one hypomanic episode (similar to manic episode but shorter and less severe). Symptoms are not accounted for by another psychiatric disorder and cause clinically significant impairment in functioning. | Psychotherapy; medication |

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, involves analyzing a child's life to bring to light possible contributing causes of the present depression. During treatment, the therapist helps the patient to become aware of his or her thinking patterns and how they came to be, and works with them to develop healthy problem solving and copying skills. In very young patients, a therapist may use toys , games, and dolls as a vehicle for helping a child express her emotions. This type of therapy, sometimes referred to as play therapy, is useful in children who may not have the developmental capacity or language skills to express the thoughts and feelings behind their depression.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy assumes that the patient's faulty thinking is causing the current depression and focuses on changing the depressed patient's thought patterns and perceptions. The therapist helps the patient identify negative or distorted thought patterns and the emotions and behavior that accompany them and then retrains the depressed individual to recognize the thinking and react differently to it.

Electroconvulsant therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is only considered after all therapy and pharmaceutical treatment options have been unsuccessful, and even then it is a treatment of last resort, typically employed when a patient has become catatonic, suicidal, or psychotic as well as depressed.

The treatment consists of a series of electrical pulses that move into the brain through electrodes on the patient's head. ECT is given under anesthesia, and patients are administered a muscle relaxant to prevent convulsions. Although the exact mechanisms behind the success of ECT therapy are not known, it is believed that the electrical current modifies the electrochemical processes of the brain, consequently relieving depression. Headaches, muscle soreness, nausea, and confusion are possible side effects immediately following an ECT procedure. Memory loss, typically transient, also has been reported in ECT patients.

Alternative treatment

St. John's wort ( Hypericum perforatum ) isused throughout Europe to treat mild depressive symptoms. Unlike traditional prescription antidepressants, this herbal antidepressant has few reported side effects. Despite uncertainty concerning its effectiveness, a 2003 report said acceptance of the treatment continues to increase. A poll showed that about 41 percent of 15,000 science professionals in 62 countries said they would use St. John's wort for mild to moderate depression. The usual adult dose is 300 mg three times daily and may be lowered for children and adolescents.

In several small studies, S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM, SAMe) was shown to be more effective than placebo and equally effective as tricyclic antidepressants in treating depression. In 2003, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services team reviewed 100 clinical trials on SAMe and concluded that it worked as well as many prescription medications without side effects of stomach upset.

Parents and caregivers of children who suffer from depression should consult their child's physician before administering any herb or dietary supplement. Some supplements can interfere with the action of other prescription and over-the-counter medications. In addition, some supplements may not be appropriate for use in children with certain medical conditions.

A report from Great Britain published in 2003 emphasized that more physicians should encourage alternative treatments such as behavioral and self-help programs, supervised exercise programs, and watchful waiting before subscribing antidepressant medications for mild depression.

Nutritional concerns

Poor nutrition , especially eating habits that lead to overweight or obesity in children, can also contribute to depression. A 2003 study in the journal Pediatrics found that children who are substantially overweight for long periods of time are more likely to suffer from depression. Whether the depression causes the weight problem or the weight issue triggers the depression was not completely clear.

Prognosis

Untreated or improperly treated depression is the number one cause of suicide in the United States. Proper treatment relieves symptoms in 80 to 90 percent of depressed patients. After each major depressive episode, the risk of recurrence climbs significantly: 50 percent after one episode, 70 percent after two episodes, and 90 percent after three episodes. For this reason, patients need to be aware of the symptoms of recurring depression and may require long-term maintenance treatment of antidepressants and/or therapy.

Prevention

Good nutrition, proper sleep, exercise, and family support are all important to a healthy mental state, particularly in children. Extended maintenance treatment with antidepressants may be required in some patients to prevent relapse. Early intervention for children with depression can be effective in avoiding the development of more severe psychological problems later in life.

Parental concerns

Children who are diagnosed with depression should be reassured that the condition is quite common and that it is due to factors beyond their control (i.e., genetics, neurochemical imbalance) rather than any fault of the child. For those children and teens who feel stigmatized or self-conscious about their depression, arranging psychotherapy sessions outside school hours may lessen their burden. Any child prescribed antidepressants should be carefully monitored for any sign of side effects, and these should be reported to their physician when they do occur. A dosage adjustment or medication change may be warranted if side effects are disruptive or potentially dangerous.

KEY TERMS

Hypersomnia —An abnormal increase of 25% or more in time spent sleeping. Individuals with hypersomnia usually have excessive daytime sleepiness.

Neurotransmitter —A chemical messenger that transmits an impulse from one nerve cell to the next.

Psychomotor agitation —Disturbed physical and mental processes (e.g., fidgeting, wringing of hands, racing thoughts); a symptom of major depressive disorder.

Psychomotor retardation —Slowed mental and physical processes characteristic of a bipolar depressive episode.

See also Bipolar disorder .

Resources

BOOKS

Barnard, Martha Underwood. Helping Your Depressed Child. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 2003.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ,4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2000.

Shaffer, David, and Bruce Waslick, eds. The Many Faces of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

PERIODICALS

"A Natural Mood-Booster that Really Works: A Group of Noted Researchers Found that the Supplement SAMe Works as Well as Antidepressant Drugs." Natural Health (July 2003): 22.

"FDA Approves Once-daily Supplement." Biotech Week (September 24, 2003): 6.

"Try Alternatives Before Using Antidepressants." GP (September 29, 2003): 12.

Vitiello, B., and S. Swedo. "Antidepressant Medications in Children." New England Journal of Medicine 350, no. 15 (April 8, 2003): 1489–91.

ORGANIZATIONS

American Psychiatric Association. 1000 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1825, Arlington, VA 22209. Web site: http://www.psych.org.

American Psychological Association (APA). 750 First St. NE, Washington, DC 20002–4242. Web site: http://www.apa.org.

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA). 730 N. Franklin St., Suite 501, Chicago, IL 60610. Web site: http://www.dbsalliance.org.

National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI). Colonial Place Three, 2107 Wilson Blvd., Ste. 300, Arlington, VA 22201–3042. Web site: http://www.nami.org.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Office of Communications, 6001 Executive Blvd., Room 8184, MSC 9663, Bethesda, MD 20892–9663. Web site: http://www.nimh.nih.gov.

WEB SITES

Larsen, Willow. "The Obesity-Depression Link." Psychology Today (May 30, 2003). Available online at http://www.psychologytoday.com/htdocs/prod/ptoarticle/pto-20030527-000010.asp (accessed December 26, 2004).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Antidepressant [links]." Available online at http://www.fda.gov (accessed December 26, 2004).

Paula Ford-Martin Teresa Odle

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: