Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

Definition

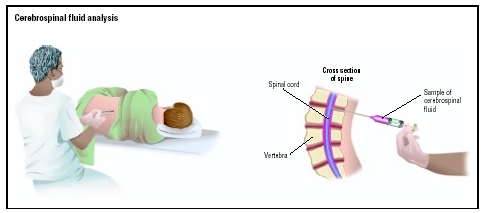

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is a set of laboratory tests that examine a sample of the fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord. This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of plasma. Plasma is the liquid portion of blood. CSF is clear and colorless. It contains glucose, electrolytes, amino acids, and other small molecules found in plasma, but it has very little protein and few cells. CSF protects the central nervous system from injury, cushions it from the surrounding bone structure, provides it with nutrients, and removes waste products by returning them to the blood.

CSF is withdrawn from the subarachnoid space through a needle by a procedure called a lumbar puncture or spinal tap. CSF analysis includes tests in clinical chemistry, hematology, immunology, and microbiology. Usually three or four tubes are collected. The first tube is used for chemical and/or serological analysis, and the last two tubes are used for hematology and microbiology tests. This method reduces the chances of a falsely elevated white cell count caused by a traumatic tap (bleeding into the subarachnoid space at the puncture site), and contamination of the bacterial culture by skin germs or flora.

Purpose

The purpose of a CSF analysis is to diagnose medical disorders that affect the central nervous system. Some of these conditions are as follows:

- meningitis and encephalitis , which may be viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections

- metastatic tumors (e.g., leukemia) and central nervous system tumors that shed cells into the CSF

- syphilis, a sexually transmitted bacterial disease

- bleeding (hemorrhaging) in the brain and spinal cord

- Guillain-Barré, a demyelinating disease involving peripheral sensory and motor nerves

Routine examination of CSF includes visual observation of color and clarity and tests for glucose, protein, lactate, lactate dehydrogenase, red blood cell count, white blood cell count with differential, syphilis serology (testing for antibodies indicative of syphilis), Gram stain, and bacterial culture. Further tests may need to be performed depending upon the results of initial tests and the presumptive diagnosis.

GROSS EXAMINATION Color and clarity are important diagnostic characteristics of CSF. Straw, pink, yellow, or amber pigments (xanthochromia) are abnormal and indicate the presence of bilirubin, hemoglobin, red blood cells, or increased protein. Turbidity (suspended particles) indicates an increased number of cells. Gross examination is an important aid to differentiating a subarachnoid hemorrhage from a traumatic tap. The latter is often associated with sequential clearing of CSF as it is collected; streaks of blood in an otherwise clear fluid; or a sample that clots.

GLUCOSE CSF glucose is normally approximately two-thirds of the fasting plasma glucose. A glucose level below 40 mg/dL is significant and occurs in bacterial and fungal meningitis and in malignancy.

PROTEIN Total protein levels in CSF are normally very low, and albumin makes up approximately two-thirds of the total. High levels are seen in many conditions, including bacterial and fungal meningitis, tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and traumatic tap.

LACTATE The CSF lactate is used mainly to help differentiate bacterial and fungal meningitis, which cause increased lactate, from viral meningitis, which does not.

LACTATE DEHYDROGENASE This enzyme is elevated in bacterial and fungal meningitis, malignancy, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

WHITE BLOOD CELL (WBC) COUNT The number of white blood cells in CSF is very low, usually necessitating a manual WBC count. An increase in WBCs may occur in many conditions, including infection (viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic), allergy, leukemia, hemorrhage, traumatic tap, encephalitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The WBC differential helps to distinguish many of these causes. For example, viral infection is usually associated with an increase in lymphocytes, while bacterial and fungal infections are associated with an increase in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils). The differential may also reveal eosinophils associated with allergy and ventricular shunts; macrophages with ingested bacteria (indicating meningitis), RBCs (indicating hemorrhage), or lipids (indicating possible cerebral infarction); blasts (immature cells) that indicate leukemia; and malignant cells characteristic of the tissue of origin. About 50 percent of metastatic cancers that infiltrate the central nervous system and about 10 percent of central nervous system tumors will shed cells into the CSF.

RED BLOOD CELL (RBC) COUNT While not normally found in CSF, RBCs will appear whenever bleeding has occurred. Red cells in CSF signal subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke , or traumatic tap. Since white cells may enter the CSF in response to local infection, inflammation, or bleeding, the RBC count is used to correct the WBC count so that it reflects conditions other than hemorrhage or a traumatic tap. This is accomplished by counting RBCs and WBCs in both blood and CSF. The ratio of RBCs in CSF to blood is multiplied by the blood WBC count. This value is subtracted from the CSF WBC count to eliminate WBCs derived from hemorrhage or traumatic tap.

GRAM STAIN The Gram stain is performed on a sediment of the CSF and is positive in at least 60 percent of cases of bacterial meningitis. Culture is performed for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. In addition, other stains (e.g. the acid-fast stain for Mycobacterium tuberculosis , fungal culture, and rapid identification tests (tests for bacterial and fungal antigens) may be performed routinely.

SYPHILIS SEROLOGY Syphilis serology involves testing for antibodies that indicate neurosyphilis. The fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) test is often used and is positive in persons with active and treated syphilis. The test is used in conjunction with the VDRL test for nontreponemal antibodies, which is

Description

Lumbar puncture is performed by inserting the needle between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5). This location is used because the spinal cord stops near L2, and a needle introduced below this level will miss the cord. In rare instances, such as a spinal fluid blockage in the middle of the back, a physician may perform a spinal tap in the cervical spine.

Precautions

In some circumstances, a lumbar puncture to withdraw a small amount of CSF for analysis may lead to serious complications. Lumbar punctures should be performed only with extreme caution and only if the benefits are thought to outweigh the risks. In people who have bleeding disorders, lumbar puncture can cause hemorrhage that can compress the spinal cord. If there is increased spinal column pressure, as may occur with a brain tumor and other conditions, removal of CSF can cause the brain to herniate, compressing the brain stem and other vital structures and leading to irreversible brain damage or death. Meningitis may be caused by bacteria introduced during the puncture. For this reason, aseptic technique must be followed strictly, and a lumbar puncture should never be performed at the site of a localized skin lesion.

Specimens should be handled with caution to avoid contamination with skin flora. They should be refrigerated if analysis cannot be performed immediately.

Aftercare

After the procedure, the site of the puncture is covered with a sterile bandage. The patient should remain lying for four to six hours after the lumbar puncture. Vital signs should be monitored every 15 minutes for four hours, then every 30 minutes for another four hours. The puncture site should be observed for signs of weeping or swelling for 24 hours. The neurological status of the patient should also be evaluated for such symptoms as numbness and/or tingling in the lower extremities.

Risks

The most common side effect after the removal of CSF is a headache . This occurs in up to 40 percent of children. It is caused by a decreased CSF pressure related to a small leak of CSF through the puncture site. These headaches usually are a dull pain , although some people report a throbbing sensation. A stiff neck and nausea may accompany the headache. Lumbar puncture headaches typically begin within two days after the procedure and persist from a few days to several weeks or months.

Normal results

The normal results include the following:

- gross appearance: normal CSF, clear and colorless

- CSF opening pressure: in children older than six to eight years, 90–180 mm H 2 O; in infants and younger children, 10–100 mm H 2 O

- specific gravity: 1.006–1.009

- glucose: 40–80 mg/dL

- total protein: 15–45 mg/dL

- LD: 1/10 of serum level

- lactate: less than 35 mg/dL

- leukocytes (white blood cells): 0–6/microL (adults and children); up to 19/microL in infants; up to 30/microL (newborns)

- differential: 60–80 percent lymphocytes; up to 30 percent monocytes and macrophages; other cells 2 percent or less. Monocytes and macrophages are somewhat higher in neonates, and make up as much as 80 percent or more, with only 20 percent or less being lymphocytes.

- Gram stain: negative

- culture: sterile

- syphilis serology: negative

- red blood cell count: normally, none unless the needle passes though a blood vessel on route to the CSF

Parental concerns

If the child is anxious or uncooperative, a short-acting sedative may be given. Patients receive a local anesthetic to minimize any pain in the lower back from inserting the needle.

When to call the doctor

If the child does not respond to the parents, if the puncture site continues to leak a watery fluid, or the puncture site appears red and swollen, or has other signs of infection, then the doctor should be notified.

KEY TERMS

Demyelination —Disruption or destruction of the myelin sheath, leaving a bare nerve. It results in a slowing or stopping of the impulses that travel along that nerve.

Encephalitis —Inflammation of the brain, usually caused by a virus. The inflammation may interfere with normal brain function and may cause seizures, sleepiness, confusion, personality changes, weakness in one or more parts of the body, and even coma.

Guillain-Barré syndrome —Progressive and usually reversible paralysis or weakness of multiple muscles usually starting in the lower extremities and often ascending to the muscles involved in respiration. The syndrome is due to inflammation and loss of the myelin covering of the nerve fibers, often associated with an acute infection. Also called acute idiopathic polyneuritis.

Meningitis —An infection or inflammation of the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. It is usually caused by bacteria or a virus.

Multiple sclerosis —A progressive, autoimmune disease of the central nervous system characterized by damage to the myelin sheath that covers nerves. The disease, which causes progressive paralysis, is marked by periods of exacerbation and remission.

Spinal canal —The opening that runs through the center of the spinal column. The spinal cord passes through the spinal canal. Also called the vertebral canal.

Subarachnoid —Referring to the space underneath the arachnoid membrane, the middle of the three membranes that sheath the spinal cord and brain.

Treponeme —A term used to refer to any member of the genus Treponema , which is an anaerobic bacteria consisting of cells, 3–8 micrometers in length, with acute, regular, or irregular spirals and no obvious protoplasmic structure.

Vertebrae —Singular, vertebra. The individual bones of the spinal column that are stacked on top of each other. There is a hole in the center of each bone, through which the spinal cord passes.

Resources

BOOKS

Braunwald, Eugene, ed., et al. "Approach to the Patient with Neurologic Disease." In Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine , 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

Henry, J. B. Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods , 20th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001.

Kee, Joyce LeFever. Handbook of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests , 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001.

Smith, Gregory P., and Carl R. Kieldsberg. Cerebrospinal, Synovial, and Serous Body Fluids. Philadelphia: Saunders Co., 2001.

Wallach, Jacques. Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests , 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkens, 2000.

ORGANIZATIONS

National Institutes of Health. 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892. Web site: http://www.nih.gov.

Mark A. Best

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: