Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Definition

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a procedure to support and maintain breathing and circulation for an infant, child, or adolescent who has stopped breathing (respiratory arrest) and/or whose heart has stopped (cardiac arrest).

Purpose

CPR is performed to restore and maintain breathing and circulation and to provide oxygen and blood flow to the heart, brain, and other vital organs. CPR can be performed by trained laypeople or healthcare professionals on infants, children, adolescents, and adults. CPR should be performed if an infant, child, or adolescent is unconscious and not breathing. Respiratory and cardiac arrest can be caused by allergic reactions, an ineffective heartbeat, asphyxiation, breathing passages that are blocked, choking , drowning, drug reactions or overdoses, electric shock, exposure to cold, severe shock, or trauma. In newborns, the most common cause of cardiopulmonary arrest is respiratory failure caused by sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), airway obstruction (usually from inhalation of a foreign body), sepsis, neurologic disease, or drowning. Cardiac arrest in children over one year of age is most commonly caused by shock and/or respiratory failure resulting from an accident or injury.

Description

CPR is part of the emergency cardiac care system designed to save lives. Many deaths can be prevented by prompt recognition of cardiopulmonary arrest and notification of the emergency medical system (EMS), followed by early CPR, defibrillation (which delivers a brief electric shock to the heart in attempt to get the heart to beat normally), and advanced cardiac life support measures. When performed by a layperson, CPR is designed to support and maintain breathing and circulation until emergency medical personnel arrive and take over. When performed by healthcare personnel, it is used in conjunction with other basic and advanced life support measures.

CPR must be performed within four to six minutes after cessation of breathing to prevent brain damage or death. CPR consists of rescue breathing, which delivers oxygen to the victim's lungs, and external chest compressions, which help circulate blood through the heart to vital organs.

CPR technique differs for infants, children, and adolescents. The American Heart Association and the American Red Cross, the two organizations that provide CPR training and guidelines, distinguish infants, children, and adolescents for the purposes of CPR as follows:

- "Infant" includes neonates (those in the first 28 days of life) and extends to the age of one year.

- "Child" includes toddlers aged one year to children aged eight years.

- "Adult" includes children aged eight years and older.

Because infants and children under the age of eight have smaller upper and lower airways and faster heart rates than adults, CPR techniques are different for them than for older children and adults. Children and adolescents aged eight years and older have reached a body size that can be handled using adult CPR techniques and are thus classified as adults for delivery of CPR and life support. CPR is always begun after assessing the victim and contacting EMS.

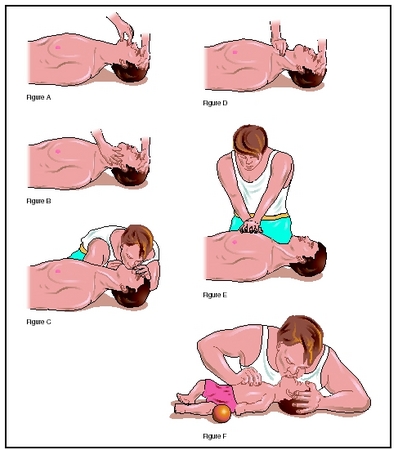

Performing CPR on an infant

For an infant, the rescuer opens the airway using a gentle head tilt/chin lift or jaw thrust, places their mouth over the infant's mouth and nose then delivers gentle breaths so that the infant's chest rises with each breath. Chest compressions are delivered by placing two fingers of one hand over the lower half of the infant's sternum slightly below the nipple line and pressing down about one half inch to one inch. Compressions are delivered at a rate of 100 times per minute, giving five chest compressions followed by one rescue breath in successive cycles.

Performing CPR on a child aged one to eight

For a child aged one to eight years, the compression rate is the same—five compressions and one rescue breath. Rescue breaths are delivered using a mouth-to-mouth seal, instead of mouth-to-mouth-and-nose. Chest compressions are delivered by placing the heel of one hand over the lower half of the sternum and depressing about one to one and one half inches per compression.

Performing CPR on a child aged eight and older

For a child aged eight years and older, and for larger children under age eight, two hands are used for compressions, with the heel of one hand on the lower half of the sternum and the heel of the other hand on top of that hand. The chest is compressed about one and one half to two inches per compression. Rescue breaths are delivered with a mouth-to-mouth seal. The compression rate is 80 to 100 per minute delivered in cycles of 15 compressions followed by two rescue breaths.

Preparation

Before administering CPR to an infant or child, laypeople should participate in hands-on training. More than 5 million Americans annually receive training in CPR through American Heart Association and American Red Cross courses. In addition to courses taught by instructors, the American Heart Association also has an interactive video called Learning System , which is available at more than 500 healthcare institutions. Both organizations teach CPR the same way, but they use different terms. CPR training should be retaken every two to three years to maintain skill level.

Precautions

CPR should not be performed based on the overview contained in this article. To prevent disease transmission during CPR, face masks and face shields are available to prevent direct contact during rescue breathing.

Aftercare

Emergency medical care is always necessary after CPR. Once a person's breathing and heartbeat have been is coming and talk positively until professionals arrive restored, the rescuer should make the person comfortable and stay there until emergency medical personnel arrive. The rescuer can continue to reassure the person that help and take over.

Risks

CPR can cause injury to a person's ribs, liver, lungs, and heart. However, these risks must be accepted if CPR is necessary to save the person's life.

Normal results

In many cases, successful CPR results in restoration of consciousness and life. Barring other injuries, a revived person usually returns to normal functions within a few hours of being revived.

Abnormal results include injuries incurred during CPR and lack of success with CPR. Possible sites for injuries include a person's ribs, liver, lungs, and heart. Partially successful CPR may result in brain damage. Unsuccessful CPR results in death.

Parental concerns

Because most cardiopulmonary arrest in infants and children occurs in or around the home and results from SIDS, trauma, drowning, choking, or poisoning , all parents and child caregivers should consider becoming trained in CPR. Training is available at local schools and community centers.

KEY TERMS

Cardiac arrest —Temporary or permanent cessation of the heartbeat.

Cardiopulmonary —Relating to the heart and lungs.

Defibrillation —A procedure to stop the type of irregular heart beat called ventricular fibrillation, usually by using electric shock.

Resuscitation —Bringing a person back to life or consciousness after he or she was apparently dead.

Ventricular fibrillation —An arrhythmia characterized by a very rapid, uncoordinated, ineffective series of contractions throughout the lower chambers of the heart. Unless stopped, these chaotic impulses are fatal.

Resources

BOOKS

Knoop, Kevin J., and Lawrence B. Stack. Atlas of Emergency Medicine , 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001.

Larmon, Baxter, et al. Basic Life Support Skills. Toronto, ON: Prentice Hall PTR, 2004.

PERIODICALS

Babbs, C. F., and V. Nadkarni. "Optimizing chest compression to rescue ventilation ratios during one-rescuer CPR by professionals and lay persons: children are not just little adults." Resuscitation 61, no. 2 (May 2004): 173–81

Kern, K. B., H. R. Halperin, and J. Field. "New guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care: changes in the management of cardiac arrest." Journal of the American Medical Association 285 (2001): 1267–69.

ORGANIZATIONS

American College of Emergency Physicians . PO Box 619911, Dallas, TX 75261–9911. Web site: http://www.acep.org.

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians. 142 E. Ontario Street, Suite 550, Chicago, IL 60611. Web site: http://www.acoep.org.

American Heart Association, National Center. 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231. Web site: http://www.americanheart.org.

WEB SITES

"Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation." American Heart Association , 2004. Available online at http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4479 (accessed October 29, 2004).

"CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care." American Heart Association , 2004. Available online at http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3011764 (accessed October 29, 2004).

"Infant First Aid for Choking and CPR: An Illustrated Guide." BabyCenter , 2004. Available online at http://www.babycenter.com/general/9298.html (accessed October 29, 2004).

Jennifer E. Sisk, MA

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: