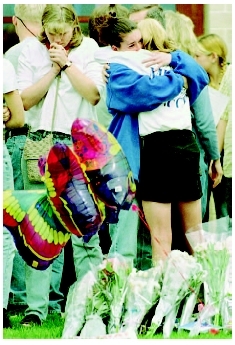

Death and mourning

Definition

Mourning is the grieving process an individual experiences in response to the loss (often through death) of someone.

Description

Almost every child or adolescent faces the death of someone close (a relative, friend, or even a pet) at some point in his or her life. In fact, it is estimated that about 6 percent of children under age 15, or about three of every 50 children, will lose a parent. Though this figure is low compared to 25 percent at the turn of the twentieth century, children in the twenty-first century are more likely to experience more types of violent and catastrophic death, such as in wars, natural disasters, and homicides. Children experience deaths of their peers through suicide , acts of violence in school or on the street, and in terminal illness.

In 1900, children experienced death firsthand, seeing a loved one die on the farm or in the home. Then, two world wars came and children experienced death in the remote events of far off places. By the 1950s, though some children did experience the death of a loved one in the Korean War, these were few. Death became an abstraction, something children only read about or experienced in a movie or television. The Vietnam War and racial unrest during the civil rights era connected death as reported by newspapers and television to events occurring U.S. city streets. By the last two decades of the twentieth century, death came knocking on the schoolhouse door as children brought weapons and shot other children. Drive-by shootings became more frequent in some neighborhoods. With the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, children began to see widespread death in a very personal way.

Children experience grief or mourning in very different ways than adults do. That is why over 160 bereavement centers have opened across the United States to help children mourn in ways that are appropriate to their age and developmental stage. These centers also allow children to participate in their own mourning rituals, which can be a comfort to children and a healthy way to move on. Unlike in some religious organizations, children are allowed to express anger as well as sadness about the death of their loved ones. They are encouraged to remember and create tangibles, such as paintings, stories, and even quilts, to remind them of the deceased.

Parents, caregivers, and teachers can provide support and minimize fear by answering honestly a child's questions about death. Encouraging communication helps the child through the essential grieving period. At one time, well-meaning adults felt that it was in the child's best interests to avoid discussing death. However, research has shown that children cope more successfully with a death if they feel included in the group that has experienced the loss and share in grieving and mourning.

When listening to a child's observations about death, adults must keep an open mind. A child may respond to the death of a grandmother, who used to make cupcakes for her, by observing that there will be no more cupcakes for dessert. This response could be interpreted as selfish, but it is in fact an expression of the child's loss in her own, very personal, terms. When a child learns of the accidental death of a playmate, he may ask to go out to play . This too may be an expression of the loss, as the child might want to remember his friend by engaging in the activity the two of them shared. The child's response to loss can be misunderstood by adults, especially by those who are also grieving. By passing judgment on the child's reactions, adults undermine the child's feelings and make the loss even more difficult for the child to handle.

For most people, deeply felt grief and loss are felt for about a week, followed by sorrow which can last two years or longer. In the days, weeks, and months that follow a death, adults should refrain from criticizing or reacting negatively to the child's feelings. When the child seems to repeat the same questions over and over, the same answers, as open and honest as possible, must be repeated patiently. Young children may express concern, either directly or through behavior, about being abandoned or neglected, or they may fear they have in some way caused the death. Changes in appetite, complaints of feeling sick, and changes in activity patterns can be indications that the child is worried or anxious. Adults can help a child deal with these feelings by acknowledging them and by reassuring the child that he will still be cared for and that no one can cause a death by thoughts and feelings.

When a death is unanticipated, as in a case of accident or violence, children may grieve longer and more intensely. Sad feelings may resurface over the years when the child experiences the loss anew, such as on holidays or other occasions. When a parent is deeply affected by the death of a loved person, the child may need the steady support of another adult. Books about illness and death can also be helpful. Adults should review the books in advance or ask a librarian, teacher, or counselor for advice. Issues of concern include age-appropriateness, situation-appropriateness, and religious point of view.

Children mourn a bit at a time, returning to their grief anew at different stages. Understanding a child's developmental stages helps parents, teachers, and caregivers provide appropriate responses and support for the child.

Toddlerhood and preschool age

By the time a child is about two and a half or three, the child is able to acknowledge that a death has occurred but will not really understand the reality of death. The child may echo the parents' words but may also express their lack of understanding. This is less denial than it is the inability to understand the concept of death. If a child has experienced the death of a family pet and understands that the dog or cat will not come back, the child is more likely to understand that the person who dies will not come back either.

Children between two and five years of age will often be restless, have sleep disturbances, or frightening dreams. They will sometimes revert to behaviors they had at a younger age, such as wetting the bed or thumb sucking . Because children of this developmental stage do not fully understand the concept of death, they may blame themselves, thinking that if only they had been good enough, their loved one would not have died.

Parents and other adults need to offer comfort in simple but honest words and in physical contact. They need to make sure the child's routine remains intact to preserve a sense of security in a loving environment. Caregivers can draw pictures of the loved one or read books about mourning so the child can feel that they are not alone. Even children of this age can participate in funerals or other death rituals.

School age

By the age of six, children begin to understand that death is the cessation of bodily functions and that it is permanent. They show a morbid curiosity about death. They may talk about the details of death repeatedly. They want to know what happens physically and spiritually. Children of this age may also begin to acknowledge the universality of death, that it happens to everyone. But they may find it difficult to believe that it could ever happen to them.

Around this age, children are capable of taking part in rituals of death, such as visits with the deceased's family, the wake, and the funeral or memorial service. Prior to participating in a visit or funeral, it is helpful to prepare the child for the experience by explaining the purpose of the visit, how long it will last, and what the child will experience there. If a child expresses reluctance to participate in any aspect of the rituals of death, adults should accept the child's feelings and not exert pressure. Children look to adults and their peers for role models of how to conduct themselves at these events.

School-aged children can understand what death means, but they may be so overwhelmed that they act as if nothing has happened. Unexpressed feelings may surface as physical symptoms, such as stomachache, headache , and unusual complaint of tiredness. Behavior may also change, demonstrated by reluctance to go to school, daydreaming in class, or a decline in academic performance. Children of this age usually need extra time for physical activity. Even a short walk or a turn at the playground can help them work off some of the physical tensions connected with mourning.

Children both grieve alone and share their grief with others. Families can take a number of actions to support emotional healing, such as openly acknowledging the death, letting children participate in the rituals, and maintaining familiar routines such as school and bedtime activities. Parents should also let children witness their own adult grief. Rather than avoiding any mention of the deceased, it may help to display a photograph in a prominent place as a way of letting family members maintain memories. The visual reminder provides a way to help the child understand that it is okay to talk about the person who died.

For some children, the threat of being alone is central. One of their first questions is usually, "Who is going to take care of me?" Caregivers need to reassure the child that he or she is still loved and will be cared for.

Some older children begin to understand that death can happen to anyone, especially if a child their own age dies. The child may also worry that he or she may die at any time. This is especially a problem when the child's peer dies suddenly in an accident or after a long illness. Questions like "Will I die, too?" need reassuring answers.

Adolescence

Teenagers understand more as an adult does, but they may find it even more difficult than younger children to deal with their sorrow. Behavior problems, dropping out of school, physical complaints such as headache or chest pain , sexual promiscuity, and even suicide attempts may result from their feelings of pain and loss. Often, teenagers are reluctant to talk to adults who could help them through their grief.

The death of a peer, even someone they hardly knew, affects adolescents differently than the death of an older person. They must cope not only with the shock of life's unpredictability, but their own mortality.

Some adolescents may feel anger and want to rage at the world for letting death take a loved one. Research has shown that in the majority of cases adolescents in juvenile facilities have lost someone close to them.

Adolescents can also feel very vulnerable. Some express the need to feel like a child again, to be taken care of and protected, to feel secure in a safe world.

Common problems

Nighttime is particularly problematic since the child is now able to remember his or her loss without other distractions intervening. The child may also feel abandoned and alone. Many children will want to sleep with a parent or a sibling. Others request that a light be left on, even if they have long since stopped needing a nightlight.

Many children will also revert to a previous developmental stage. Some children will wet the bed. Others will request permission to sleep with a stuffed animal or return to sucking their thumbs. Some of these behaviors are comfort actions. They seek the security of the earlier developmental stage.

Older children and adolescents may express their bottled up anger through aggression toward other children. They may also turn that unresolved anger inward, becoming depressed or adopting a dark, gloomy lifestyle. Some adolescents may participate in risk-taking behaviors or want to do everything because they are worried that they may not have time to do everything before some random act kills them. Other children and adolescents may mutilate themselves or get body piercings or tattoos. (It should be noted that piercing and tattoos are

Parental concerns

Parents need to help their children work through their grief, not get around it or avoid it. Parents should never minimize their child's grief. It is as individual as any adult's. Parents and other caregivers need to be available to listen as children express their grief in their own ways. This means that parents should seek counseling themselves if their own grief gets in the way of helping their children move through the grieving process.

Grieving children need their friends' support as much as adults do. Parents should make sure that children are allowed to phone their friends or play with them during the grieving process. Children will often express their sadness to friends much more easily than to their parents or other adults.

In addition, funerals and other death rituals are important to children as well as adults. These gatherings allow the bereaved to express their sorrow, remember those they have lost, and receive and offer support from a community of friends and relatives. Death rituals often are the moments when the death of a loved one becomes real and not just tragic news. The bereaved often need to see the body of the deceased or participate in some activity that expresses the letting go of their dead loved one's presence in this life. Some families release balloons after a funeral; others light candles and let them burn down; both activities express the release of the deceased from life to death. Many of these activities coincide with religious beliefs and customs. Children who participate in a funeral by reading a poem or offering a gift are often better able to cope with their loss.

When to call the doctor

About one third of grieving children may need to seek professional counseling or therapy of some kind. This can be in individual sessions or in a group. It can also come from religious sources. Behaviors that warrant grief counseling or therapy are unresolved anger and hostility, not expressing grief at all or minimally, or depression or anxiety that interferes with daily activities that lasts for weeks or months.

KEY TERMS

Bereavement —The emotional experience of loss after the death of a friend or relative.

Grief reaction —The normal depression felt after a traumatic major life occurrence such as the loss of a loved one.

Mourn —To express grief or sorrow, usually for a death.

Resources

BOOKS FOR ADULTS

Ashenburg, Katherine. The Mourner's Dance: What We Do When People Die. New York: North Point Press, 2003.

Doka, Kenneth J. Living with Grief: Children, Adolescents, and Loss. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2000.

Huntley, Theresa. Helping Children Grieve: When Someone They Love Dies. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2002.

BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

Joosse, Barbara M. Ghost Wings. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 2001.

Parker, Marjorie Blain. Jasper's Day. Tonawanda, NY: Kids Can Press, 2002.

PERIODICALS

Dickinson, Amy. "Kids and Funerals: Rather than Protect Our Children from Grief, We Should Encourage Them to Experience It." Time 155 (March 6, 2000): 79.

Kelly, Katy. "After a Loss, Kids Need to Mourn and Be Reassured." U.S. News & World Report 130 (January 8, 2001): 51.

Janie Franz

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: